Quarantine sign, ca. 1900 [from the The Quarantines of Epidemics Past (Stuhr Museum Grand Island, Nebraska)]

Writing in April 2020, when New England and most of the world are under some form of quarantine or lockdown order to slow the spread of the Covid-19 virus [officially named: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)], I am struck by the parallels between this pandemic and the outbreaks of smallpox that stalked New England throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Many of the debates of the period resemble those of today. How quickly does the virus spread? How can immunity for the community be achieved while avoiding large-scale loss of life from each individual becoming infected and either dying or recovering, sometimes with serious complications in the form of scarring, arthritis, malformation of bones in children, or blindness? How can effective treatments be found? How can the economic disruption of an epidemic be minimized? And, when is it safe to return to normal?

Although smallpox had no known cure and could also be transmitted before symptoms were evident, its final symptoms were unmistakable, unlike the Covid-19 virus, which can infect without symptoms or with variable symptoms. Smallpox was known to confer immunity on those who survived it, while this feature of Covid-19 is unconfirmed. Lacking a caregiver who was immune to smallpox, many who were sick with the disease suffered the symptoms, and sometimes died quarantined from their families and alone, much as now happens with Covid-19. Although we believe that medical science can find treatments and vaccines for the disease within a year or two, we now live in an unfamiliar state of uncertainty that seemed to have been banished in the past century.

Despite the old cliché that those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it, history is not a medicinal compound to be choked down for one’s own good. History stands at the core of culture, which is humanity’s greatest adaptive tool, cumulatively building upon the knowledge and experience of past generations, even though we often forget old truths learned by previous generations. Hearing from the past in its own words can offer different ways of seeing our own lives, and comfort that people have endured and overcome challenges more frightening than those of the present.

Smallpox treatment and Pest houses before 1716:

Some writers observe that New England was founded upon smallpox. As early as 1619, when Thomas Dermer sailed from Monhegan southward along the New England coast looking at potential sites for English settlement, he found in the vicinity of Plymouth, Massachusetts, “…some ancient Plantations, not long since populous, now utterly void.” Through the enslaved Native American who translated for him, Dermer learned from survivors of an illness that decimated their tribes. While measles and other European diseases killed Native Americans, smallpox seems to have been the most persistently virulent, having been brought here by fishermen and traders, perhaps as early as the late sixteenth century.

As early as 1633, merely three years after the English settlement of Massachusetts Bay, smallpox spread through the Native American population, killing “almost every native as far north as the Piscataqua and destroyed some 300 Narragansetts to the south.” Subsequent outbreaks in 1636 and 1659 caused the General Court to meet outside Boston to avoid the contagion. In 1647, the spectre of smallpox appeared in reports from the West Indies that a “greivos [in]fectious disease, hath lately exceedgly raged…to ye great depopulatn of those [places].” The Governor and Company gave orders in March 1647 that all vessels from the West Indies were to anchor at “ye Castle” in Boston Harbor and no person in a vessel from the West Indies should come ashore or come within four rods (66 feet) of any other person not part of the vessel’s company. Each offense was to be subject to a fine of 100 Pounds. Before passengers, crew, or cargo could be landed, the approval of the General Court or three of its members was required. This order was sent to all towns and instructions given to designate “some convenient place, upon some of ye ilands or othr fit places, where such psons & goods shalbe sheltered for a time, & to do any thing of like nature yt shall be necessary for their preservation, & welfare of ye country.” [Shurtleff, ed., v.2, 237-238]

Although medical knowledge of the period was overwhelmingly empirical and untested by the rigors of the scientific method, physicians understood that smallpox was primarily transmitted through close contact with droplets expelled by the coughing and sneezing of infected people, and that inhalation was one of the primary points of entry for the virus, much as Covid-19. They also understood that separating the infected from the uninfected was the only effective method of stopping the disease’s spread. From the earliest appearance of smallpox in the New England colonies, towns sought to quarantine those infected with the disease in distant locations, preferably islands or the outer edges of settled communities for periods of fourteen to twenty days. Waves of smallpox outbreaks occurred; in Boston, there were eleven in the seventeenth century and a similar number in the eighteenth. Outbreaks could be as small as that of 1666 when only 40 people died; however, those of 1677-1678 and 1697 were calamitous. In the latter, there were 1,000 deaths out of an estimated population of 7,000-8,000. [Woodward, 1182.]

In the face of a rapidly growing smallpox epidemic in 1701, the Province of Massachusetts Bay passed “An Act Providing in Case of Sickness” empowering the selectmen of towns to quarantine people coming from other places where contagion was known recently to have existed or those who had symptoms in a “separate house or houses” and to provide them with nurses and “necessaries for them at the charge of the partys themselves, their parents or masters (if able), otherwise at the charge of the town or place whereto they belong.” [A&RMB, v. 1, 469-470.] This act appears to authorize the creation or designation of quarantine houses, known more commonly during the period “Pest-houses,” a name dates from the early seventeenth century. Spelled variously in an era of non-uniform spelling, the name was derived from the old word for plague, “pest” or “peste.” Documentation of such buildings before 1714-1716 is lacking [Information Needed].

1716-1721 – Changes in Smallpox Treatment and Quarantine:

By 1716, the Province of Massachusetts Bay began to use Spectacle Island in Boston Harbor for quarantine. On June 16th of that year, Samuel Bill, owner of the island, presented a bill of 20 Pounds for “the Damage he has sustained by Infectious Persons being put ashoar by Authority several times, upon his Island called Spectacle-Island.” By October, 1717 a hospital building was under construction on the island at an initial cost of 173 Pounds. On November 1, 1718, William Payne and Samuel Thaxter were paid 20 Pounds, 7 pence for “finishing the Publick Hospital, and a Fence there.” Despite these payments, it is unlikely that the building had been fully completed. On November 17, 1719, Samuel Bill again petitioned for damages:

A petition of Samuel Bill of Boston, owner of Spectacle-Island, on which the Province-Hospital is built, was presented to the House & Read, praying, That he may be paid for the Damage that was done upon said Island by Seventy Passengers Landed there, who cut down several valuable Trees there, and spoiled the Grass, being done while the Hospital was building.” [JHR, v.2, 201.]

That the people quarantined cut trees suggests they were cut to provide firewood. The destruction of grass may indicate grazing land trampled by the number of people crowded onto the island. Subsequently, on November 10, 1720, the General Court issued an order:

…that the Select-men of the Town of Boston be desired to take care for the finishing of the Publick Hospital on Spectacle-Island, so as to make it warm and comfortable, for the Entertainment of the Sick; and that they supply Necessaries to such as are there, and not able to Provide for themselves.” [JHR, v.2, 280.]

