Notable Elements

- Early masonry construction with evidence of original coatings [Exterior]

- High-style classical exterior [History]

- Rare building type – market hall – with documentation [History & Building Type]

History

The Brick Market was built in 1760-62 on land granted to the Town of Newport by the Proprietors of Long Wharf upon the condition that it be used “for erecting a Market House.” The grant stipulated that:

…the upper part [of the Market House] be divided into stores for dry-goods, and let out to be the best advantage; and all the rents thereof, together with all the profits that shall arise on said building, shall be lodged in the Town Treasury of said town of Newport, towards a stock for purchasing grain for supplying a Public Granary forever, – built to a plan agreeable to the Proprietors to be estimated at £24,000 old tenor to be raised by lottery……The lower part thereof for a Market House, and for no other use whatsoever, forever; (unless it shall be found convenient to appropriate some part of it for a watch-house). A handsome brick building to be thirty-three feet in front, or in width, and about sixty six feet in length.

Details of the building’s actual construction appear not to have been recorded; however its attribution to Peter Harrison, architect, is secure. The Proprietors of Long Wharf recorded that they appointed a committee “to wait on Capt. Peter Harrison with a plan of the lot…..and advise with him in respect to erecting thereon a Market House. Generally regarded as New England’s first professionally trained architect, Peter Harrison (1716-1775) studied architecture in England and participated in a tour of Italy, which gave him greater fluency in Palladian classicism than any other builder or designer in eighteenth-century New England.

The location of the Market House follows a pattern seen in other large coastal communities, namely that it was placed close to the harbor and wharves to receive goods that were more easily shipped by water than by land in the era before railroads. Market Houses financed by lottery and public subscription were built in similar locations at Boston, Massachusetts (Faneuil Hall – 1742, 1761 & 1806) and Newburyport, Massachusetts (Newburyport Market House – 1823-25), and at Providence, Rhode Island (Providence Market House – 1773, 1797).

Following the building’s construction, the ground floor remained in use for market stalls well into the mid-nineteenth century; however the upper floors were converted from dry-goods storage and a granary to a theatre in 1793. This alteration may have required the removal and reconstruction of floor framing at the upper storey. In 1801, the Town Meeting voted “to build a Stall on the South side of the Brick Market House, in said Market for the use of the Country People who choose to go there, and that said Shall be not let or occupied by the Inhabitants of the Town.” Later in 1801, the Town voted to have “the Brick Market House whitewashed on the inside.”

In 1842, the Town of Newport voted to create a town hall in the former granary and theatre space. Work was done under the supervision of “Mr. Douglas” at a cost of slightly more than $2,000, after which the upper two floors became a single hall 28’ x 61’ x 18’ with galleries on three sides of the room. The building remained in active use as the Town Hall of Newport until 1900 after which the building suffered neglect and deterioration.

In 1914, William Sumner Appleton, founder of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA – now Historic New England), and Mrs. F. E. Chadwick, Rhode Island Vice-President of SPNEA, brought attention to the building and engaged Norman Isham, architect, to undertake an assessment of the building’s condition, which he did in 1916 after which the building’s roof was replaced and its exterior painted.

In 1928, the building was acquired by John Nicholas Brown II, with the goal of commissioning the building’s restoration. Brown re-engaged Isham who carried out a major program of restoration in 1928-30.

Dates

1760-62 (initial construction); 1793 (conversion to theater); 1842 (conversion to Town Hall); 1916 (partial repair/restoration); 1928-30 (restoration)

Builder/Architect

Peter Harrison, architect (1760-62); unknown (1793); superintendence by “Mr. Douglas” (1842); Norman Isham, architect (1916 & 1928-30)

Building Type

Market Hall – The building’s rectangular plan, three-bay width and arcaded first storey follows a pattern for market halls that developed in England from the Middle Ages. Sometimes consisting only of covered stalls at ground level and open to the weather, the building type also expanded to contain a public assembly hall or storage space on upper floors. The relative rarity of the building in New England is a reflection of the region’s predominantly rural character during its first two centuries, during which only a handful of coastal communities were large enough to support market halls.

