Historic Masonry Finishes

Although once ubiquitous, exterior masonry finishes have largely been forgotten since the advent of the Industrial Revolution. For thousands of years before the development of inexpensive mechanical power, builders looked to materials close to their buildings sites. Hand tools and craft methods of production employed softer masonry materials that were less uniform in their physical properties than those produced industrially after the mid-nineteenth century. For the most part, these materials were covered with a variety of coatings and finishes to protect them from the weather and to permit the creation of finely finished exteriors.

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, the widespread availability of water and steam power, inexpensive overland transportation by railroad, and advances in engineering introduced inexpensive masonry materials that were both hard enough to withstand weather and that possessed finely finished surfaces intended to be exposed to view. Over the course of the subsequent one and one-half centuries, builders and property owners abandoned old masonry maintenance practices, eventually forgetting their utility and actively removing them in misguided efforts to restore what they incorrectly perceived as original surfaces. As a result, the majority of New England’s pre-industrial masonry buildings – from major monuments to simple houses – have suffered physical damage. In addition, the appearance of most misrepresents our architectural heritage and would be unrecognizable to their builders and historic occupants.

Introduction: Basic Masonry Materials

For thousands of years across regions as diverse as Asia, Europe, the Mid-East and the Americas, masonry buildings were finished and coated with a variety of surface treatments. Among the most common finishes were plaster (essentially lime mortar, now commonly called “stucco” in the USA), mastic (opaque mixtures of linseed oil, fine aggregate and lead oxide or other minerals to speed drying), paint and transparent coatings (linseed oil, waxes, lead paint and iron oxide washes), and the lining out of mortar joints (called tuck pointing in the United Kingdom) to provide the appearance of uniform mortar joints and bricks or ashlar stone. These finishes served an important role in protecting and extending the useful life of the relatively soft and porous materials available to pre-industrial builders.

Building lime (calcium carbonate) was one of the key elements for all masonry construction. Made from burning limestone, marble, oyster shells and other calcareous materials, building lime required both an ample supply of stone or shells and firewood. In New England, where limestone is rare, builders reserved it for use on weathering surfaces. Instead, builders used clay mortars for the cores of walls and chimneys where it would be protected from wind and rain. Both clay and lime mortars were soft, vapor permeable and durable. Unlike modern masonry that seeks to exclude water, they operated as a permeable system that could absorb rainwater across broad surfaces and release it quickly through evaporation. In addition, they allowed vapor to move through walls and evaporate out through mortar joints, thereby reducing condensation and the buildup of moisture in walls. Coatings such as limewash and exterior plaster provided easily renewable, sacrificial layers to protect underlying masonry. These coatings also allowed builders to create more colorful, stylish architectural embellishments than would have been otherwise possible.

In Europe and North America, the advent of harder, more uniform, engineered building materials during the first half of the nineteenth century, and the development of inexpensive rail transport led to the adoption of manufactured building materials for which coatings were not necessary. Gradually, the maintenance of renders, pigmented washes, limewash and paints on older buildings was abandoned and forgotten, although the early materials were tenacious and remain readily visible in early architectural photographs of New England in the 1850s. At the same time nineteenth-century Romanticism began to celebrate the irregular, picturesque qualities of handmade goods and architectural ruins. In England, a large number of would-be restorers began stripping original interior plaster work and colored paint from Gothic cathedrals, creating an aesthetic that celebrated exposed rubble stone and handmade brick. In New England, this movement led the Boston Society of Architects and others influenced by the Arts & Crafts Movement to remove all coatings and color from monuments such as Boston’s Faneuil Hall (1742, 1761, 1806), Newport’s Brick Market (1762), Newport’s Colony House (1741), and many other buildings to expose the buildings’ “honest” handmade brickwork. Today, more than one hundred fifty years later, early finishes continue to cling to many of these buildings in areas sheltered from weather and on mortar joints, even on buildings that have been sandblasted.

