Notable Elements

- Painted exterior masonry with possible early color [Exterior]

- Skived clapboards with scarf joints [Exterior]

- Characteristic brick-end Federal-period floor plan [Building Type]

- Two cooking hearths & characteristic chimney supports [Chimneys]

- Bricks showing characteristic damage from modern sandblasting [Exterior]

History

Built on a property occupied by descendants of Japhet Turner and Hannah Hudson Turner from 1688 until 1846, the Paul Turner House seems likely to have been constructed for Paul Sampson Turner (1795-1841), the fourth generation of the family to occupy a portion of the property after the water privilege previously used by the family for a sawmill and gristmill had been sold to a cotton and woolen manufacturer in 1814. Local tradition reports that the first formal call for American Independence (the Pembroke Resolves) was drawn up here in 1772 with John Turner serving as the chairman of the drafting committee; however, physical evidence contained in the style and construction methods of the house does not support this building as the location of this event. It is possible that the earlier timbers were used as salvage in building portions of the rear ell or the now demolished barn wing, but the house appears to have been built in a single campaign in the late Federal style. Following the death of Paul Sampson Turner, the house was sold out of the Turner Family in 1846.

Date

1820-25; ca. 1880; ca. 1910-1930

Builder/Architect

unknown

Building Type

Brick-end Federal-style house: The house is composed of a rectangular main block (36’ x 17’) enclosed by a low hip roof with a floor plan that is one room deep with a single room set symmetrically on either side of a central hallway at the first and second storeys. Narrow end walls are made of brick into which chimneys and fireplaces have been built, while front and rear walls are of timber-frame construction covered with clapboards. This floor plan was popular from the 1790s through the 1830s in New England; brick-end versions of it are disproportionately found in Plymouth County, south of Boston. [information needed]

Attached to the rear wall is a wood-frame ell containing a kitchen, service rooms, a former connection to a barn, and smaller chambers at the second storey. The roof line of the rear ell was originally a shed roof that was raised at a later date to the same height as the roof of the main block.

Foundation

Rubble stone below grade capped with blocks of quarried rock-faced granite above grade

Frame

The structure is timber-frame with mortise-and-tenon joinery; brick bearing walls exist only at the end walls of the main house