After a gap of nineteen years during which Boston had no major outbreaks, perhaps due to the careful enforcement of quarantine on Spectacle Island, a generation grew up without exposure and without immunity to smallpox. When the disease reappeared in 1721 with the arrival in April of the British warship Seahorse, the community became alarmed. Despite having two sick men on board, the ship by-passed the quarantine station and landed directly at Long Wharf on April 22nd. By May 8th, word circulated through the town that one infected seaman had come ashore and a case of the disease had appeared. On May 18th, the selectmen ordered the ship to the quarantine station on Spectacle Island, but it was too late.

As the epidemic advanced, Cotton Mather (1663-1728), a member of the third generation of prominent Puritan ministers, stepped forward to become a major force in introducing smallpox inoculation. A polymath with interests as diverse as astronomy, medicine, and the hybridization of plants, Mather initially learned of the practice of variolation (inoculation) from his enslaved servant, Onesimus, who described the practice in his home country, perhaps Ghana. By 1716, he had read an account of a practice that was common in Asia and the Levant, written by Dr Emanuel Timonius of Constantinople and published in The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, an organization known more commonly as the Royal Society, into which Mather had been elected a Fellow in 1713 for his own scientific contributions to the organization. The method of inoculation required taking infected material from smallpox sores and introducing it into the body of a healthy person through a cut in the skin that was then sealed over. Inoculation induced a weaker form of smallpox than that acquired by the virus’s “natural” method of entry through the respiratory system. In a letter to the physicians of Boston on June 6, 1721, Mather cited Timonius and other sources while exhorting the physicians to come together to discuss and attempt the practice to slow the epidemic. None replied.

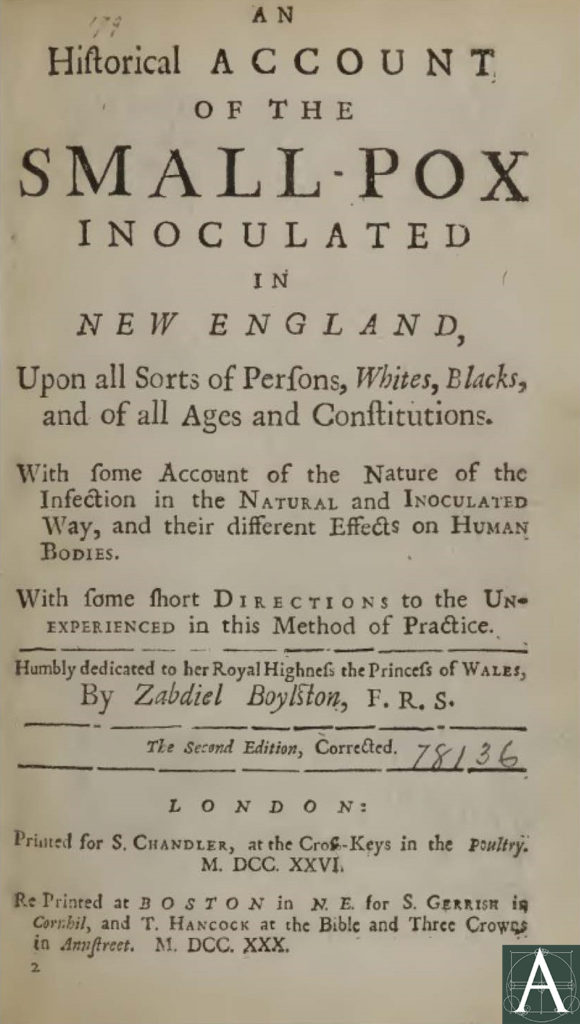

Mather then approached Zabdiel Boylston, who “had a reputation as a successful surgeon who was also willing to undertake risky procedures…[including] a total mastectomy (without anesthesia)” from which the patient survived. In June 1721, Boylston inoculated his son, his enslaved servant, Jack, and Jack’s son, Jackie, all of whom experienced milder infections of smallpox and emerged immune. Boylston kept systematic records of each of the 253 people whom he inoculated in 1721-22 of whom only 6 died. After the epidemic passed, Boylston was invited by the Royal Society to visit London and present his findings. With an introductory note of apology to patients whose names and conditions he revealed for the benefit of medical knowledge and mankind without having had time to seek their approval, Boylston published while in London the name of each patient, the patient’s condition before inoculation, the date of inoculation, the course of the patient’s smallpox reaction, and the outcome.

Title page from Zabdiel Boylston’s An Historical Account of the Small-Pox Inoculated in New England. (1726)

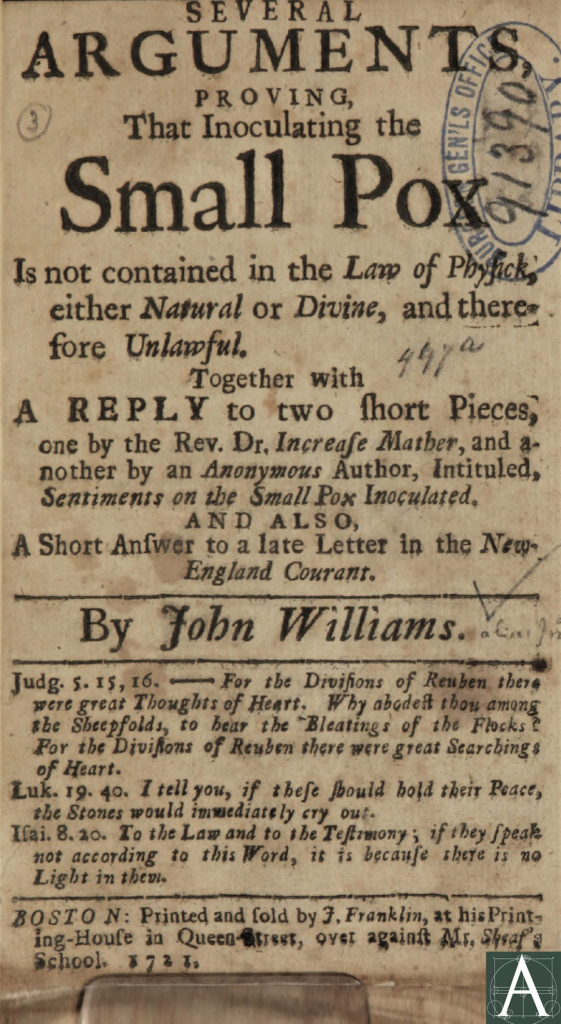

Inoculation stirred long-lasting and bitter controversy. Many Puritan ministers regarded it as a violation of God’s order, while physicians regarded it as dangerous to infect intentionally, and the public feared greater contagion. The controversy continued for over fifty years with towns periodically outlawing the practice before finally accepting its efficacy. It led to a gradual distinction between pest houses where the sick were tended while waiting for nature to take its course, and inoculation hospitals where healthy people received inoculation and stayed under the care and observation of a doctor and nurses until their infection ended.