Masonry finishes comprise four broad categories, namely:

- Tooled and lined-out joints intended to give a more regular appearance to irregularly shaped masonry materials;

- Transparent coatings: linseed oil, waxes and pigmented washes often applied in conjunction with finely tooled, lined-out mortar joints;

- Opaque coatings: limewashes and paints; and

- Built-up surfaces: renders, plaster and mastic

I. Transparent Coatings & Lined-out Joints:

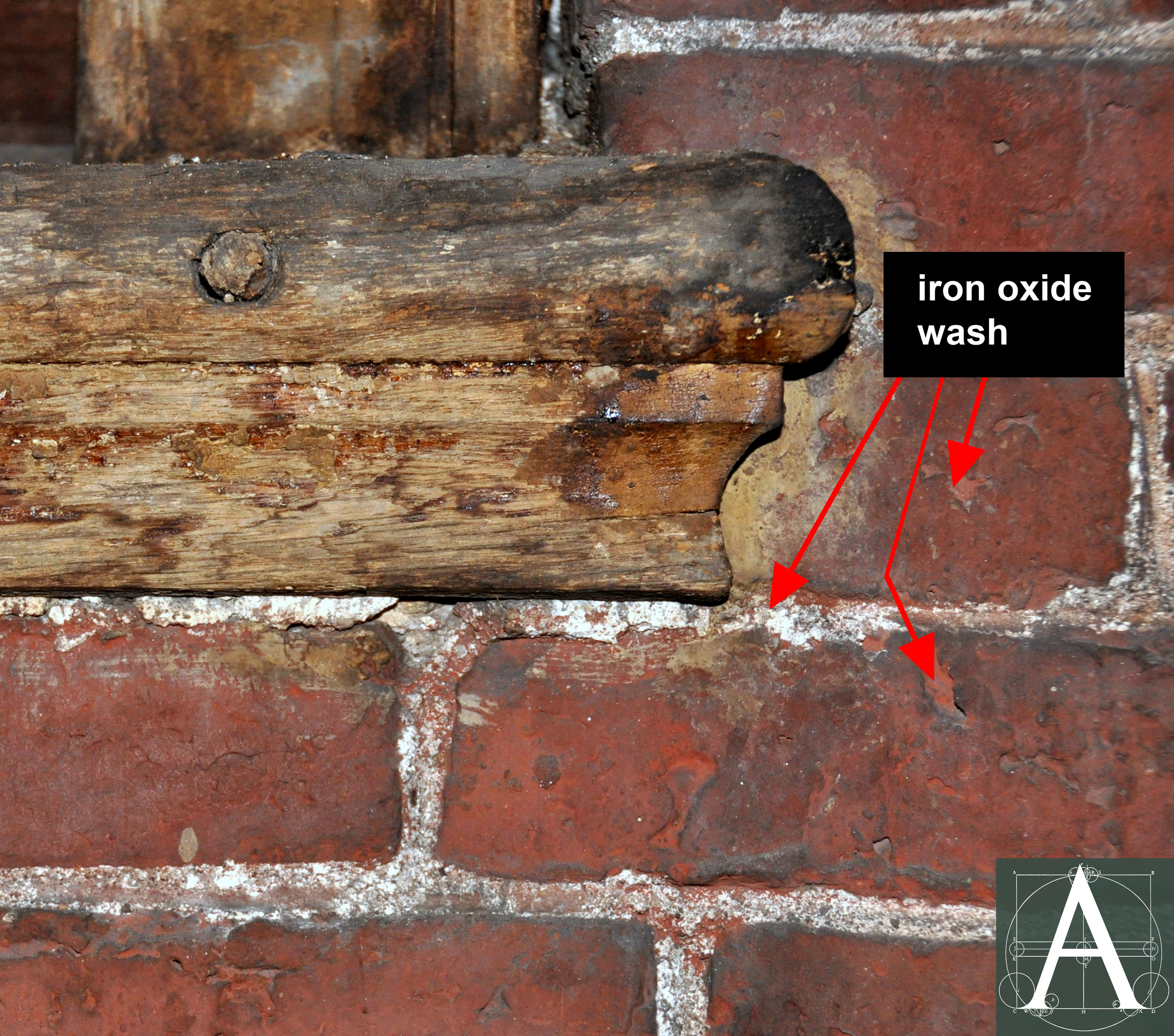

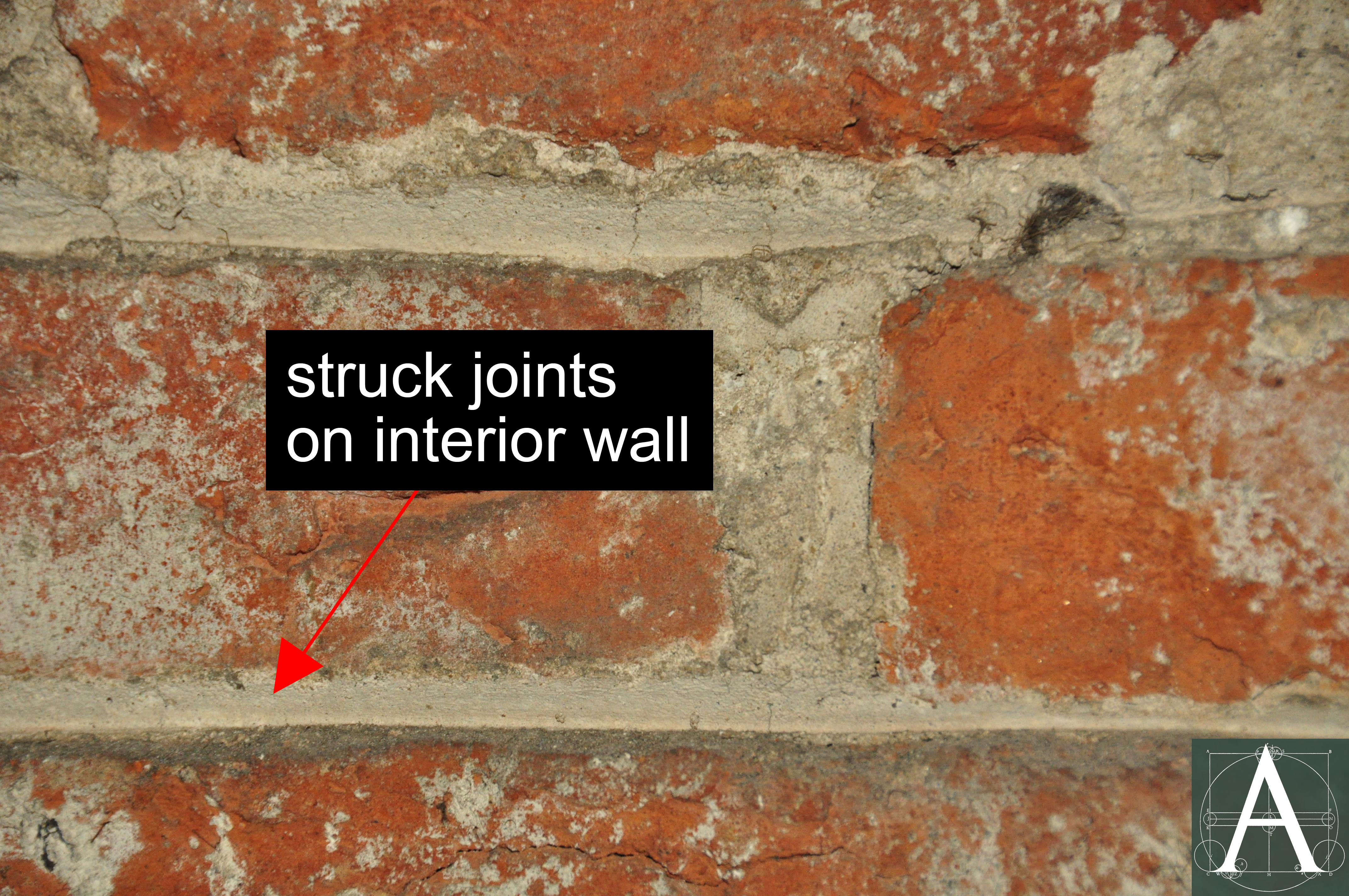

The method by which New England builders most frequently created the appearance of uniformity with handmade common bricks was to strike fine, straight joints in the bedding mortar, creating a precise grid of joint lines. Surviving joints found on façades and finished elevations of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century buildings are predominantly flat-bottomed channels. After joints were tooled, masonry surfaces were washed with a solution containing red iron oxide that soaked into mortar and bricks alike, creating a uniform red color to conceal wide variations in brick color. Joints could then be left without further treatment, their regular shadow lines contributing to creating the illusion of finer brickwork. Examples include the Richard Derby House (1761-62 – Salem, Massachusetts) and, possibly, the Usher-Royall House (ca. 1692, 1733-37 & 1747-50 – Medford, Massachusetts), where mortar joints on the interior faces of ca. 1692 walls have struck profiles despite being covered with plaster from the outset.

Tooled joints on many buildings were often filled with a thin ribbon of white. Joints of this type have not been widely subjected to chemical analysis to determine the composition of the white lining; however, lime putty and white lead are known to have been used in the United Kingdom and continental Europe. Joints of this type are evident on sheltered portions of walls beneath eaves and porches, as at the Cheshire Mill’s Superintendent’s House (1853-63 – Harrisville, New Hampshire).

