Notable Elements

- Characteristic vernacular center-chimney timber-frame house that evolved in several stages [History & Frame]

- Freehand and stencil painted walls at second-storey chamber, ca. 1800-20 [Interior]

- Ambitious Georgian-style finishes in best rooms [Interior]

- Brick nogging and evidence of back plaster [Frame]

- Complex evolution of central chimney [Interior]

History

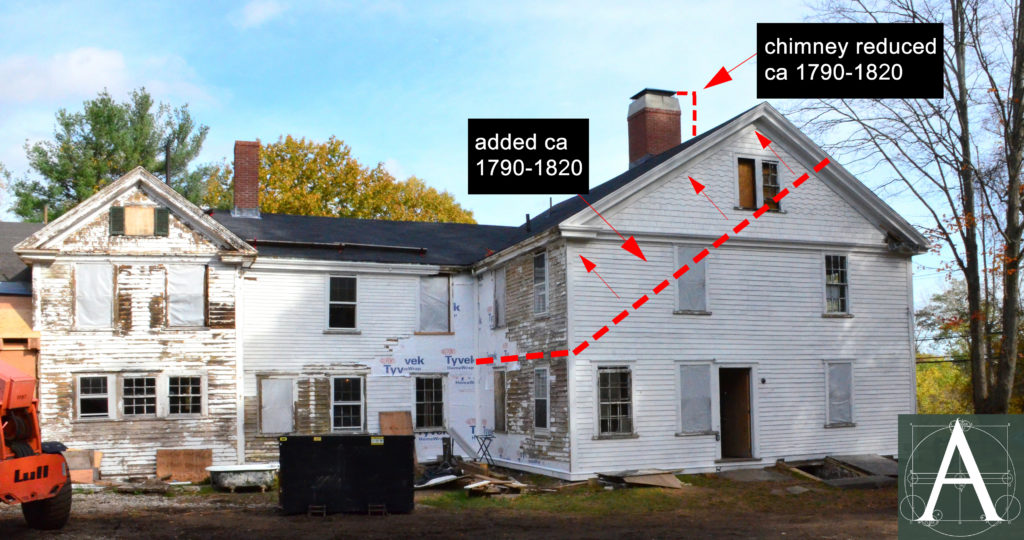

The Sarah Clayes House is an exceptionally fine example of a center-chimney, timber-frame house, the region’s most distinctive and widespread building type until the mid-nineteenth century. Although long believed by local historians to have been built in the 1690s for Peter Clayes shortly after he and his family fled the witchcraft trials in Salem, Massachusetts, the house contains no physical evidence to support such an early date. It seems likely that Clayes may have built his house elsewhere on the property, or that a portion of the present cellar may be related to an earlier house on the site. Based upon physical evidence and changes of ownership in the property, it is likely that the present house was constructed in the third quarter of the eighteenth century, perhaps in the 1760s or 1770s. The house may have been built for Clayes’s son-in-law John Parker (1703-83) during his ownership of the property (1734-1776), or, more likely, for Colonel David Brewer (1751-1834) who owned the property from 1776 until his death.

The Clayes House passed through a number of owners in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and remained occupied until the late 1990s, after which it was sold at a bank-ordered auction, but conveyance could not be made due to defective title. The building remained unoccupied and in limbo until 2015 when it was conveyed to Land Conservation Advocacy Trust for preservation.

Date

1770; 1790-1820; 1840-60; 1880s

Builder/Architect

Unknown

Building Type

Central-chimney timber-frame, single-family house

The house has a complicated evolution that exemplifies regional patterns of vernacular architecture during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As initially constructed, the house was composed of its main block, a simple rectangle with no wings or ells, enclosed by a lean-to roof (also known colloquially as a “saltbox” roof) which allowed full-height chambers at the second storey of the east (front) half of the building, while the western half of the second storey contained low rooms beneath the roof. A partial cellar existed under the northeast parlor and, perhaps also under the southeast parlor, but the area beneath the lean-to part of the house was merely an unexcavated crawl space. Around the turn-of-the-century (ca. 1790-1820), the lean-to roof was removed, a full second storey built in its place and the present roof was constructed, retaining some of the original roof framing at the east slope of the roof. A full cellar was excavated beneath the house. Simultaneously, or soon after this enlargement, a two-storey rear ell with a full cellar was added to the north end of the original house’s rear (west) wall. This ell was of timber-frame construction but had a brick end wall (west) into which was built a large working hearth, possibly containing set kettles that have since been removed.