Title page of “Several Arguments Proving that Inoculating the Small Pox Is not contained in the Law of Physick, Either Natural or Divine, and therefore Unlawful.” by John Williams (1721) – one several writers who fueled the bitter controversy around smallpox inoculation. [Image from the National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine.]

In the absence of surviving structures and objects, governmental records, similar objects found elsewhere, and diaries provide the best clues as to how New Englanders experienced these periods of contagion and quarantine.

Housing the Sick: Pest Houses

Too few descriptions of purpose-built pest houses survive to determine if they formed a distinct building type. More likely, they were domestic in scale and resembled houses of the period but with simple finishes. Occasionally, private homes outside the town centers were requisitioned as pest houses, such as “now taken up for an Hospital at the Westerly part of the Town – According to Law” by the Town of Boston on November 25, 1738. The selectmen ordered “mr. Savel be directed to hang a red flag” from the house and to send a half cord of wood, presumably for heating. “Nurse Maccoy was sent to the said Hospital on Monday the 27th Current and a Girl sent to Assist mrs. Foster in nursing at her House, the same Day. And —- a Jersey man was appointed as a Watchman at the Hospital on the Lords Day, Nov. 26th.” Similar action was taken by the Town of Providence, Rhode Island during the outbreak of 1751, when the house of Thomas Kinnicut was taken over at the order of the General Assembly for use as a smallpox hospital. When the outbreak had passed, Kinnicut presented a bill “for damage to his house through its use for a pest house.” A small amount of documentation exists for the following pest houses:

1737-1738 – Boston – Rainsford Island Pest house:

In 1736, the Province allocated 570 Pounds to be used by the Selectmen of Boston to acquire a new site for a “Hospital for the Province,” of which 130 Pounds were to come from the sale of the existing pest house on Spectacle Island, where the presence of abutting property owners may have made quarantine more difficult. Rainsford Island was purchased in its entirety and by October 13, 1737, the committee appointed to this task reported the construction of a building:

…shewing they have built an House there of four Rooms on a Floor, four upright Chambers, and convenient Garrets, and Cellars, well finished, and a Well, and suitable Conveniencies for the Reception of the Sick, as the Occasion may be. [JHR, v.15, 162-163.]

The description appears to be that of a typical New England, timber-frame house with four rooms on the first storey, four rooms of full height (“upright chambers”) on the second storey, and additional chambers or usable space in the attic (“Garrets”). By January 1744, it had become apparent that confining infected and uninfected people in the same building created needless extra disease and expense. The Town of Boston proposed to construct an additional house on the island, arguing:

That there being but One House on Rainsfords Island…Occasions many Inconveniences as well as Expense to the Province by reason that every One both Sick & well Persons are Obliged to remain in the same House, whereas if a Separate One was Built tho’ of but One Room & a Chamber not only those Persons who have formerly had the Distemper might be much sooner Released from the Island than they possible can now…” [BSM, v.17, 93.]

In 1777, this structure was called the “Well House.” In 1782 a new hospital building was constructed and it was noted that “Mr. Payne is also to make twenty new Cribs for the use of the Hospital.” It is not clear what is meant by cribs in this context but the quantity of the order suggests they may have been some sort of bunk bed or other partially enclosed bed, perhaps resembling beds in the roughly contemporaneous Nantucket Gaol (pre-1805). In 1789, the new hospital became an inoculation hospital. In 1803, reflecting the widespread acceptance of inoculation, Rainsford Island was divided into three zones. The eastern side was marked with flags – presumably the red flags used to mark private houses where infection existed – where the quarantine hospital existed, a separate zone for the Convalescent and Well, and another zone containing the Spears House where “Gentlemen with their Wives, children: The visiting physician may permit persons of this description and such whose peculiar valuation requires it to take lodgings at Spears House [home of the Island Keeper].”

Nantucket Gaol (c. 1805) two of four bunk beds built in a shared room with fireplace that may resemble the “cribs” built for the Province Hospital and Rainford Island in 1782

1752 – Newbury, Massachusetts – pest house on Plum Island:

In March 1752, the Newbury selectmen established a committee to inspect ships that came into the Merrimack and Parker Rivers for passengers or crew that were sick with smallpox. The committee was also authorized to build “a dwelling-house on Plum island, ‘near the upper end of said island,’ for the town’s use” in quarantining potentially infected passengers or crew.

1760 – Durham, Connecticut – pest house near Pisgah Mountain:

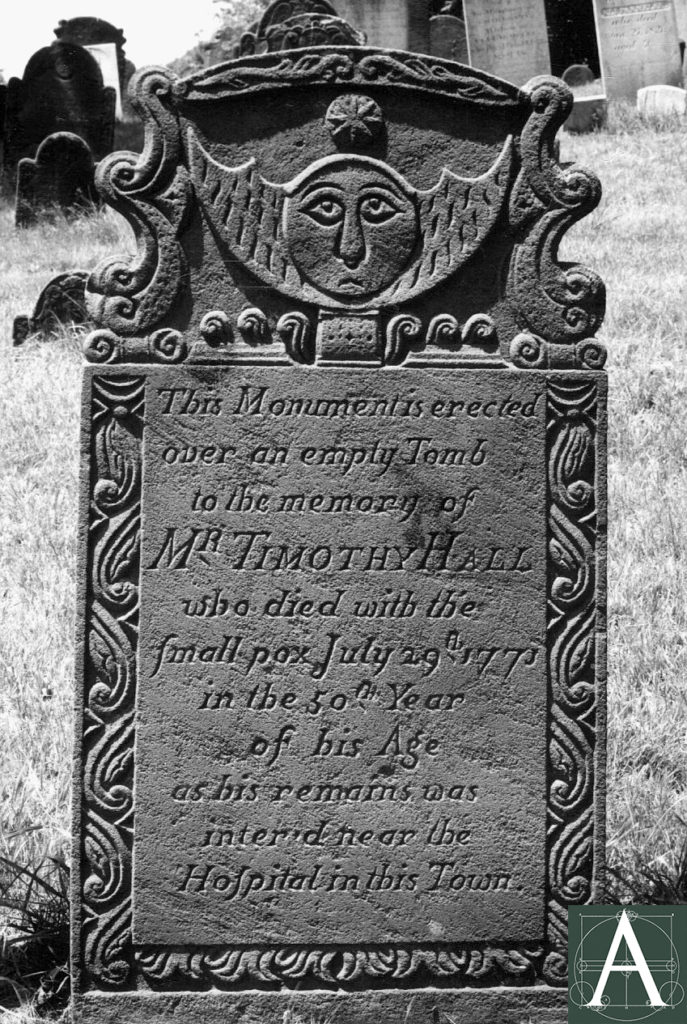

In November 1759, John Jones of Durham, his wife, and daughter all contracted smallpox and died from it within a month, presumably in their own house as the town did not have a pest house or “hospital” in which to isolate patients with communicable diseases. The following spring, the Town voted to build a quarantine hospital in a location distant from the town center, northwest of Pisgah Mountain near Cream Pot Road. The building was 30 feet long and 20 feet wide of wood-frame construction covered with clapboards. It was equipped with a chimney and a well. This pest house remained in operation from 1760 into the 1790s during which time 31 patients died and were buried near the hospital rather than in the town’s cemeteries. It is possible that one of these patients was Timothy Hall, whose gravestone in the local cemetery notes that his body was buried elsewhere.

1763 – Newbury, Massachusetts – pest house at the great pasture:

Shortly before the Town of Newburyport separated from the Town of Newbury, the selectmen voted “to build the Pest House in the great pasture, to be 38 feet long, 28 feet wide and one story high.” From early in its history, this pest house was used variously for inoculation and quarantine of smallpox patients.

1769 – Newburyport, Massachusetts – hospital/pest house on Plum Island:

In 1769, the Towns of Newburyport and Newbury shared the cost of building another quarantine building on Plum Island. Ships arriving in the harbor of the Merrimack River were required to wait for inspection at a point below the “half tide rocks.” Use of the building was sufficiently erratic that when faced with the arrival of infected travelers due to an outbreak in Boston in 1776, the selectmen ordered the town constables to go to Plum Island “where Joseph Bootman and others dwell, you are directed to give said Bootman & whoever else you may find there, notice immediately to leave the said House and in case they refuse to do you are forthwith to remove them therefrom.” The next day, the selectmen ordered James Kettell, constable, to conduct an infected sailor from the Schooner Polly and place him “in [the] charge of a competent nurse in the house on Plum Island.” By September 1780, this building was no longer needed and was “bro’t up from Plum Island to ascertain the cost of repairing it.” By the following March the Overseers of the Poor, who had considered its use as a poor house, and the selectmen decided not to repair the structure. It was disassembled, and the materials were sold.

1781 – Portland, Connecticut – pest house:

Only fragmentary information on this house is available based upon the diary of William Syckman. On February 12, 1781, Syckman wrote of having difficulty sleeping due to sweating and nightmares as well as the recollection of being taken from his home, presumably against his wishes by local authorities, to be quarantined in a pest house in the woods. Syckman’s additional diary entries refer to hallucinatory figures moving about the room, watching a rat feed on his lunch as well worrying about what will happen when his food runs out. Interesting as the diary entries are, they were published in modern English lacking the syntax of the eighteenth century, and they were quoted without identification of the location of the repository in which the diary survives. The name “Syckman” seems possibly a spoof. If the original diary can be located, it would provide an interesting firsthand view of one person’s experience of solitary isolation for smallpox in the late eighteenth century; until such time, the diary should be regarded with some skepticism. [Information Needed]

1824 – Portland, Maine hospital/pest house:

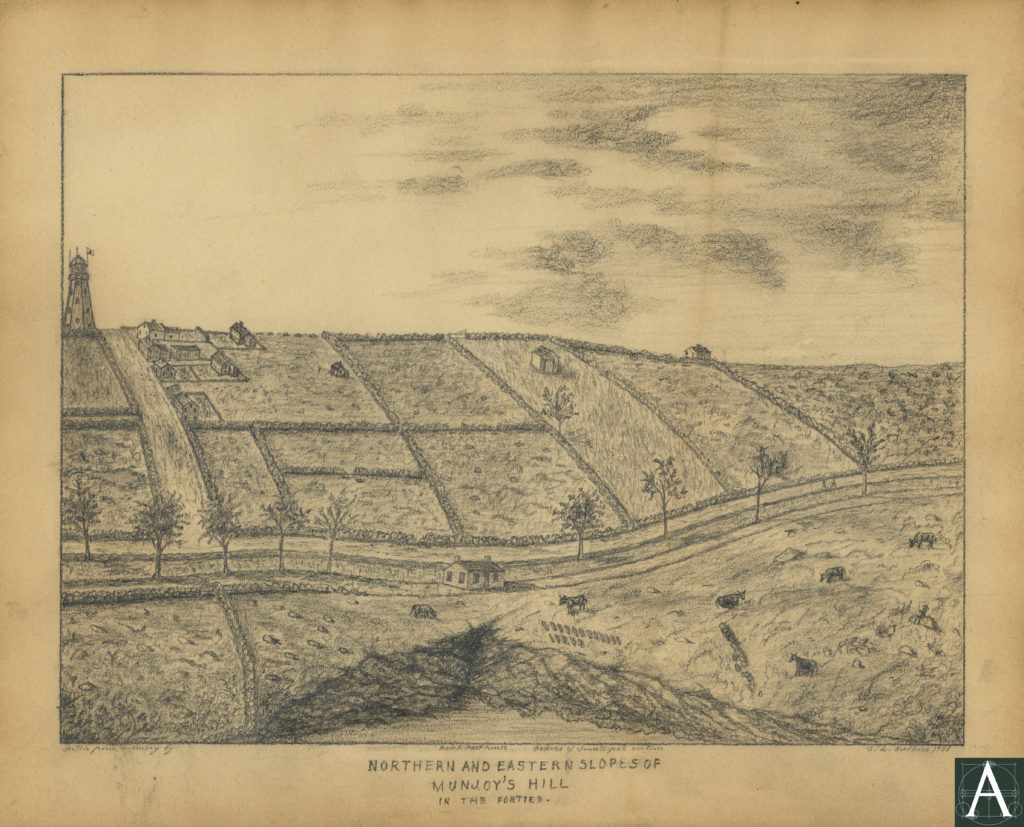

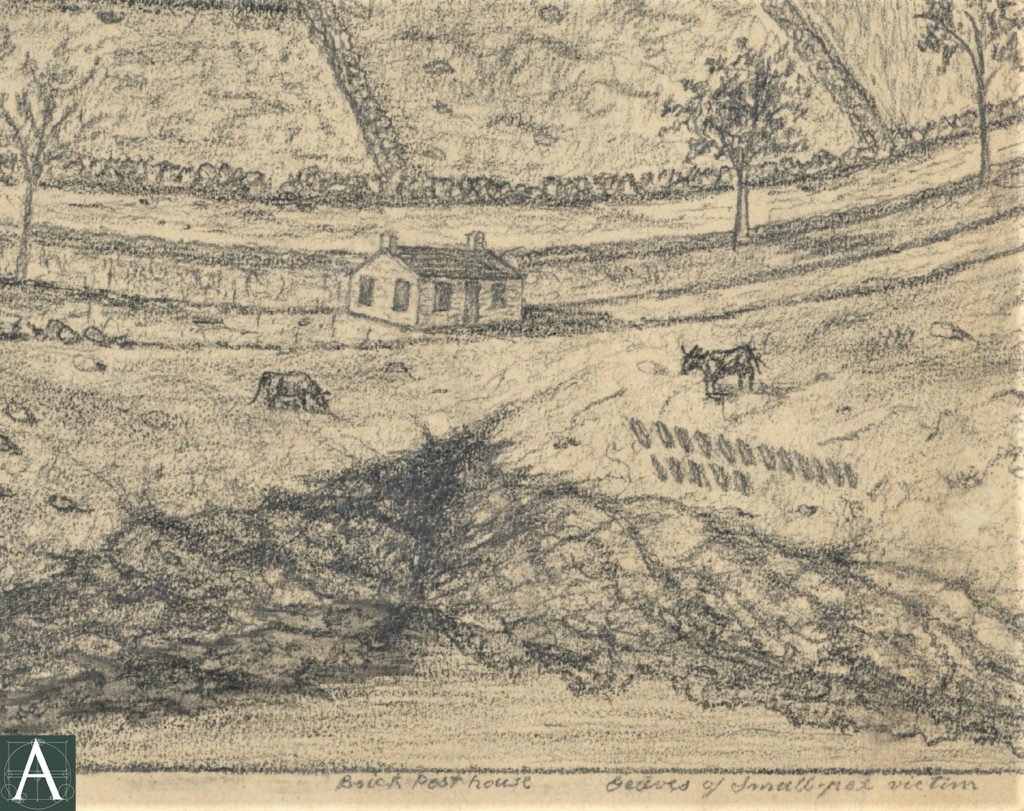

Northern and Eastern Slopes of Munjoy’s Hill in the Forties, drawn from memory by Charles Goodhue (1901), showing the Portland Pest House in the center foreground as remembered in the 1840s. [Courtesy of the Maine Historical Society]

Detail of Northern and Eastern Slopes of Munjoy’s Hill in the Forties, drawn from memory by Charles Goodhue (1901), showing the “Brick Pest House” and “Graves of Small-pox Victims” as remembered from the 1840s. [Courtesy of the Maine Historical Society]

Inoculation Houses:

Inoculation houses tended to be privately owned, perhaps purpose-built, by physicians who administered the inoculations and tended the patients whose symptoms were much milder than smallpox acquired “the natural way” through inhaled virus from exposure to infected people. The practice remained controversial through most of the eighteenth century as townspeople and physicians feared that inoculation with live smallpox virus would spread the virus and cause more epidemics. For this reason, these buildings tended to be at the periphery of communities, sometimes using unoccupied pest houses.

Typical of the ambivalent relationship many communities had to inoculation houses, the Town of Nantucket encouraged Dr. Samuel Gelston to operate one on the island. In 1771, Gelston selected a site on Gravelly Island near Madaket at the southwest corner of Nantucket. Inoculations began to be administered until islanders complained that some of the patients had been so careless as to endanger the health of townspeople, perhaps by wandering close to settled portions of the town. Inoculations were suspended for a period but resumed in 1778. Again, islanders worried that their health was being endangered. The controversy was settled by the Town’s purchase and closure of Dr. Gelston’s “buildings at cost…viz: ₤1,072 17s. 6d. old tenor.”

Later in the eighteenth century as the efficacy of inoculation became more widely accepted, some inoculation hospitals offered amenities to create more of a resort. Patients whose symptoms were mild quickly grew frustrated at the confinement of quarantine for the full period of two or three weeks until they could be certified as infection free. In 1792, a private hospital on Ram Island near New London, Connecticut, opened to patients of both sexes and offered a number of luxuries and opportunities to socialize “including a darky fiddler, for dancing.”

Private Houses:

Many who became ill with smallpox preferred to remain at home for care, presumably by relatives or servants who had acquired immunity through infection and recovery from the disease, although local selectmen and town councils preferred to remove the infected away from centers of population.

In Providence, Rhode Island, the Town Council book records in 1760 that “Sarah Brown is now Ill with the Small Pox at the House of Isaiah Hawkins.” The Council summoned four men, perhaps constables, “to Remove the said Sarah Brown to the Pest House – the Clerk of the Council is hereby directed to provide a Box [presumably a closed sedan chair] for to remove the said Sarah in.” The next day three of the men returned to the Council with a certificate from Dr. Henry Stirling to protest the removal. Either the patient was too sick or too infectious to be moved. Consequently the Council voted: “Resolved that the said Sarah not be Removed, and that the Clerk of the Council Grant forth a Warrant to order Isaiah Hawkins and family to Remove and to fence up the Highway in Two places, Grant a Summons Requiring Richard Young to Goe forthwith and nurse the said Sarah Brown.”

In a similar incident in Boston at a Selectmen’s meeting in August 18, 1777:

Information being given that the Wife of Mr. Poor the Blacksmith at a House in Wings Lane, is taken with the Small Pox – whereupon Mr. Poor was sent for – and informed that his Wife must be removed to the Hospital at New Boston & he was desired to reconcile her to such a measure. [BSM, August 18, 1777, 46.]

The necessity of reconciling Mrs. Poor to a stay at the Hospital/Pest house would suggest that some, or perhaps most, patients dreaded or opposed such a move that took them from their families to an unknown place that was perhaps overcrowded with other smallpox patients and care of uncertain quality. The next day, the Selectmen reconsidered the situation:

The Selectmen having been opposed in their attempt to remove Mrs. Poor with the Small Pox to the Hospital & the situation of the Woman being such as would make force dangerous – It was Voted, that the House would be shut up, a Red Flag hung out, a Guard placed, and Fences Erected to prevent a communication of the Infection & Capt. Preston desired to see the same executed. [BSM, August 19, 1777, 47.]