Richard Derby House – detail of original 1761 mortar joint and evidence of red iron-oxide wash on brickwork concealed from weather by ca. 1810

Usher-Royall House, Medford, Massachusetts – detail of struck mortar joints on interior wall of north parlor (originally plastered)

Cheshire Mills Superintendent’s House – close-up view of masonry showing iron oxide wash applied as base layer before lining-out of joints

Known as tuck pointing in the United Kingdom, this process is largely forgotten in the United States. Some architectural sources still use the term to apply to joints lined white, but the term is now used more commonly in the United States to refer to tooled joints without added white lines.

Traditional tuck pointing derives from European practice that was widespread by the seventeenth century:

Tuck pointing in England probably evolved from continental influence during the late 17th century, where it is to be seen in the Netherlands, Flanders and parts of France, such as Normandy. It was certainly well established by the early 18th century, being then referred to in Batty Langley’s d.1745 price book for London builders; and then referred to as ‘Tuck and Pat’ work. It was reserved for use on premier facades, or ‘showfaces’, of properties, the majority of which were also given a ‘colour wash’, consisting of an ochre, dissolved in water containing a fixative, or mordant, in order to unify varying tones of handmade bricks. (Gerard Lynch, The Red Mason.)

This practice can be seen on buildings of the late eighteenth century such as #4 & 5 Spanish Place in London where two houses built ca. 1780-90 in the development of the Duke of Manchester’s estate show the weathered condition of the buildings’ yellow brick (#4) and the restored condition with pigment providing a uniform base color and joints lined carefully with white (#5).

(left to right) #5 & 4 Spanish Place, London – detail of weathered original brickwork (right) and restored brickwork with pigmented surfaces and lined-out (tuck-pointed) joints (left)

In The Bostonians, Henry James writes of events in the mid-1870s and describes a similar treatment on rowhouses from the 1820s-1830s:

The sitting room, beside it, was slightly larger, and they both commanded [a view of] a row of tenements no less degenerate than Ransom’s own habitation – houses built forty years before, and already sere and superannuated. These were also painted red, and the bricks were accentuated by a white line… (H. James. The Bostonians. 190)

Similar pointing appears on some stone masonry buildings, such as Cheshire Mill #1 (1846 – Harrisville, New Hampshire) and the Frost Free Library (1866 – Marlborough, New Hampshire), where pointing mortar made of natural cement was scored and filled with white to give the appearance of much finer ashlar than could be made from the split-faced granite of which the buildings were constructed. This detail was used on the façade and side elevations of both buildings; however, the rear (north) elevation of Mill #1 was constructed of granite rubble with flush joints that were left untooled, while the rear (south) elevation of the Frost Free Library was constructed of coursed split granite, the curved and irregular joints of which were lined out.

Cheshire Mill #1 – detail of mortar joints pointed with natural cement, ruled and lined out in white

Frost Free Library, Marlborough, New Hampshire – lined-out mortar joints at window heads on the west elevation [image with permission from the Frost Free Library]

Irregular mortar joints lined-out in white on south gable [image with permission from the Frost Free Library]

Three-family houses such as Mary Sullivan Three-Decker (ca. 1900 – 52 Francis Street, Boston) stands on a foundation of Roxbury Puddingstone laid in coursed rubble (perhaps quarried on-site or nearby) on which the thick irregular mortar joints have been lined-out in white to give the appearance of random ashlar. Similar details exist at the Hilma Olsson Two-Family House (ca. 1900 – 36 Fenwood Road, Boston) except that mortar joints are beaded and not tinted. The mortar has a color similar to that of natural cement, which it may be. Several buildings in the group have mortar joints lined out in red, as seen at the James F. Lowney Two-Family House (ca. 1900 – 32 Fenwood Road, Boston) where original mortar joints were grooved on both sides to enhance the straightness of their appearance. In some cases, mortar was spread over stone faces with mortar joints scored across them, thereby adding to the regularity of their appearance.

52 Francis Street, Boston, Massachusetts (ca. 1900) – detail of mortar joints lined out in white to give appearance of random ashlar to random rubble

36 Fenwood Road, Boston, Massachusetts (ca. 1900) – detail of beaded mortar joints and mortar applied over stone faces to create the appearance of random ashlar

32 Fenwood Road, Boston, Massachusetts (ca. 1900) – detail of joints scored and tinted red to create the appearance of random ashlar on a random rubble wall