Subsequent additions in the mid- and late nineteenth century extended the house back toward a barn, with space possibly used for resident farm hands between the old rear ell and barn. Documentation presented here focuses on the original house and first ell which contain the largest proportion of historic features and traditional building materials.

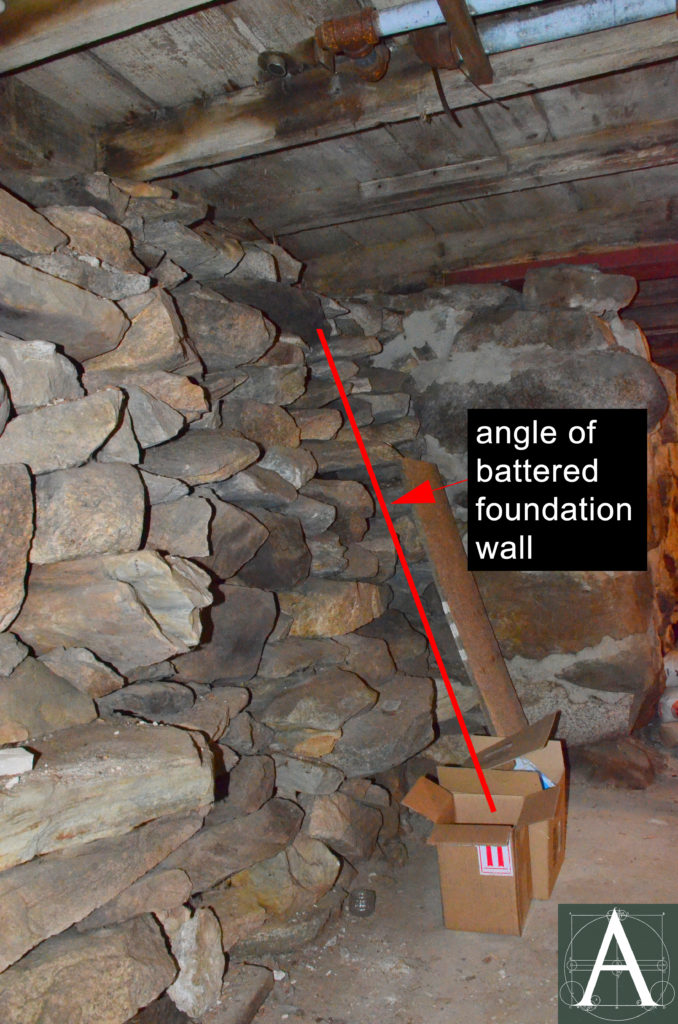

Foundation

Dry-laid granite fieldstone and rubble pointed with some lime mortar on the interior: The original cellar may only have consisted of one room under the northeast parlor, or possibly under the eastern half of the house with a crawl space beneath the lean-to portion of the main house. The cellar beneath the original house was probably fully excavated when the rear ell was constructed (ca. 1790-1820). It appears that west wall of the original cellar was left in position, its east face partially daubed with lime mortar, while its west face consists of exposed fieldstone battered inward from a wider base to a narrower top on which a timber rests. This practice of building cellar walls with a battered face set toward the dirt was common practice to provide greater resistance to the pressure of soil around the foundation.