For those who remained in a private house, quarantine with a guard was common practice, as was the hanging of red flags bearing the words “God have mercy on this house.” Temporary fences were routinely constructed to encourage all passersby to keep their distance. In the midst of the outbreak of 1752, the Boston Selectmen “according to Law directed the red flaggs to be hung out at all such places where it [smallpox] is, and such of the Inhabitants in whose houses the Small Pox may here after break out to give them immediate notice thereof. And the Select men direct that no person after this Day come into Town to be inoculated, for if they shou’d such will not be permitted to tarry here & have it but be sent back to the place they came from, or to the Province Hospital on Rainsford Island at their own expence.”

One other reason for citizens to avoid the pest house was cost. Various statutes throughout New England called for the community to be reimbursed for the costs of nursing care during illness. Statutes as early as 1701 provided for repayment of the costs of lodging and nursing care “at the charge of the partys themselves, their parents or masters (if able), or otherwise at the charge of the town or place whereto they belong.” In the case of Benjamin Sprague of Malden who had been quarantined at the pest house on Rainsford Island, the 10 Pound charge for his care in 1777 remained unpaid in 1778. On March 25th, the Boston Selectmen wrote to the Selectmen of Malden:

Gentlemen –

We informed you sometime past that your Town was indebted for the support of Mr. Benjamin Sprague one of its Inhabitants, at the Hospital at Rainsfords Island when under the Small Pox, Ten Pounds on account of particulars has been also sent, but we have not as yet received payment or so much as a Line from you. We are loath to commence a Suit & would therefore once more pray you to discharge the sd. Accot. or that you will be pleased to give us the reasons that prevent you –

By Order of the Selectmen

William Cooper Town Clerk.

[BSM, March 25, 1778, 62.]

A more complicated and expensive case of mandatory quarantine occurred in 1744 when the Billander, Young Eagle, a Privateer sailed by Captain John Rouse arrived at Boston on April 2nd. Rouse reported to the Selectmen through “Mr. David Brooks from Connecticut,” whom he met at the lighthouse, that several of his crewmen were sick with smallpox. The last English port the ship had visited was in Jamaica, four months earlier, after which the last land seen from the ship was the Bahama Islands, eight weeks earlier. Rouse speculated that the disease was Communicated to them by a Jamaica Privateer what was in Company with them [at] Morherc Key” eight weeks prior to his arrival in Boston. Of the eighty crew members, nine had been infected with smallpox of whom one had died and six were recovering; the fate of the remaining two was not mentioned. All but twelve of the remaining crew had previously had smallpox, rendering them immune to the infection. When Rouse made his first report, the ship was down to less than a week’s worth of provisions. The Selectmen immediately ordered the ship to Rainsford Island where provisions were sent, and the sick men were ordered to stay on the ship, while the healthy and recovered men were sent ashore to the island. Rouse’s wife petitioned the Selectmen to join her husband and was sent to the island to stay until her husband should be released from quarantine. Captain William Phillips was appointed a guard to assure that the infected crewmen were kept separate from those who were well.

Anticipating a high cost for the quarantine, the Boston Selectmen immediately petitioned the Great & General Court to “take into Consideration & direct how the Charge shall be Born in Supporting the Well Persons who are Confined with those Sick of the Small Pox at the Hospital on Rainsfords Island.” Slightly more than two weeks later on April 19th, “the Select men went down to the Hospital at Rainsfords & (after Washing, Cleansing & Shaving) Dismissed nine of the Sailors…& Supplied them with Fresh Cloaths at the Province Charge.” After all men and the ship had been released, the Selectmen petitioned the Great & General Court to pay the high cost incurred in their care – 953 Pounds, 10 shillings, and seven pence, Old Tenor. For reasons not mentioned in the Selectmen’s minutes, no apparent effort was made to assess the costs on the owners of the Young Eagle or individually on the crew and Captain Rouse.

Gates & Guards at Bridges:

In addition to mercantile ships as a possible source of infection, travelers by land were a source of concern during outbreaks. Wherever communities had bridges or ferries that could be used to control the entry of infected travelers, they moved quickly to establish gates and guards. In 1752, at the outset of a major outbreak, the Rhode Island Assembly established eight bridges and ferries to which it assigned guards to stop and question all travelers seeking to enter the colony. The guards were selected from people who had had smallpox and were immune to further infection. Guards questioned travelers if they were traveling from a place with infection and if they had immunity from having had and recovered from small pox. Those who were immune or could satisfy the local authorities that they had no exposure were issued a certificate of compliance with “The Act to Prevent the Small-Pox being brought into the Colony by Strangers and Travellers coming from infected places” after being “thoroughly cleansed , and shifted with fresh Cloathing” (see Disinfection below). Those who could not demonstrate immunity were required to “tarry” outside the colony for twenty days’ observation. If symptom-free after twenty days, travelers were given a certificate of compliance and allowed to enter, after the usual “cleansing” and fumigation.

The Town of Boston set up a similar set of gates at the Roxbury Neck, which was the only land access to the town. The towns of Newbury and Newburyport shared the costs of setting up and guarding bridges over the Parker River in 1764 and 1776.

Transporting the Ill:

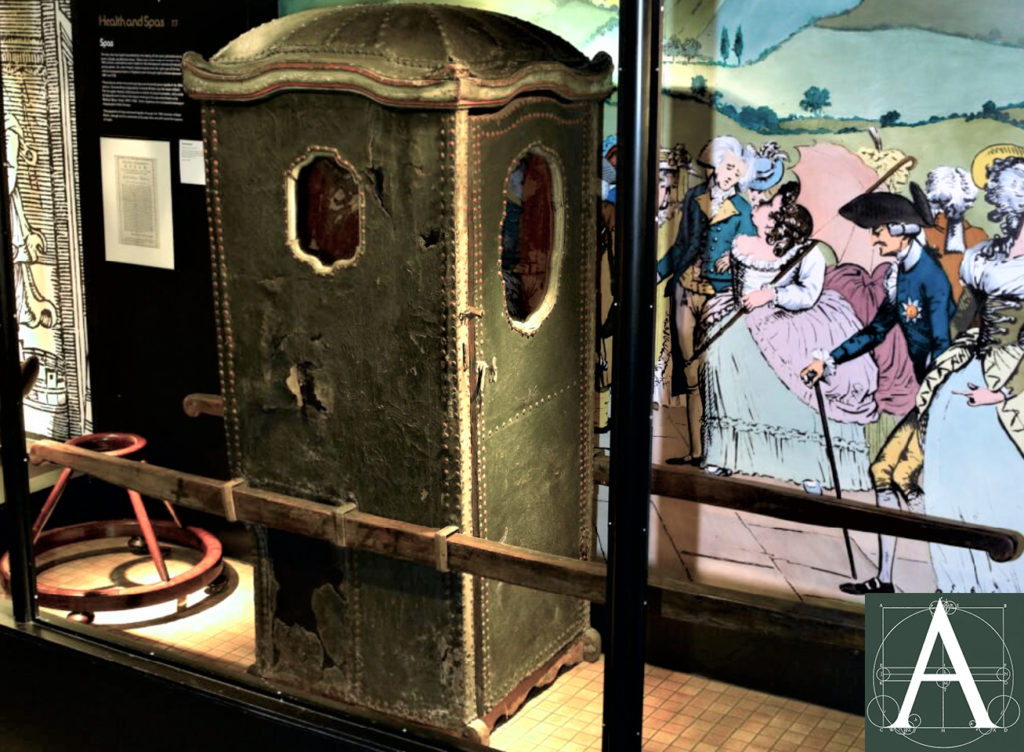

Moving ill and contagious people through densely built town centers to a pest house was a subject of concern to every community, especially if the patient was opposed to being moved, as Mrs. Poor evidently was in Boston in 1777 (see Private Houses above). Two references suggest that closed sedan chairs were one of the methods of moving contagious patients through a town. The “Box” that the Clerk of the Providence Town Council was directed to provide for the removal of Sarah Brown to the Pest House in 1760 was nearly certainly a closed sedan chair, in overall form probably like, but less elaborate than one from South America contained in the collection of the Science Museum Group (see illustration). Boston’s Selectmen’s records are more explicit about the use of sedan chairs. At the beginning of 1757, the Selectmen inspected the pest house and ordered “Beds & Cribbs for the Sick at Ransfords Island” in addition to ordering “that the Sedan for Removing the Sick be broke to Pieces. Voted that Mr. Cazneau make a good Serviceable Sedan at the Charge of the Town.”

A Sedan Chair (18th century) used in La Paz, Bolivia to carry patients to hospital – may resemble sedan chairs used in Boston to move patients to quarantine [Object #A634685 from the Collection of the Science Museum Group.]

Disinfection:

Several methods of disinfection were routinely practiced throughout New England. Among the most commonly mentioned methods in historical records are:

- Brimstone (sulfur) was burned to produce smoke containing sulfur dioxide (SO₂) which has anti-microbial properties known since classical antiquity when Odysseus upon returning to his house and slaying the would-be suitors of his wife, demanded of an old loyal servant: “Bring me brimstone, old dame, the cure of evils, and bring me fire, so I can sulphur the hall.”

- Vinegar was routinely used to wash down surfaces after ships and their cargos had been “smoked” with brimstone. Its acidic chemistry was also a disinfectant known since classical antiquity, and earlier.

- Lime [calcium hydroxide – Ca(OH)2] was occasionally used to disinfect surfaces. An essential component of mortars and plasters of the period, this material served into the twentieth century as a disinfectant wall coating in milk rooms, cellars, and attics. Thinned with water and applied as a limewash or whitewash, lime’s base pH is anti-microbial upon application but cures by the absorption of carbon dioxide to form a coating of calcium carbonate, which is a more moderate base. Applied in this manner, lime cures to an opaque white surface suitable for architectural application but damaging to other materials.

- Light and air – leaving objects and cargoes in the open air and sun for a period of time was also practiced to disinfect objects that could not easily be treated by other methods.

References abound for “smoak houses” near quarantine hospitals in ports and at bridges where gates could be placed to control the arrival of outsiders during outbreaks. The scale and design of these structures is undocumented by contracts, descriptions, or images. They appear only as passing references during epidemics. In Rhode Island, the Assembly voted to pay 15 Pounds to Benjamin Tallman “for Pine Boards by him provided for the Smoak-House at Bristol Ferry.” Elsewhere, Boston maintained a smoke house on the Roxbury Neck, a narrow strip of dry land that provided the only over-land access to the town during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By 1740, another smoke house stood near the “Hospital at the Westerly part of the Town” to which the Boston Selectmen sent two bags of letters that had arrived on a ship from London on which three crew members had been infected with smallpox. The Selectmen ordered that the letters be “thoroughly Smoak’d & air’d” before being returned for distribution.

Typical of the methods of quarantine and cleansing of ships was those carried out on the Joseph following its arrival in Boston Harbor on July 29, 1736 after an eight-week voyage from New Castle, England. The ship’s captain, Joseph Riddle, reported that some of his crew had suffered smallpox during the voyage. Acting on this information, “The Select Men together with Mr. Justice Sewall, and Doctor Davis went on board said Ship, in order to Examine into that affair.” The group determined that three members of the crew were then ill, and that “they had not yet thrown over the Bedding and Cloathes of those that had been Sick, which as now Ordered to be done, and was immediately Executed in our Presence,” the Selectmen ordered:

That the said master be, and hereby is Directed to move his said Ship near to the Pest House, on Spectacle Island, and there to put on Shoar, his Glass, and to burn the loose Straw Covering the same, and to keep the Glass out of Doors; To put the Persons that have been Sick on Shoar there also, Who are to remain there for the present, as also his Whole Company are ordered to air themselves and their Cloathing, and to Cleanse, Scour and air the said Ship by Burning Brimstone and Washing between Decks with Vinegar; to run out his Cables to Wash them in the Water, and when taken on board again, to Quoil them on the Deck, And Further, to Suffer no Body to come on board without Leave of the Select men; And thus to Remain, until further order. [BSM, v.13, 308.]

On August 4th, the Selectmen concurred that Captain Riddall had carried out their previous order. Consequently, the board voted:

These may Certify, that We apprehend no Danger of Infection from the said Vessell, But are of opinion She may come into this Harbour with Safety to the Inhabitants, While the Three Persons aforesaid, and the Glass be continued at said Island until further order. [BSM, v.13, 308.]

Burying the Dead:

Memorial gravestone of Timothy Hall was placed in the town burial ground, although his body was buried at the smallpox hospital/pest house due to concerns about contagion in 1771 [image from the Farber Gravestone Collection of the American Antiquarian Society]

Where burial took place near settled portions of a town, some communities set strict rules on the preparation of the coffin, the route by which the body could be carried through the town, and the limited number of people who could be present at the burial. On September 17th, 1759, the Providence Town Council granted permission to the relatives of Captain Benjamin Smith to bury his body subject to several strict requirements:

…Liberty to Inter him in the Common burying place, which is granted by said Council provided that they follow this our order: to wit.

they are to rap his body in a Tarred Sheet, and put him in a Coffin Tared within and without and over that Rap a Tarpoilin and then Remove the Corps out of the house, and put it into another coffin which is to be pitched or tarred within, and then proceed with the Corpes by water to a place called Cold Spring, and from Thence to pass between the Lands of Mr. Winsor and Merrit to the Land of John Whipple to the bureing place. Keeping Equal Distance between the houses of Luther and Dexter the following persons being perposed to attend the funeral and to bury him… they shifting their cloathing properly [after the burial]. [Churchill, 136.]