Transparent Coatings

Wax and oil are mentioned as coatings in various histories; however, no systematic examination of buildings has been conducted to test for the presence of these materials. [Information needed.] Massachusetts Hall (1719 – Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts) and the other brick buildings standing around Harvard Yard were “carefully pointed and oiled with two coats of oil into which a little Venetian red had been stirred” during the summer of 1871 in the belief that “the buildings will thus be better preserved from the weather, and they will be drier and warmer, as well as better looking.” (Harvard Annual Reports: President’s Report. 1870-71: 77.) This treatment for brick buildings was described in 1864 by Calvert Vaux in Villas and Cottages: “A coat of boiled oil has a good effect where more expensive face-brick are used, both in hardening the surface and equalizing the tint.” (Calvert Vaux. Villas and Cottages. 38.) It is not clear if this treatment was applied to Massachusetts Hall as a Victorian effort to unify the color of its early eighteenth-century brickwork or as part of the building’s traditional maintenance.

II. Opaque Coatings

Prior to 1800, limewash, whitewash and paint were once so common that the majority of the region’s private residences and major public buildings are shown in this condition in early architectural photographs. Views from the 1850s show a high proportion of coatings eroded due to a lack of maintenance. In town centers where residential neighborhoods were being transformed into commercial districts, many buildings were re-coated with large advertising signs painted across their façades. Aggressively advertising may eventually have contributed to a widespread belief that coating brick and masonry was a modern commercial alteration that concealed materials which original builders intended to expose.

Physical and photographic evidence of early masonry coatings abounds, but evidence in the form of building contracts and specifications is rare, in part because such documents are rare, and in part because it may have seemed too ordinary a treatment to warrant a separate specification.

Among the earliest surviving evidence for coating masonry with limewash is the former west gable elevation of the Spencer-Peirce-Little House (ca. 1690 – Newbury, Massachusetts). Concealed by a wood-frame addition in 1796, the entire two and one-half storeys of this wall preserves its coating of white limewash, which is visible in the attic and in view ports opened at former window embrasures. The thickness of this coating and its grainy/pebbled texture at blind window arches suggests it was renewed several times and that the limewash was bulked-out with sand. All surfaces appear to have been left the natural white created by the limewash’s calcium carbonate. Surviving overpainting at the window frames of the attic and first storey indicate a layer of red paint or limewash was applied to the window surrounds and sash.

Spencer-Peirce-Little House, 5 Little’s Lane, Newbury, Massachusetts – ca.1690 – showing remnants of several generations of coating on masonry façade; renewed limewash on east gable end [Image with permission from Historic New England]

Spencer-Peirce-Little House – west gable showing full coating with limewash protected from weather after construction of the house’s 1796 west wing [Image with permission from Historic New England]

Spencer-Peirce-Little House – former west elevation – detail of a first-storey arched window head with plaster and limewash within a blind arch and limewash on brickwork at the top of the arch – concealed by 1796 addition [Image with permission from Historic New England]

Building contracts for the Thomas Hancock House (1737; demolished 1863 – Boston, Massachusetts), one of the most lavish and expensive houses of its era, record the building’s construction with “local ‘Mistick or Medford Stone’ for walls and imported Connecticut brownstone for trim.” (A.L. Cummings and R. Candee. 25.) Surviving historic photographs of the building show the façade constructed of what appears to be granite ashlar; the stones bore hammered finishes and were carefully laid in a formal pattern resembling Flemish bond in brickwork with symmetrically placed closers. The low porosity of granite, which makes it difficult to secure good adhesion of coatings, and the formality of the building’s ashlar suggest the stone may have been intended to be left exposed; however, its brown sandstone trimmings appear to have been coated. Cummings and Candee observe that a fireboard of 1700s shows the quoins painted white “perhaps to suggest a lighter stone color or attempt to control brownstone decay.” (A.L. Cummings and R. Candee. 25.) Similarly, a view of the house painted by Charles Furneaux around 1859 depicts the body of the building as dark gray, approximating the color of granite, with finely dressed trimmings in a light cream/white color to match the color of painted woodwork at the main entry and dormers.

Among the many major buildings of the eighteenth century that bore opaque painted finishes in their earliest documented appearances are:

- Jonathan Wade House (1683-89 – Medford, Massachusetts)

- Old State House (1712 – Boston, Massachusetts)

- The Colony House (1741 – Newport, Rhode Island)

- Faneuil Hall (1742, 1761, 1806 – Boston, Massachusetts)

- The Brick Market (1762 – Newport, Rhode Island)

- Touro Synagogue (1763 – Newport, Rhode Island)

Neglect of these coatings began by the mid-nineteenth century, when harder, more uniformly fabricated masonry materials became widely available. By 1864, architectural writers like Calvert Vaux (Cottages and Villas, 1864) recommended leaving brickwork exposed if “the materials are good and the color [of the bricks] is not over red….and the annoyance and expense of lime-washing or painting every year or two would be avoided.” (Calvert Vaux. 77.) Early photographs of the Spencer-Peirce-Little House are typical in showing large patches of limewash still adhering to masonry, but weathered away from much of the wall’s surface during this period.

