Notable Elements

- Exceptional survival of construction documents including detailed specifications for all materials, plans & elevations, and financial accounts [History]

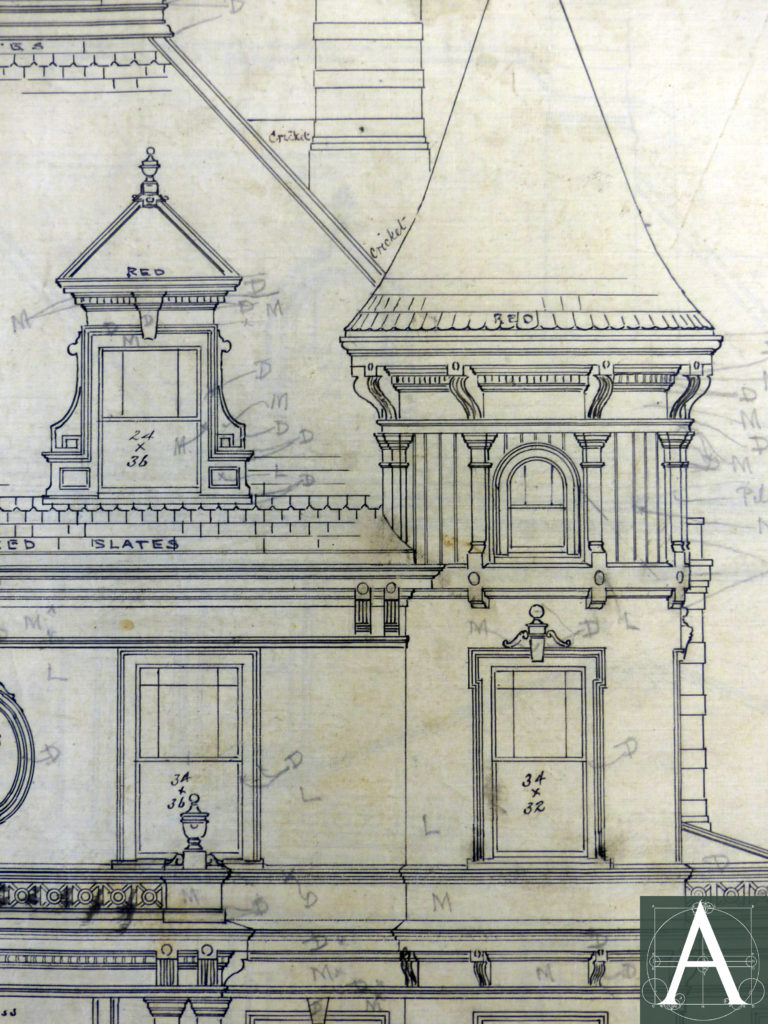

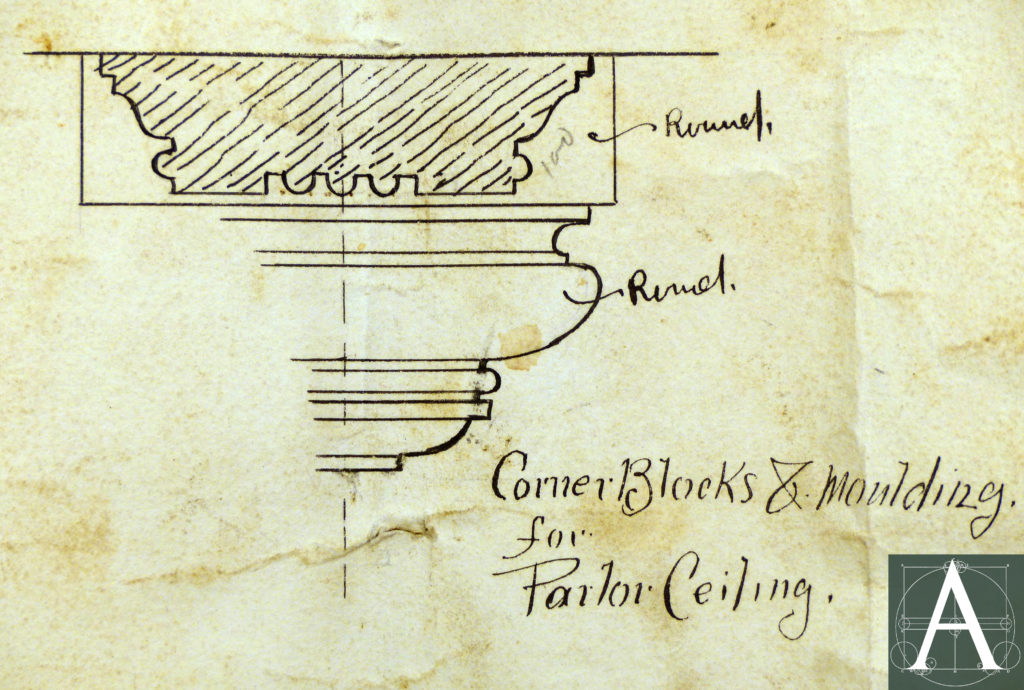

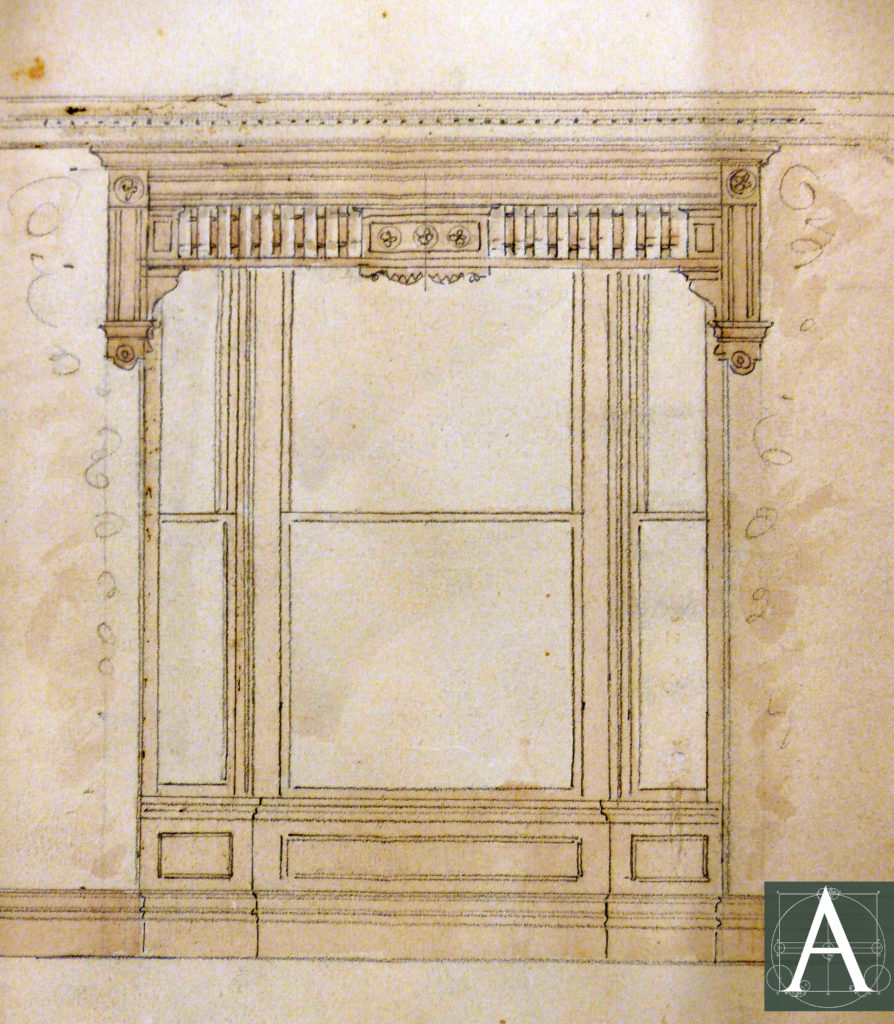