Conclusion:

By the end of the eighteenth century, inoculation had become widespread with the result that both infection and mortality rates due to smallpox dropped dramatically. While the epidemic of 1721 caused 5,759 infections and 844 deaths in a population of 12,000 in Boston, later outbreaks, such as that in 1778 resulted in only 42 deaths from 122 “natural” cases of smallpox due to the simultaneous inoculation of 2,121 people of whom only 29 died.

New England’s leading role in introducing the practice of inoculation (variolation) in 1721 was followed by a similarly early role in introducing vaccination as developed by Edward Jenner in 1796 in which cowpox virus was used rather than live smallpox virus. In 1799, Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse of Cambridge, Massachusetts, received a paper describing Jenner’s method. A founding professor of the Harvard Medical School in 1782, Waterhouse had formally studied medicine at universities in London, Edinburgh, and Leyden at a time when most of his colleagues acquired an empirical and traditional understanding of medicine through apprenticeship. In 1800, Waterhouse vaccinated his son using cowpox (also called Kine-pox) virus. The success of this procedure led him to vaccinate the remainder of his family shortly thereafter. In an effort to demonstrate the efficacy of this method, Waterhouse sent members of his household to the smallpox hospital in Brookline to be exposed to smallpox virus by Dr. William Aspinwall. The experiment demonstrated conclusively that vaccination conferred immunity to smallpox, and the practice quickly spread, but not without some minor opposition from those who feared that it might carry contagion as variolation had, and through folkloric beliefs or rumors that those vaccinated in this manner might grow hooves or horns.

Sources:

Acts and resolves at the General Assembly of the governor and company of the English colony of Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations in New-England…October 1747 to October 1752. Providence: 19–. Available online, April 2020: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t5p84jd71&view=image&seq=4

Blake, John B. “Benjamin Waterhouse and the Introduction of Vaccination,” Reviews of Infectious Diseases, Vol. 9, No. 5 (Sep. – Oct., 1987), 1044-1052. https://www-jstor-org.camproxy.minlib.net/stable/pdf/4454213.pdf?ab_segments=0%252Fbasic_SYC-5152%252Ftest&refreqid=excelsior%3A0f3ee864383b02fa12ff79c34016df91

Blancou, J. “History of disinfection from early times until the end of the 18th century,” Rev. sci. tech. Off.int. Epiz., 1995, 14(1), 31-39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7548969

Boston Selectmen’s Minutes, 1701-1822 (12 Volumes). Boston: Municipal & City Printing Offices, 1884-1909. Available online, April 2020: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000851987?type%5B%5D=all&lookfor%5B%5D=Boston%20Selectmen%27s%20Minutes&ft=

Boylston, Zabdiel. Dr. Boylston’s Account of the Small-Pox Inoculated in New England. London: S. Chandler, 1726. online: https://archive.org/details/2544007R.nlm.nih.gov/page/n9/mode/2up

Churchill, Donald, MD. “The History of Smallpox in Rhode Island,” The Providence Medical Journal, Vol. III, no. 4 (July 1902).

Connecticut History.Org. “The Pest House Completed.” https://connecticuthistory.org/the-pest-house-completed-today-in-history/

Currier, John J. History of Newbury, Mass. 1635-1902. Boston: Damrell & Upham, 1902.

Currier, John J. History of Newburyport, Mass. Newburyport, Mass.: Published by the author, 1906.

Gavin, Alison M. “The Asylum at Quaise: Nantucket’s Antebellum Poor Farm,” Historic Nantucket, v. 52, no.4 (Fall 2003), 17-20.

Historic American Buildings Survey. Old Gaol, Nantucket, Massachusetts. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh/item/ma0825/

Journals of the House of Representatives, Volumes 1-54, 1717-1779. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, various dates. Available online, April 2020: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000532438.

Kanes, Candace. “Smallpox in Portland,” Maine Historical Society Newsletter, (Fall 2013), 6-7. https://www.mainehistory.org/PDF/newsletter_Fall2013.pdf

Kass, Amelie. “Boston’s Historic Smallpox Epidemic,” The Massachusetts Historical Review, Vol. 14 (2012), 1-51.

Lattimore, Richmond. The Odyssey of Homer. New York: Harper & Row, 1968.

Macy, Obed. The History of Nantucket. Mansfield, Mass: Macy & Pratt, 1880.

Martekathe, Peter. “In Woods of Portland: Smallpox ‘Hospitals’,” Hartford Courant, September 23, 1998. https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-xpm-1998-09-23-9809200033-story.html

Niederhuber, Matthew. “Death Rates from Smallpox in Boston, MA, 1702-1920.” Science in the News. Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. http://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/special-edition-on-infectious-disease/2014/the-fight-over-inoculation-during-the-1721-boston-smallpox-epidemic/

Ottinger, Leslie W. “Sally Takes the Smallpox,” Historic Nantucket, v. 48, no. 4 (Fall 1999), 13-15.

Rainsford Island Chronology. 2009. http://rainsfordisland.blogspot.com/2009/12/histrory-of-rainsford-island-as.html

Shurtleff, Nathaniel B., ed. Records of the Governor and Company of Massachusetts Bay in New England. v. 1 (1642-1649). Boston: William White printer for the Commonwealth, 1853. Available online, April 2020: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.35112104872215&view=image&seq=9

Smallpox – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/transmission/index.html

Spectacle Island Chronology. 2014. http://spectacleislandhistory.blogspot.com/

The Acts & Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, 1692-1780. (Vol. I to XXI) Boston: Wright & Potter, State Printers, various dates 1869-1922. Available online, April 2020: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951p00506895h&view=image&seq=7

Winslow, Ola Elizabeth. A Destroying Angel: The Conquest of Smallpox in Colonial Boston. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1974.

Woodward, Samuel Bayard, MD. “The Story of Smallpox in Massachusetts,” The New England Journal of Medicine, v. 206, No. 23 (June 9, 1932), 1181-1191.

Abbreviations for in-text citations:

BSM – Boston Selectmen’s Minutes

JHR – Journals of the House of Representatives (Massachusetts)

A&RMB – The Acts & Resolves, Public and Private, of the Province of Massachusetts Bay