Original foundation wall (ca. 1770) showing the exterior side with battered stonework originally designed to hold back soil, now exposed in the enlarged cellar

Frame

Oak timber frame: The original frame appears to be made nearly entirely of oak with squared posts, summers, girts, and plates that are cased or concealed by finish plaster. Where visible, none of these structural elements have moulded edges or whitewash coatings, indicating that they were probably never exposed to view. At the attic, the original frame of the east slope of the roof remains in position with a five-sided ridge pole (5” per face) into which rafters (3” x 4” to 3½” x 5” variable) were set with pinned mortise-and-tenon joints; front and rear rafters were directly aligned with each other. Joints preserve their assembly numbers, which include a mixed system of Roman numerals and marks that take the place of numerals. Numbers rise from south to north. Between numerals VIII and X is an irregular symbol that, presumably stands for IX. At each end, the original roof has angle braces joined into the ridge and end rafters; toward the center of the frame, additional angle braces existed at rafters on either side of the central chimney, which rose through the back (western) half of the ridge pole. A second numbering system for attic floor joists is partially visible on the top of the rear wall plate where small numerals II, III, and IIII mark the pockets for joists; the numbers rise from north to south, opposite to the direction of the rafter numbering system.

View of the original roof frame and ridge at the north gable, showing the added framing to raise the roof to its present height

View of timber-framer’s mark for the position of the ninth rafter from the south end of the original roof ridge

The two-storey rear ell was also heavily framed with a central summer beam (8” x 11”) extending its length at first and second storeys, 7” x 7” plates and a 7” x 9” chimney girt. 3” x 4” studs were set at variable intervals of 11” to 18” along the ell’s north and south walls. The second-storey walls preserve original studs and brick nogging composed of soft-fired, purpose-made nogging bricks (7½” to 8” in length x 4” in height and 2” in depth). Nogging bricks were laid in lime mortar approximately 1” inward from exterior sheathing and recessed ½” from the interior faces of the studs. Bricks were laid with staggered joints and their faces toward the room. Their shallow depth and one wythe’s thickness preclude bonding. These nogging bricks resemble those used in at the Samuel Dexter House (1791 – Charlestown, Massachusetts), now known as Memorial Hall, and at the rear ell (ca. 1795) of the Deacon Wrestling Brewster House in Kingston, Massachusetts. Brick nogging was used throughout much of New England starting in the seventeenth century and is associated with substantially built houses such as the Gedney House (1665 – Salem, Massachusetts). Its precise purpose is not clear, although it certainly provided some insulation and an opportunity to seal walls against drafts. It remained in use at least until the third-quarter of the nineteenth century, and partial installations of it are mentioned in the building specifications for the Hartley Lord House (1884 – Kennebunk, Maine) and the Jarvis Williams House (1869 – Boston, Massachusetts) as having the desirable property of “rat proofing” and “preventing vermin [from] rising” in the house.

North wall of the second storey of the rear ell showing brick nogging laid in lime mortar between studs

Close-up view showing the one inch gap between nogging and outside sheathing visible through the separation between a stud and nogging