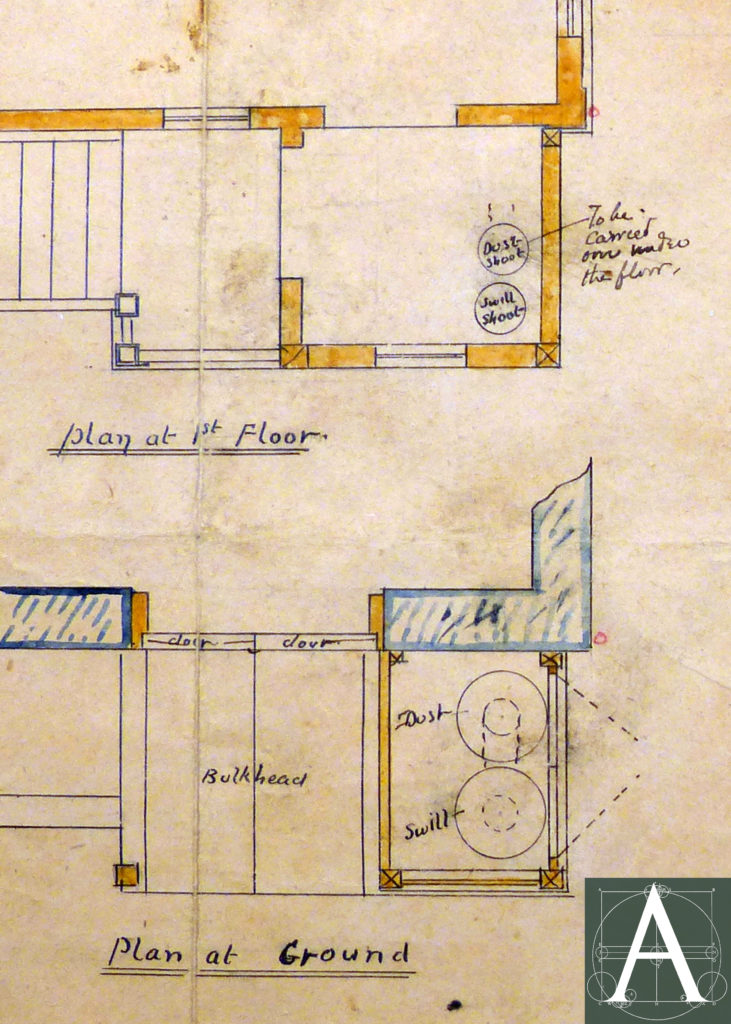

- Architectural plans, elevations and details from 1884-85 & 1905-12 [History, Exterior & Interior]

- Selective use of varied mortars for different applications [Foundation & Interior – Chimney]