Chimneys

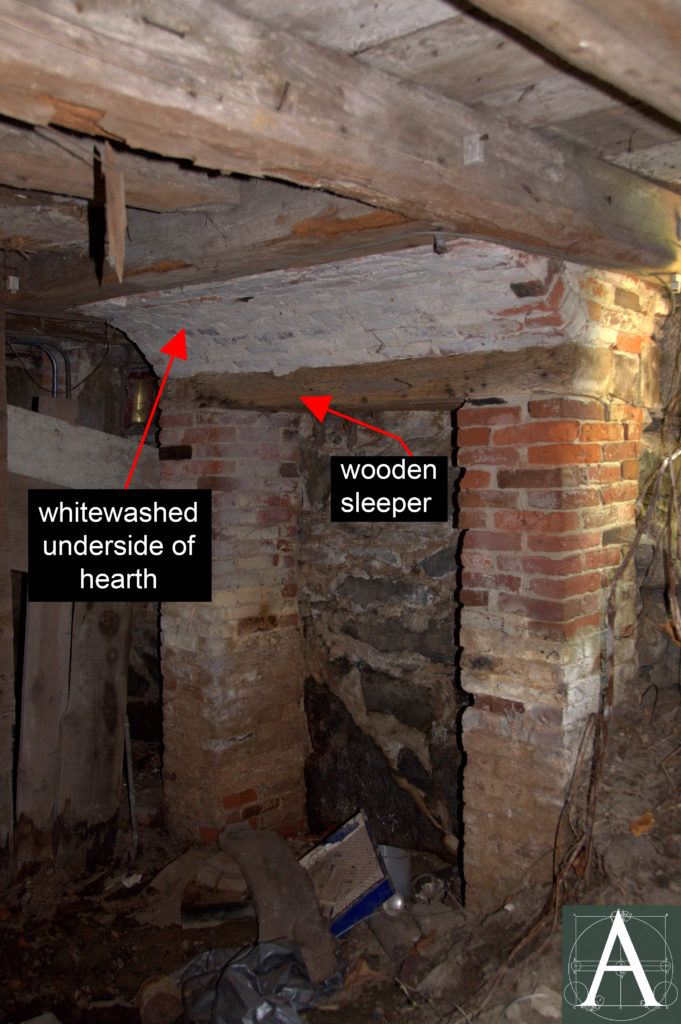

One chimney rises at the center of each brick end wall at the main block of the house. Each of these chimneys rises from a base of two brick piers that support wooden sleepers above which the chimney rises two storeys with one fireplace per storey. First-storey hearths are visible at the cellar and consist of shallow brick arches that extend from the wooden sleepers to a framed header that supports the outer edge of the arch.

A third chimney rises from the rear wall of the ell. At the cellar, this chimney contains a former cooking hearth that has been severely damaged and closed by a concrete-block partition. No bake oven is visible, although it is probable that one existed. Cellar cooking hearths are uncommon, although not rare [information needed]. At the first storey, the chimney has a cooking hearth with a domed brick bake oven that is closed by a cast-iron door surmounted by an iron bar to adjust the damper for the bake-oven flue. The door’s cast fan decoration is characteristic of bake-oven doors from the first half of the nineteenth century. Originally, the chimney ended slightly above the first-storey eaves at the rear ell’s original roofline. The chimney was extended without additional fireplaces above the second-storey eaves when the ell’s roof was raised to match the height of the main house.

Exterior

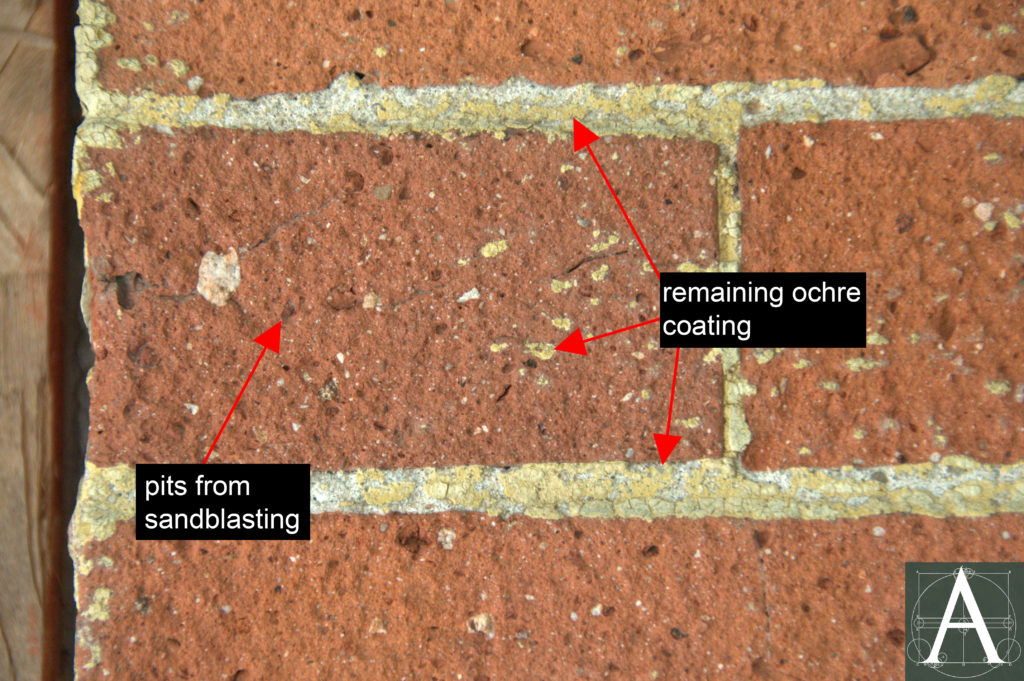

The main block of the house preserves several notable exterior details, most prominently its brick end walls laid in common bond composed of nine rows of headers to each row of alternating stretchers and headers. The bricks of both end walls have been badly pitted by sandblasting to remove masonry coatings. Undisturbed layers of masonry coatings remain concealed by the roof structure of the north porch, which was added between 1910 and 1930. Although the composition and dates of these coatings has not been analyzed, the ochre color of the top layer is similar to colors in use in the early nineteenth century and may represent an original treatment updated by subsequent re-coating with paint or limewash. Ochre pigment remains in the pores and mortar joints of sandblasted bricks as well.