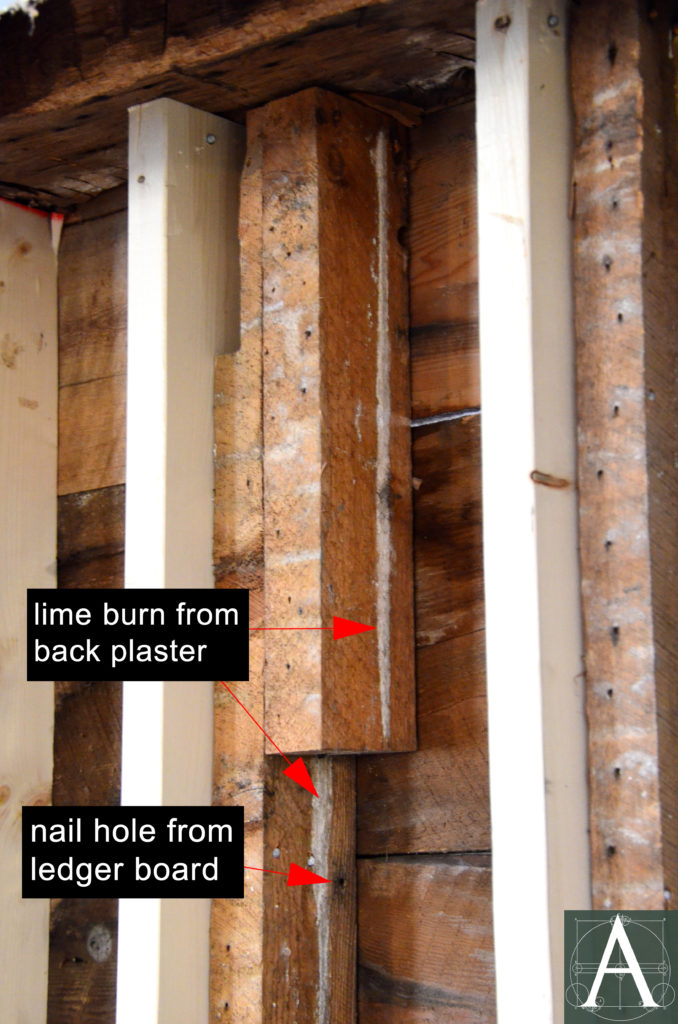

Alterations to the first storey of the rear ell caused the removal of the original nogging, perhaps as early as the 1840s-50s. At this time, original studs were removed, and new studs were nailed into place to create new doors and windows. The spaces between studs were back plastered, which also served to provide some insulation and to reduce drafts in the house. Scars of the back plastering show that ledge boards were nailed on the inside faces of the studs creating a cavity of approximately 1” depth when lath was nailed to the studs. A single layer, or brown coat, of lime plaster would have been applied; the lime burns that remain on the inside faces record the position of this layer of lime plaster. Recorded examples of back plastering tend to come from the nineteenth century, although that narrow range of dates may reflect lack of research on the topic. Associated with well-built, but not necessarily lavish houses, back plastering can be seen in buildings as diverse as the Levi Conant House (1844 – Cambridge, Massachusetts), an unnamed Greek-revival style house (1845-50 – Warren, Maine), the Hartley Lord House (1884 – Kennebunk, Maine), and the H. Addington Bruce House (1887 – Cambridge, Massachusetts).

North wall of the rear ell showing the marks left from back plaster, consisting of a white line burned into studs by lime plaster, and one of a series of nail holes by which ledger boards were attached to the sides of studs to support lath