- Details of methods and materials used to finish in interior woodwork [Interior]

- Details of plumbing, heating and domestic services [Interior]

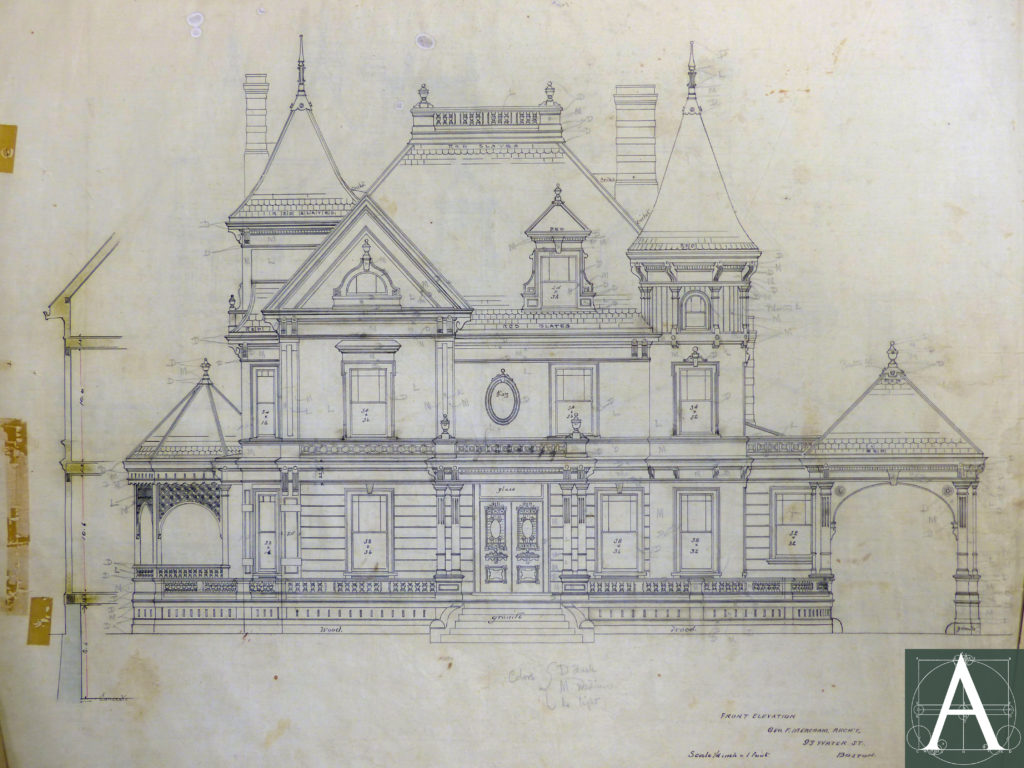

Façade of the Hartley Lord House from George Meacham’s 1884 plans for the house [courtesy of the Brick Store Museum]