Close up of sand-blasted bricks showing damage to fired surfaces and surviving evidence of ochre-colored coating

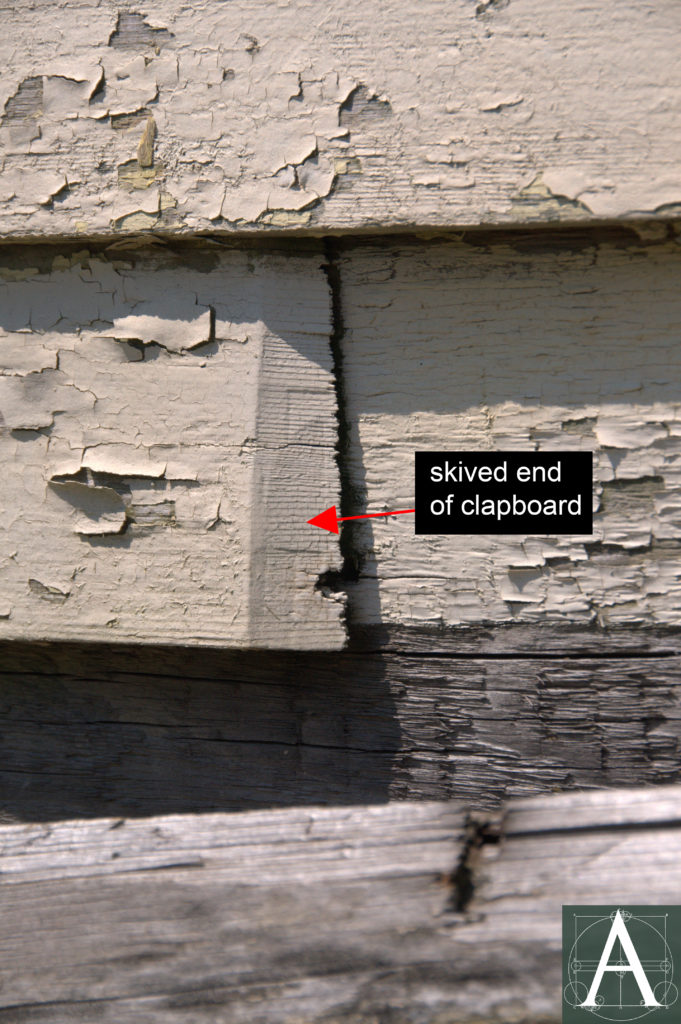

The facade has been altered by the lengthening of its original first-storey windows (ca. 1880-1900) but retains several characteristic details of pre-1850 woodwork finishes. Clapboard ends are skived and lapped in a scarf joint rather than butted together as became common practice in the second half of the nineteenth century. At the base of the facade, the wall is trimmed with a projecting water table, the top of which is beveled to drain water; a shallow tongue of wood at the top of the water table extends up behind clapboards to seal the joint between these two finishes.

Roof

The main roof is a shallow hip supported by a heavy timber frame with one post let into a girt at each end of the hip and diagonal rafters extending from each post to the building’s nearest corners. All slopes of the roof are supported by evenly spaced rafters without purlins.

Interior

Although heavily vandalized and partially demolished, the interior retains a characteristic pillar newel and railing supported by dowel balusters at the center stair hall. Five fireplaces remain in position, three of which preserve transitional Federal/Greek Revival-style mantelpieces. The fireplace at the north chamber preserves fragments of plaster painted to resemble brick at the face of the firebox. The details of the surviving paint are roughly executed, but it is possible that this feature represents the repainting of an earlier masonry coating, or even a roughly executed original treatment.

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian; Michael Burrey, timber-frame carpenter

Sources

Massachusetts Historical Commission: http://mhc-macris.net/Details.aspx?MhcId=PEM.49 [NOTE: property address in historical survey is inaccurately cited.]

Unpublished conditions assessment conducted by Michael Burrey & Brian Pfeiffer, 2013.