The late nineteenth century saw the active removal of coatings. Fueled in part by the Romantic Movement and its aggressive, fanciful and misinformed restorations of medieval churches in England, the impetus to remove coatings from early buildings in New England was driven by the Arts and Crafts Movement and its misguided belief that rough and less-refined materials contained in early masonry buildings represented their original appearance and the “honest” crafts of the past. Like its English counterpart that stripped medieval churches of their original plaster and painted surfaces to expose rough stonework, New England restorers exposed soft, irregular brickwork and were surprised by the consequent deterioration of the exposed bricks. By the early 1920s, the Boston Society of Architects played a role in this effort by recommending “that the outside walls [of Faneuil Hall] be treated with sandblast to remove all paint to restore bricks to their original color…” (R. Detwiller. 49) By the time Faneuil Hall was stripped of its paint, Old North Church (1723 – Boston, Massachusetts), the Old State House (1711 – Boston, Massachusetts) and the Old South Meetinghouse (1729 – Boston, Massachusetts) had all been stripped of their coatings with a destructive mixture of sandblasting and lye.

Except for a small number of antiquarians, few gave any thought to the possibility that these coatings may have been original. On March 28, 1925, William Sumner Appleton, founder of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (now Historic New England), wrote to the architectural firm of Densmore, LeClear & Robbins, which had been engaged to restore the Pacific National Bank (1818 – Nantucket, Massachusetts). Having heard from friends on island that paint removal was being planned for the bank’s exceptionally fine Federal-style building at the head of the town’s main square, Appleton wrote:

I hope you won’t mind my writing to you as a total stranger to urge you to go slowly in this matter of paint removal. I have an impression that it was by no means intended that all the buildings erected at about the time of this bank should be of natural colored brick, and am rather inclined to agree with the architects who tell me that many of these buildings were always intended to be painted. At all events, be that as it may, the color scheme of the Pacific Bank Building has always rather appealed to me, partly because of its being quiet and unobtrusive and partly because it helped set off the architectural lines of the building. (Appleton, William Sumner. Letter to Densmore, LeClear & Robbins, March 28, 1925.)

Like Faneuil Hall and the former Rotch Market House now known as the Pacific Club (1772, Nantucket, Massachusetts), the bank was covered at the time of paint removal with a coating tinted with yellow ochre to resemble the soft color of English Portland stone. Brownstone trimmings were either picked out in a contrasting brown of similar shade to the underlying stone, or left unpainted. Earlier historic photographs of ca. 1860 show the building painted a dark color, presumably a brick tone, with brownstone trimming picked out in a light color.

The restoration of the Brick Market (1762 – Newport, Rhode Island) took place in two phases under the supervision of Norman Isham, a leading preservation architect of the early twentieth century. As early as 1928 following repairs conducted well before the paint’s removal, Isham commented that “Unfortunately, the basement story was constructed of such soft brick that, except for the west side and south walls, it had to be replaced.” (Downing & Scully. 84.) When the building’s new tenant, the Newport Chamber of Commerce, wrote in 1936 to John Nicholas Brown, the building’s owner, in the hope of having exterior paint removed, Brown explained in a letter to Isham:

I have written them that we decided at the time of the restoration not to remove the paint (1) because the brick was porous and seemed to need a coating of paint for water-proofing and (2) in order to hide the difference in colour between the old and new. (A. Lozupone. 51.)

In a subsequent letter to the Newport Chamber of Commerce, Brown noted that “Mr. Isham also felt that paint had been used originally on the building.” (A. Lozupone. 51.) Nonetheless, the coatings were removed, and the building stripped of its strongly classical appearance once its Ionic pilasters, deep entablature and eared window cases were surrounded by rough brick rather than a uniform stone color. Also exposed by paint removal were wooden nailing blocks coursed into the brickwork and protected from weather as well as concealed from view by the same paint as surrounding brickwork. Aside from altering the building’s intended appearance, this removal hastened deterioration of soft brick.