History

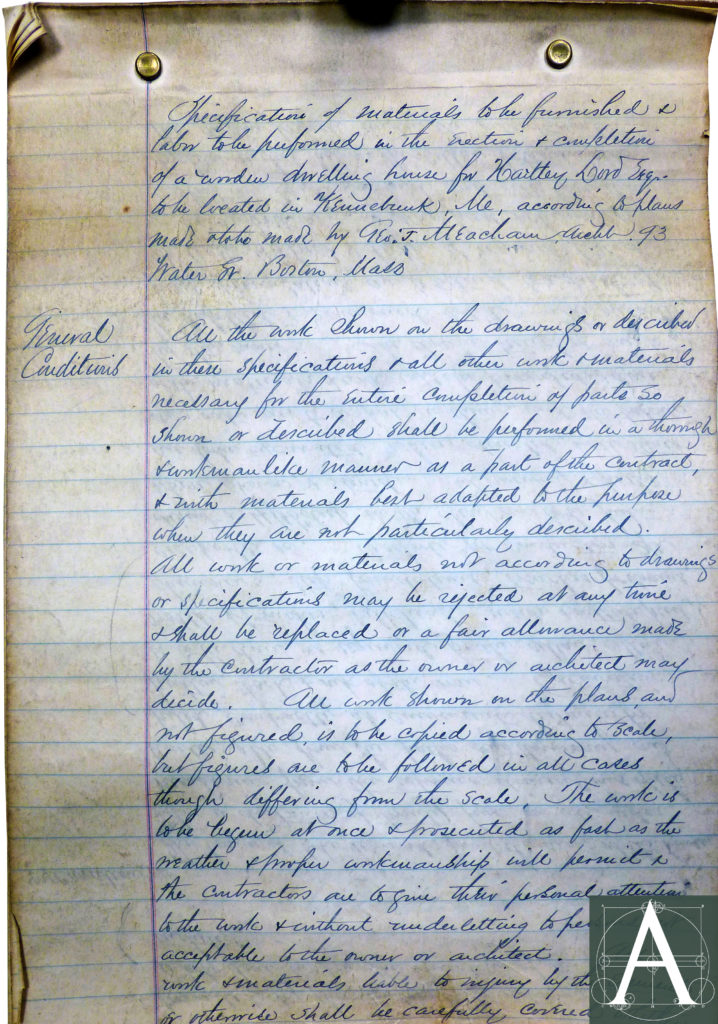

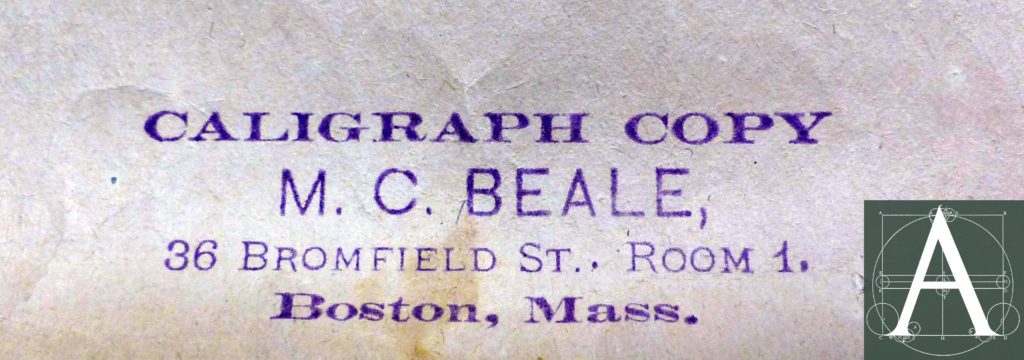

The Hartley Lord House is notable both for its well-preserved elaborate design and for the survival of its original construction documents, now held in a publicly accessible collection at the Brick Store Museum. These documents include plans and specifications that describe details such as the species of wood to be used for the house’s frame and finishes, brand-name hardware for doors and windows, surface finishes for woodwork, the various composition of mortars for masonry, plumbing lines, and many other elements. Even the written specification itself provides interesting technological record of its time. The full specification of thirty-five pages was initially handwritten by a clerk and annotated with sketches from the architect. Excerpts from the specifications were prepared for submission to different contractors, documents that were customarily handwritten by clerks prior to the fourth quarter of the nineteenth century, or that were occasionally printed by the late 1860s (Roger Reed. “Specification of Masons’ Work…” pp.i-viii). Taking advantage of the newly introduced technology of typewriters, the architect had these excerpts typed by M. C. Beale on Bromfield Street in Boston. Typed sections were labeled “Caligraph Copies” indicating that they were probably typed on a Caligraph 2 typewriter that was introduced in 1882; it offered both lower and upper case letters, unlike the Caligraph 1. The Brick Store Museum’s collection also includes Hartley Lord’s account books and correspondence that may contain additional information about the house’s construction.

The specification includes so many details of construction that it cannot be summarized effectively and is provided in a complete transcription (pdf copy) attached to this listing.

M.C. Beale’s label on typescript copies of excerpts from the full 1884 building specification [courtesy of the Brick Store Museum]