Exterior

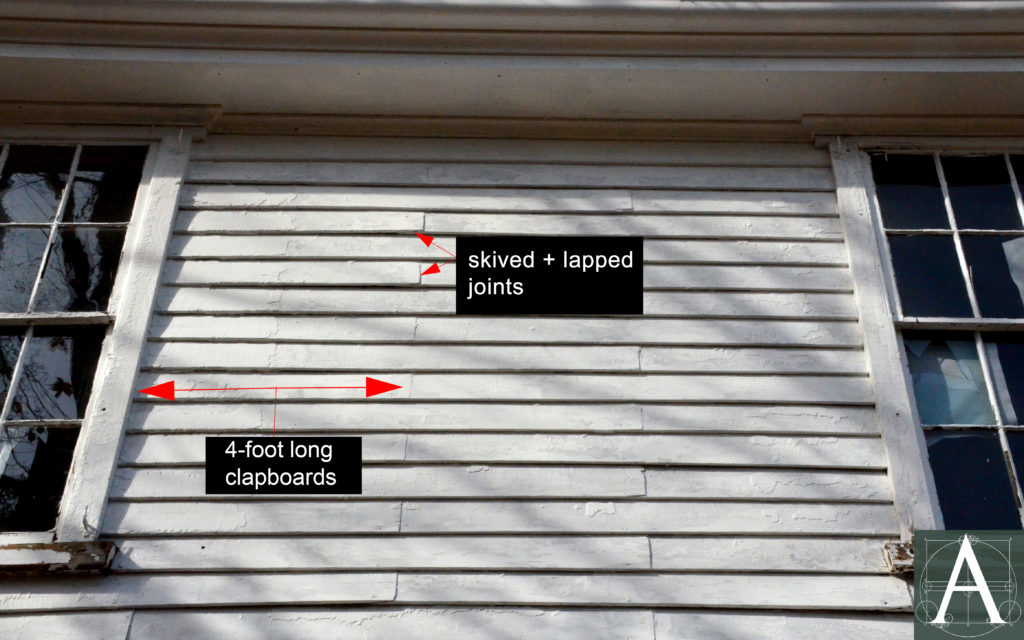

The exterior of the Clayes House preserves notable original Georgian-style detail as well as a well-preserved Greek Revival-style entry. The principal elevations of the original house (north, east, and south) retain original or early nineteenth-century clapboards installed in a manner that is characteristic of the period. Made in 4’ lengths, these clapboards were skived by hand at each end to make a tapering lap joint with the adjacent clapboard. Clapboards were installed so that joints aligned vertically every second row, and, where possible, set to create a balanced pattern between window and door openings. Clapboards were face-nailed with rose-head nails set in vertical alignment with the studs, giving the exterior a neatly organized appearance.

Façade (east elevation) showing original window frames and clapboards, and the Greek Revival-style front doorway (ca. 1845)

View of clapboards set in four-foot lengths with skived joints vertically aligned every second course between windows at the second storey of the façade

The rear ell was covered with clapboards except for its rear (west) wall, which was constructed of brick and was exposed to the weather for a period of twenty to forty years. Like the majority of exterior brickwork of its period, this wall was coated either with white paint or white limewash that survives between floor joists that were set into it when it was enclosed in a new wing and its brickwork covered with plaster.

Roof

Original roofing materials do not remain, although it is probable that the roof was covered with wooden shingles during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Interior

As originally constructed, the house had a classic central-chimney floor plan with a staircase rising in three stages in front of the central chimney, two well-finished rooms (parlors) flanking the central chimney and a range of three rooms behind the chimney composed of a kitchen with cooking hearth (center) flanked by two service or storage rooms at the rear corners of the house. The second storey was composed of two chambers flanking the chimney and smaller chambers or storerooms beneath the slope of the lean-to roof. When the roof was raised to a full two-storey height (ca. 1790-1820) a range of full-height chambers was added to the west side of the second storey, and a plastered chamber was added to the south end of the main attic. This floor plan remains largely intact with the exception of the original kitchen which has been enlarged by joining it to the former southwest room and by the addition of a new staircase (ca.1880s) to the northwest corner of the house.

Interior finishes are ambitious for a rural house and retain an exceptional room of decorative painting.

Plaster: Most of the interior has been plastered with lime plaster set on exceptionally thick (⅜”-½”) accordion lath made of oak boards, which are fastened with hand-wrought nails in the locations where nailing is visible. Oak is a species of wood not frequently used for lath. In this installation, after being nailed at the top, boards were widely stretched providing broader and better spaces for plaster keys than is generally found in accordion lath.

View of back of the west wall of the northeast chamber showing accordion lath with heavily keyed plaster (ca. 1770)

Southeast chamber showing decorative wall painting with double row of rosettes over doorway (photo right) and eighteenth-century fireplace surround with crossettes

Decorative painting: The house’s southeast chamber bears decorative painting on all four of its walls. Unlike the stenciling found in the first half of the nineteenth century or the scenic painting of itinerant painters such as Rufus Porter, the walls are painted with a floral pattern that appears largely freehand, although the rough outlines may have been marked by a pounce or other method to provide lines to be followed by the painter. The wall surface may have been prepared with an overall ground of light gray on which the decorative patterns were painted with oil-based rather than distemper paints. Despite being covered with wallpaper for much of its history, the decorative painting has endured with strong colors. The removal of wallpaper may have taken some of the original paint, but sunlight seems to have been a more important factor in fading. Colors are most faded the room’s west wall where morning sunlight would have shone directly on the paint. Colors are strongest on the east wall where they would not have received direct light. The border with its brightly colored stylized flowers stands in aesthetically odd contrast to the more freehand floral pattern, but forms a continuous border around all panels in the room. Above the main door to the front stair hall, a double row of these stylized flowers indicates that the space was not planned with this decoration in mind, and that this double row was the painter’s method of filling up a space that was too wide to leave blank and too narrow to accommodate the floral pattern. The painted border has been cut back at the south window by the replacement of the original window’s splayed embrasure with perpendicular embrasures with a slightly wider casing. The border does not exist at the west door to the rear corridor, indicating that this doorway may have been added or significantly enlarged when the house was raised to two full storeys (ca. 1790-1820). This condition suggests that the decorative painting predates the house’s enlargement which would place it among the very early surviving examples of its type in New England. The bright yellow of the painted wainscot appears to be a modern addition painted over an earlier (if not original) base of gray/green.