Brick Market (1762) 127 Thames Street, Newport, Rhode Island – 1937 view showing painted surfaces remaining in place (HABS, A. LeBoeuf, photographer)

1982 view of the Brick Market showing wooden nailers coursed into brickwork to allow attachment of window cases

1982 view of the Brick Market showing the extent of damage to soft-fired bricks exposed to the weather

Sanded Paint

Sand was frequently mixed into oil paints and limewashes or applied to the surface of wet paint as an economical way to enhance the stone-like appearance of the masonry. The David Sears House (1842, Brookline, Massachusetts) was designed by Edward Shaw, who illustrated it as Plates 47 & 48 in The Modern Architect. Although built for a wealthy merchant as a country seat on a 200-acre property, the house’s brickwork was painted and sanded upon completion. In a clear effort to economize, Shaw’s Manchester Town Hall (1844-1845 – Manchester, New Hampshire) was faced with brick and painted upon completion although originally planned for granite facings:

The design of the architect was that the building should have been entirely of stone, the columns hammered and the wall of ashlar work, but the committee deviated from his plans and the building is of stone and brick, painted and sanded to imitate stone… (E. Shaw. ix.)

It is likely that many buildings were painted in this manner, but they have not been systematically documented.

III. Built-Up Coatings

Some masonry and even timber buildings were coated with mortar to provide a layer of weather protection and resistance to the spread of fire. Since lime mortar and plaster have nearly the same composition, historical sources in New England frequently refer to this material as “plaster.” although it bears other names, including roughcast, pargeting and render (primarily British).

Roughcast:

Roughcast and related names such as “harling” (Scottish, from the verb “to hurl”) and “pargetting” also “pargeting” and “parging” (from the French “par jeter” meaning “to throw all over”) arise from the technique by which this mortar was applied. By throwing the mortar at a prepared wall, masons believed that more of the material was forced into the crevices and pores of the substrate, creating greater adhesion. While in England, much of the mortar applied in this manner was frequently left with a pebbly surface, surviving examples in New England were more commonly troweled smooth and occasionally decorated with patterns. The Old Feather Store (1680, demolished 1860, Boston, Massachusetts), was finished with a quoin-like pattern of troweled surfaces at its gable rakes, and the end gable bore a date panel troweled into the roughcast. Flat areas of the walls had broken glass pressed into their surfaces to create more reflectivity and color. It is likely that this material was more widely used in Boston and densely built towns during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in part for fire resistance; however, so few examples remain in New England that it is not possible to generalize about its use. Additional examples of the technique and material survive on chimney flues, such as those at the Matthew Perkins House (1701 – Ipswich, Massachusetts) which were pargeted with a mixture of clay, fiber and some lime.

Old Feather Store, Boston – built 1680, demolished 1860 – showing exterior plaster [Image courtesy of Historic New England]

Troweled and Finished Plaster/Render

From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, both timber and masonry buildings were covered with external plaster/render, which was troweled or floated to a smooth surface and then scored and/or painted with false mortar joints to give the appearance of ashlar. Applications of this sort were observed in New Haven, Connecticut, between 1796 and 1808 by Timothy Dwight, President of Yale College, in his Travels Through New England and New York:

Most of the buildings are of wood and may be considered as destined to become the fuel of a future conflagration. Building with brick and stone is, however, becoming more and more frequent. The mode of building with stone, which seems not unlikely to become general, is to raise walls of whinstone, broken into fragments of every irregular form, laid in a strong mortar, and then to overcast them with a peculiar species of cement.

The corners, frames of the doors, arches and sills of the windows, cornices and other ornamental parts are of a sprightly colored freestone. The cement is sometimes divided by lines at right angles in such a manner as to make the whole resemble a building of marble; and, being smooth and white, is of course very handsome. Several valuable houses have been lately built in this manner; and the cement, contrary to the general expectation, has hitherto perfectly sustained the severity of our seasons. (T. Dwight. 153-154.)

For timber buildings, plaster provided protection from weather, as it did for masonry buildings where it reduced the absorption of water from wind-driven rain. In his architectural pattern book, The Modern Architect (1854), Edward Shaw noted the effect of external plaster, which he also called “cement.” Shaw observed:

The idea in regard to the thickness of walls of buildings left without cement, namely, that the exterior wall should be eight inches instead of four inches, was not advanced, in consideration that the cement would impart to the wall a strength which would not exist without it, but comes from the fact that water will pass through the joints of a four-inch wall in a storm, and the extra four inches are needed to remedy a defect that would not exist in a wall covered with cement. (E. Shaw. 117.)