The façade elevation of the Carriage House as re-designed by George Meacham [courtesy of the Brick Store Museum]

George Meacham (1831-1917) was a native of Watertown, Massachusetts, who attended Harvard College as an undergraduate before moving to New Jersey to work as a civil engineer at the Jersey City Waterworks for two years. Meacham studied architecture in the office of an as-yet unidentified architect from 1855-57, after which he formed a partnership with Shepherd S. Woodcock. Meacham’s most well-known work is the landscape design of the Boston Public Garden (1859), although the overwhelming majority of his subsequent commissions were buildings. He remained in partnership with Woodcock until 1865, after which he practiced independently. The building documents for the Lord House provide a rare and detailed view of architectural planning, construction details, and materials specifications in the late Victorian era. The large scale of the house and the formal life to be lived in it are reflected in the hierarchy of materials and details selected by the architect. These ranged from plumbing drains and their methods of attachment to the species of wood employed in the building’s frame, detailed drawings of window sconces and cornices, the composition of masonry mortars, and even details of garbage disposal for the household.

The firm of Hutchins & French prepared plans for enlargement of the house’s rear wing, which were partially implemented but which did not change the main block of the house. One of the firm’s principals was Franklin H. Hutchins (1871-1934); details of his partner French are not currently available. The firm was known more for its bank buildings and commercial work than for its domestic designs.

Date

1884-85; 1905-12

Builder/Architect

George Meacham, architect, Boston, Massachusetts (1884-85)

Hutchins & French, architects, Boston, Massachusetts (1905-12)