Close-up view of the base of a decorative panel showing possibly original gray/green painted wainscot

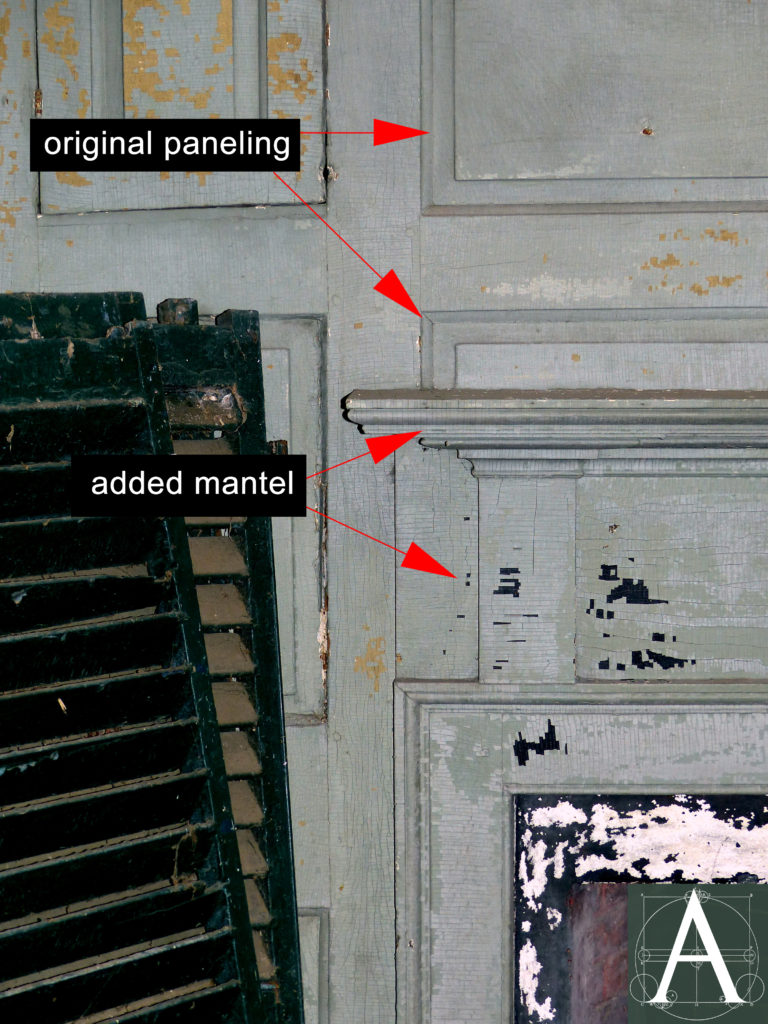

Woodwork: Both first-floor parlors retain paneled chimney walls on which firebox openings were trimmed originally with mouldings and no mantelpiece or mantel shelf – a common practice in the eighteenth century. The southeast parlor’s paneling has been adapted to the more widespread taste for mantelpieces in the early nineteenth century by the simple installation of a mantelpiece directly over paneling with no effort made to disguise that add-on. The northeast parlor retains a room end of paneling while all other walls are finished with high paneled wainscoting above which wall surfaces are plastered.