Foundation

Frame

Exterior

The building’s classical exterior is among the finest of its type surviving in New England. The building’s design is organized as an arcaded basement that serves as a plinth for a two-storey colonnade of wooden Ionic pilasters that rise to a wide entablature at the eaves. Between pilasters, oversized windows at the second storey are set in architraves capped with alternating triangular and segmental pediments. Third-storey windows are set in eared frames. Brickwork at the ground storey is laid in common bond of rows of headers alternating with three rows of stretchers. Upper floors are laid in Flemish bond.

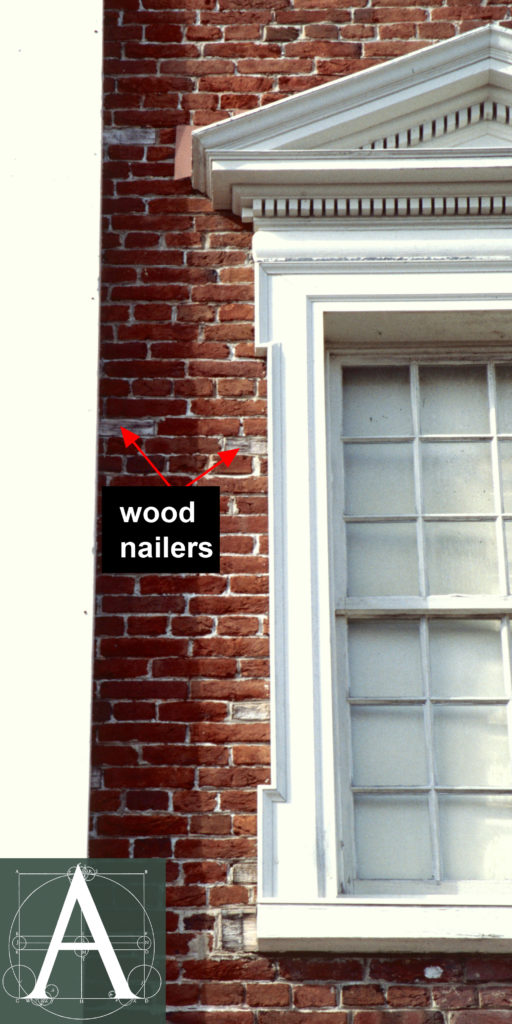

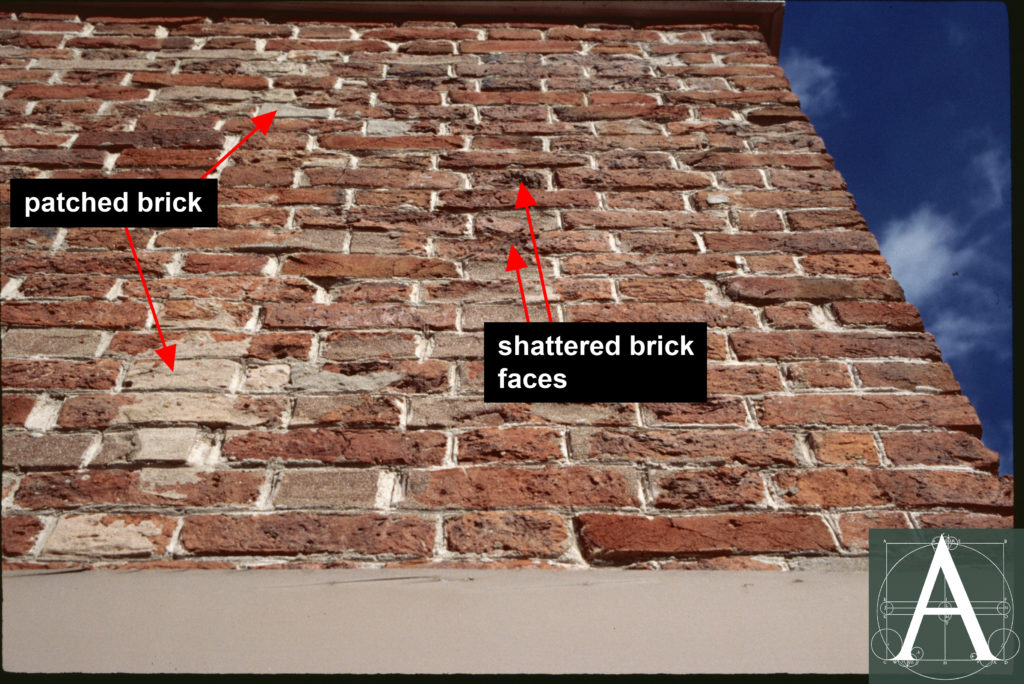

Despite removal of exterior coatings, extensive physical evidence of their presence remains. Wooden window surrounds and wooden pilasters are fastened to masonry through a series of wooden nailers that have been cut to the sizes of bricks and coursed into the brickwork immediately adjoining the frames and pilasters. Now exposed to the weather, these wooden blocks would almost certainly have been coated with paint or other covering both to protect them from decay and to provide a uniform appearance with the surrounding brickwork into which they have been so carefully fitted. In addition, bricks on all elevations of the building have been extensively damaged and patched. As one of the goals of masonry coatings was to protect soft, handmade bricks from weather, much of this damage appears to be the result of the removal of coatings. Another goal of coating was to provide a more uniform surface appearance than was achievable with handmade bricks fired in small kilns where irregular distribution of heat created different gradations of color and vitrification of brick surfaces. Both of these factors were recognized by John Nicholas Brown II in a letter written to Norman Isham in 1936 following the Newport Chamber of Commerce’s request to remove paint from the building’s exterior:

I have written them that we decided at the time of the restoration not to remove the paint (1) because the brick was porous and seemed to need a coating of paint for water-proofing and (2) in order to hide the difference in colour between the old and new.

Brown, in a subsequent letter to the Newport Chamber of Commerce, noted that “Mr. Isham also felt that paint had been used originally on the building.” In a note contained in The Architectural Heritage of Newport, Rhode Island, Vincent Scully and Antoinette Downing speculate:

…..There is good reason to believe that Harrison finished the entire building with some kind of smooth coating (which would explain the use of different kinds of brick) to imitate the stone or stucco preferred by the English proponents of the academic style.

Historic views and photographs of the building show more uniform colors and surfaces that accentuate the building’s classical details. In a painting of 1818 (“The Parade” – Newport Historical Society Number 94.4.1) the body of the building is shown as a reddish/brown with white trimmings. While this view may be taken to show the building was originally exposed brick, it is equally likely that it shows an exterior washed with iron oxide or coated with either limewash or paint to provide a unified color, as such treatments were common methods of protecting masonry. Subsequent nineteenth-century photographs show a light-colored body with light trim (Newport Historical Society image #P380 – ca. 1875), and a light-colored body with dark trim (Newport Historical Society image #P15). As the various photographic processes used in the nineteenth century can affect the apparent level of contrast between colors, these photographs only offer a suggestion of the building’s color values. At the time of the 1928-30 restoration, it was noted that “the yellow paint applied in the nineteenth century was removed from the bricks.”

Analysis of remaining paint/coating fragments would provide the best opportunity to identify early colors

Roof

Original roof coverings have not been documented; however, when inspected by Norman Isham in 1916, the building had a severely weathered roof of wooden shingles that was replaced with slate. No reason was provided for this change of material; however, it seems likely that the fire-resistant quality of slate was one of the reasons for its selection.

Interior

The interior has not been documented as part of this examination.

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian

Sources

Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. Old-Time New England 6, No. 2 (January 1916), Serial 13: 2-11 & 20-21.

Lozupone, Alyssa. “Norman Morrison Isham: Newport Restoration Foreshadows Modern Preservation.” Senior Thesis,Salve Regina University, December, 2010: 46-60.

Downing, A. & Scully, V. The Architectural Heritage of Newport, Rhode Island. New York: C. N. Potter, 1967.

Newport Historical Society. Museum of Newport History at the Brick Market. https://issuu.com/newporthistorical/docs/brick_market_mock_up_9.16

Wikipedia: Peter Harrison. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Harrison_(architect)