Building Type

Queen Anne Style single-family house

Foundation

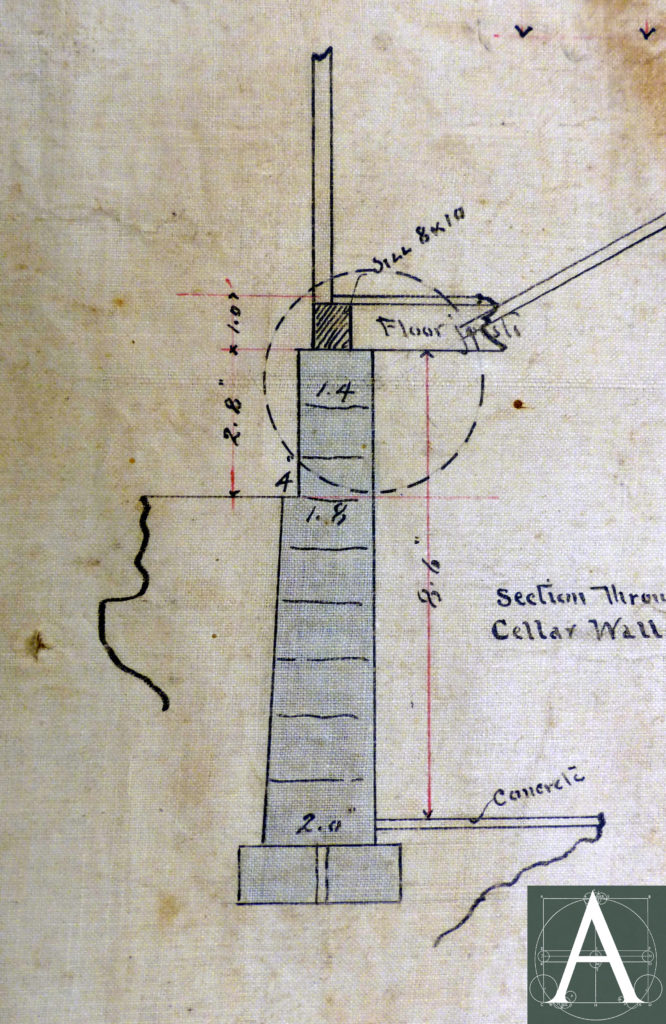

Pages 2-6 of the specifications: Foundation, drains, cesspools, drainage pipes and walkways were all laid out by the architect and built as part of the foundation construction. Specifications called for the removal of all topsoil for a distance of twenty-five feet from the perimeter of the house and for excavation down to “hard bottom” at least 4’-6” below grade or as deep as needed to provide a solid footing and clear interior height of 8’-6” once the cellar was finished. Foundation walls were set on squared stone underpinning blocks that extended beneath the cellar floor, above which the wall was constructed of ledgestone tapering from 2’-0” to 1’-8” thick at grade. Above grade it rose at a uniform thickness of 1’-4” to the base of a wooden sill. The bottom courses were carefully laid with 2” spacing between stones to provide a pitched drain toward drainage pipes at the building’s corners. Above the footings, the cellar walls were laid with a hybrid cement-lime mortar made of “1 cask of fresh Newark cement to 2 casks of best Rockland lime, & proper allowance of coarse sharp sand.” The Newark cement was a natural cement from the Newark Lime & Cement Manufacturing Company of Roundout, New York, which was one of many natural cement producers that established themselves in the vicinity of Rosendale, New York, following the discovery of limestone that could produce hydraulic lime and natural cement after 1825. Initially used on a large scale for construction of the Erie Canal and engineering works because of its ability to set in the presence of water, natural cement became a widespread material in high-quality masonry construction of the late nineteenth century. The Rockland lime came from Rockland, Maine, where high-calcium lime began to be produced for plasters and mortars around 1733 and rose to large-scale production by the early nineteenth century. This hybrid lime-cement mortar is one of several different mortar formulations specified for different applications in the Lord House.

At all elevations, the foundation of the main house was concealed by verandahs. Entry steps and supports for the “carriage porch” were to be made of hammered granite “free of rust & other imperfections” while the exposed portions of cellar wall beneath the kitchen wing were to be made of split-faced granite ashlar bedded in cement mortar without lime.

The cellar floor was also specified to make use of Newark cement, but without the addition of lime in order to produce a harder surface. Upon completion, the cellar walls and piers were to be covered with two coats of limewash, a traditional material used to brighten and sanitize utilitarian spaces. It is probable that this limewash was made using Rockland lime putty thinned to a liquid; following application, it would carbonate and return to calcium carbonate providing a protective surface that brightened cellar rooms. This material is the same that was used as an exterior coating in masonry buildings before the Industrial Era (see Historic Masonry Coatings Glossary).

Drawn section of the foundation showing the wide footings, inward battered foundation wall below grade and the straight-walled foundation above grade [courtesy of the Brick Store Museum]

Frame

Designed by the architect and shown in framing plans, the house’s wooden frame was to be ordered by the owner separately from the Kennebec Framing Company, which was to deliver it “fitted and adjusted.” Wood for the frame was specified as “straight-grained, square edged spruce…framed according to the plans & directions…raised, pinned, spiked and bolted together.” Instructions for the frame indicate that it was a braced frame (modified timber frame) with mortise-and-tenon joinery as well as more modern bolting and other fastenings. (pp. 13-14)

Back Plaster: Studs were spaced 12” on center and had wooden strips (⅞” x 1¼”) nailed on each side to receive “horizontal lathing for back plastering.” Largely forgotten by builders and often unrecognized by historians, back plastering was used extensively in the nineteenth century in good-quality construction to reduce drafts and to provide a measure of insulation.