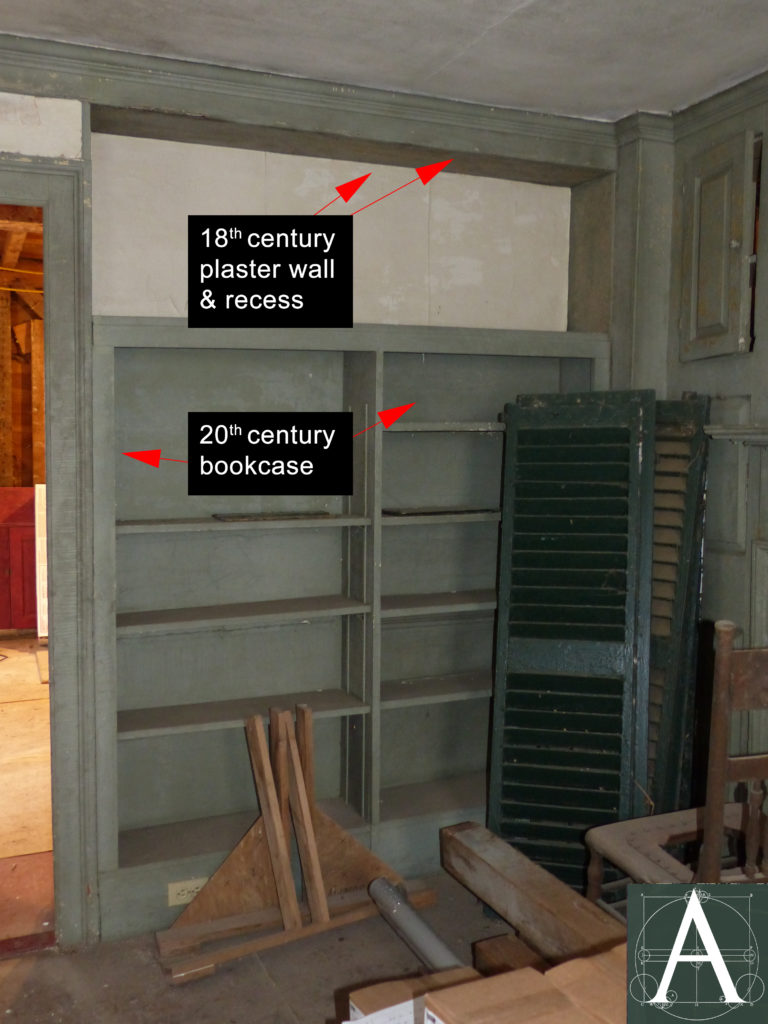

The southeast parlor contains an unusual detail in what appears to be an original plastered recess at the north end of its west wall, now partially filled with twentieth-century bookcases. Previously assumed to be a modern alteration for the purpose of creating a bookcase, the back of this bookcase has been exposed showing that its walls are made of lime plaster applied to oak accordion lath. The head of the recess is the boxed underside of a structural girt.

Pre-1820 recess with walls of lime plaster on oak accordion lath at the southeast parlor; original function unknown.

Locks: The Clayes House preserves a small number of locks that follow patterns seen in other buildings of the period. The house’s Greek Revival-style front door retains a keyed mortise lock (ca. 1840) with its original mounts and knobs. On the interior, the southeast chamber retains an iron stock lock (late 18th or early 19th century) set in a position that appears to be upside down. Such an arrangement was a common way to use locks that were made with a swing orientation that did not match the swing of the door for which they were needed. The other door to this chamber was secured only be a latch and eye hook. The only other lock in the main house dates from the late nineteenth century and is a Corbin rim lock mounted on a batten door for a linen/storage cupboard created beneath the attic stairs in the 1880s-1900.

Chimney: The central chimney retains much of its original shell (ca. 1770) but was altered in a highly unusual manner (ca. 1790-1820) to take advantage of advances in fireplace design that created more efficient fireplaces. The chimney rests on a base composed of fieldstone walls on three sides (east, south and west) and brick infill on the north wall. Within the base is a chamber formed by the side walls and large fieldstones laid across the wall heads to support the base of the chimney. These stones have not been quarried or tooled to fit more tightly, but have been used as found.