Early surviving examples are rare. Notable among those that remain are the Hooper-Lee-Nichols House (1685, 1733 & 1758, Cambridge, Massachusetts) a timber-frame house on which the west gable end retains a wall of ashlar render installed on wooden lath in 1758, although subsequently heavily patched with additional skim coats of plaster. The timber-frame Pellet-Barrett House (1728 – Concord, Massachusetts) has a similar render believed to have been installed in 1728 (but not documented) extending across the entirety of its façade. Fragments of exterior plaster painted to resemble brickwork remain on a former west gable of the Jonathan & Simon Hosmer House (1760 – Acton, Massachusetts), which was enclosed by an addition in 1796-97.

Both the Samuel Chase House (1713, West Newbury, Massachusetts) and the Robert Peaslee House, a/k/a the Joseph Peaslee House or the Peaslee Garrison (1707-14, Haverhill, Massachusetts) are brick buildings, the façades of which were rendered and scored to resemble ashlar with cambered window arches in a naïve interpretation of Georgian architectural fashion.

Samuel Chase House – detail of plastered façade (rendered) scored as ashlar with cambered window arches (pre-1985); plaster removed ca. 1985

Peaslee Garrison House ca. 1890-1910 – showing rendered facade with scoring lines to resemble ashlar faintly visible [image courtesy of Historic New England]

John Angier House (1842), Medford, Massachusetts – Alexander Jackson Davis, architect – façade rendered to resemble finely cut ashlar

John Angier House – detail of original render and scored false mortar joints in sheltered locations beneath the eaves

Similarly scored plaster was applied to the Manchester City Hall (1844, Manchester, New Hampshire – Edward Shaw, architect) as a cost-saving measure to replace the granite ashlar that was originally specified for the structure. In addition to masonry buildings, many wood-frame buildings were finished with exterior plaster, such as Trinity Episcopal Church (1839, burned 1846, Nantucket, Massachusetts) where a pre-existing timber-frame Quaker Meeting House was reconfigured to make a church:

The tower, which is of a square form throughout, is about 80 feet in height and is composed of very heavy timber, the upper portion finished with wood work, and the lower, together with the main body of the building, coated with plaster and Roman cement; the whole covered with a mixture of paint and sand, colored to resemble granite, of which it is a most admirable and perfect imitation. (Inquirer & Mirror. September 14, 1839, 2-3.)

Many examples remain throughout the region in partial or complete form, but largely unrecognized beneath modern cement repairs and paints.

MASTIC

Sources

Appleton, William Sumner. Letter to Densmore, LeClear & Robbins, March 28, 1925. Appleton Correspondence: Pacific Bank. Historic New England Archives, microfiche.

Cummings, Abbott Lowell and R. Candee. “Colonial and Federal America: Accounts of Early Painting Practices.” In Paint in America: the Colors of Historic Buildings, edited by Roger Moss. Washington, DC: The Preservation Press, 1994.

Detwiller, Frederick and SPNEA Consulting Services Group. “Historic Structure Report: Faneuil Hall” (unpublished report prepared for the National Park Service, 1977).

Downing, Antoinette and Vincent Scully. The Architectural Heritage of Newport, Rhode Island. American Legacy Press, 1982.

Dwight, Timothy. Travels in New-England and New-York. Vol. 1. London: Printed for William Baynes and Son,1823. [Internet Archive: https://ia600705.us.archive.org/0/items/travelsinnewengl01unse/travelsinnewengl01unse.pdf]

Harvard Annual Reports: President’s Report, 1870-71.

Inquirer & Mirror. Nantucket, September 14, 1839, 2-3.

James, Henry. The Bostonians. New York: Modern Library, 1956.

Lounsbury, Carl R. An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Lozupone, Alyssa. “Norman Morrison Isham: Newport Restoration Foreshadows Modern Preservation.” Senior Thesis, Salve Regina University, December, 2010.

Lynch, Gerard. Brickwork: History, Technology and Practice, Volume 1. London: Donhead Publishing, Ltd., 1994.

National Park Service: Preservation Brief 2: Repointing Mortar Joints in Historic Masonry Buildings. https://www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/briefs/2-repoint-mortar-joints.htm

The Red Mason. Website of Gerard Lynch. http://www.brickmaster.co.uk/

Sartre, Josiane. Châteaux « brique et pierre » en France. Paris : Nouvelles Editions Latine, 1981.

Shaw, Edward. The Modern Architect. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1995 reprint of 1854 edition.

Vaux, Calvert. Villas and Cottages. New York: Dover Publishing Co. 1970, reprint of 1864 edition.

Wikipedia: Tuckpointing. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tuckpointing