Interior of roughly formed stone vault at the base of the chimney, showing field stones that form the ceiling of the vault

Interior of original chimney showing back side of bake oven set on a base with clay mortar (ca. 1790-1820)

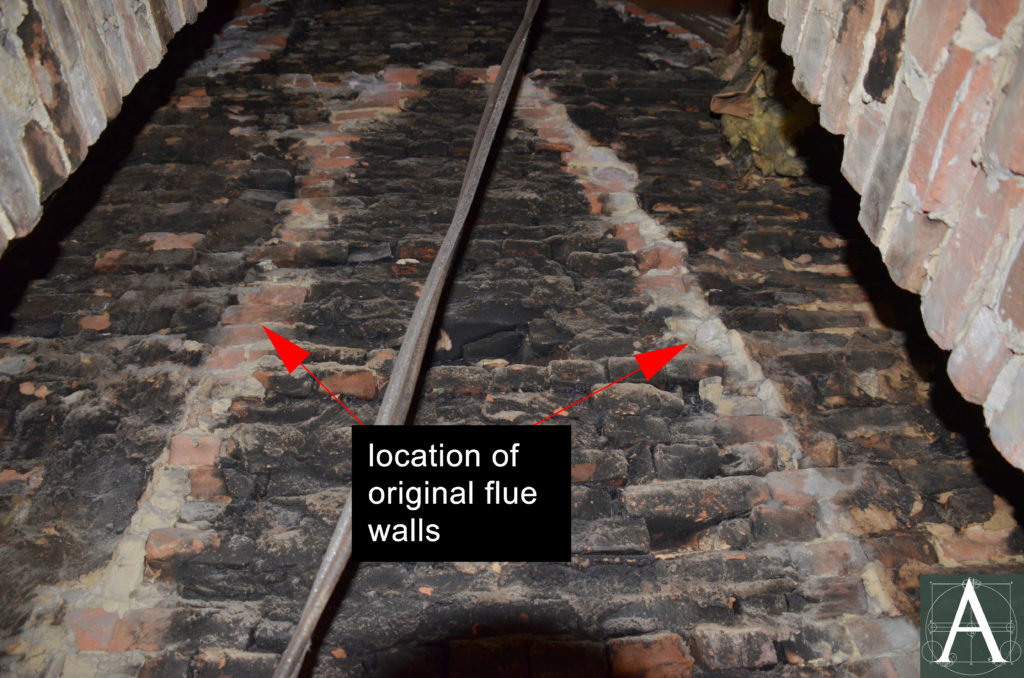

In the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, the chimney was disemboweled by the removal of the side and back walls of its fireboxes and its oven. A new set of fireboxes and bake oven were constructed using clay mortar for the base of the brick oven and lime mortar for other walls and new flues extending up through the original chimney. At the roof line, the chimney was cut back approximately one foot from its original face due to the smaller sizes of flues. Within the core of the chimney, this modification created a large, complexly shaped cavity. Lines of clean bricks in the soot on the east wall of this cavity show show the locations of the original flues for the northeast and southeast parlor fireplaces; however, the space between these flues is also darkened with soot as if an earlier cavity had been vented through a flue and used for burning.

Interior of the original chimney showing east wall laid in clay mortar; the lines of original flues appear as clean bricks in the soot

Interior of the original chimney showing original outer walls laid in clay mortar (ca. 1770) and new brick flues added within original chimney’s shell (ca. 1790-1820)

The chimney at the west wall of the rear ell appears to have been built to supplement the existing kitchen fireplace, perhaps by providing space for set kettles or other equipment. Although built at a time when quarried and hammered stone was becoming available, the base for this chimney is composed of two roughly built piers of fieldstone bridged by roughly split fieldstone, pieces of which have cracked, requiring supplemental supports. The hearth base extends between the two piers, above which is a large firebox; the stone that spans the south pier to the foundation wall may once have supported set kettles.

Interior of the rear ell’s chimney showing the south fieldstone pier (photo right) and the foundation (photo left) with hearthstones of roughly split field stone spanning the two.

Contributors

Historical background excerpted from “Historic Development Report: Sarah Clayes House.” William Finch & Carol Rose, 2014

Penelope Austin, Plasterer – on-site inspection, 2017

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian – on-site inspection, 2017

Sources

Historic Development Report: Sarah Clayes House. Finch & Rose 2014

Massachusetts Historical Commission, Inventory Form B: http://mhc-macris.net/Details.aspx?MhcId=FRM.512