The contractor was also instructed to “put two courses of light hard bricks laid in cement on all sills and between the studs of all partitions and fill up all the holes for rat proofing.” (p. 8)

Exterior

Siding & Trim: Because of the number of different details applied to the exterior, references to it occur in several locations in the specifications. The basic wall finishes were to be made of:

“the best thoroughly seasoned soft pine & well wrought…..The entire walls are to be covered with ‘Beaver’ brand, or some other approved standard tarred paper…The walls of the first story are to be covered with tongued & rebated sheathing as shown, and the second story with narrow, tongued, plain sheathing of uniform & parallel widths not exceeding 4” before working, & the whole evenly smoothed & primed when put on. (p. 19)

The exterior was elaborately decorated with ornamental railings, cornices, brackets and other woodwork that were shown in plans and details but not described in writing. Exterior surfaces were to have “three heavy coats of three colors as may be selection by the owner, made of the best materials, the colors to be ground in oil…” Either the architect or owner marked individual elements on each elevation in pencil with “D” for dark, “M” for medium, and “L” for light color. (p. 32)

Detail of the façade elevation showing the architect’s handwritten annotation for the relative color values of exterior paint [courtesy of the Brick Store Museum]

Stained and colored glass: “…colors of light shades of cathedral glass” were to be provided by the contractor and installed on “outside doors, sashes & headlights…also the outside side & vestibule doors.” Stained leaded glass, presumably figural or geometrically patterned glass, was to be provided by the owner for the main stair hall, dining room window transoms and a “headlight over the dining room sideboard.” The contractor was responsible for setting the stained glass in frames with iron backer rods, and the painter was responsible for coating the exterior of the leading “with best liquid gold bronze” (pp. 32-33), a finish that is rare in its survival on exterior surfaces in houses of this period.

Blinds & Screens: With the exceptions of small cellar, dormer, and windows in the upper part of the tower, all windows were to be fitted with “1⅜” outside blinds, with heavy rails, pinned, made in four folds where required to swing, with rolling slats [operable louvers] in the lower panels, & hung with stout braced hinges” (p. 18). All windows excepting the unfinished parts of the attic were fitted with “fine painted wire mosquito screens for lower halves of windows with ⅞” stout beaded frames of black walnut and spring slides or brass bolts as the owner may decide for holding them in position and guides.” (p. 19)

Roof

The slopes of the house’s complex roof appear to retain most of their original slates and details. Specifications call for “the best quality of Monson slate, the principal size to be 16” x 10”, not less than 52 to a foot, and with unfading red slates for under the eaves and the first courses above the gutters.” Slates were laid on “tarred paper” and nailed with galvanized iron nails. Valleys between slate sections of the roof were lined with 10 oz. zinc nailed in place with galvanized iron nails. In addition, 16 oz. copper was specified at crickets behind chimneys. “M.F. roofing tin” was specified for the heads and stools of some of the windows in addition to flat roofs, gutters, and downspouts, all of which were to be locked, cleated and soldered. (pp. 10-11)

Interior

Interior elements of the house, both functional and decorative, are exhaustively defined in the specifications and plans; the following are merely a sampling of details for which information usually does not survive for houses of this period. Hartley Lord’s correspondence has not been thoroughly researched with regard to the house’s construction and may contain correspondence that could explain architectural and aesthetic choices, as well as the interaction among the architect, owner, and builder.

Woodwork & Finishes: A wide variety of woods was used on the interior, some selected for their functional value, others for their decorative effect. Blind-nailed hardwood floors consisting of oak with a patterned border of oak and cherry in the dining room reflect a then-modern taste for exposed wood floors with scatter rugs, rather than strips of carpeting stitched together to form wall-to-wall floor coverings as was common in the first three quarters of the nineteenth century when floors were typically unfinished pine, never intended to be exposed to view. The architect added a small sketch of the floor pattern to the margin of the specification. (p. 16) “All other floors [were] to be first quality spruce…..All these floors are to be jointed, strained tight, smoothed, & the hardwood traversed & sandpapered for varnishing.” (pp. 16-17) Exceptions to this general specification were “the kitchen, wash room, Pantry & back stair hall,” which were to be of birch, and the china closet, which was to have an oak floor.

Architect’s detail of the proposed cornice in the parlor and wooden trim at door casings [courtesy of the Brick Store Museum]

Interior hardwood finishes were “filled and oiled as may be directed, and then covered with a coat of white shellac and two coats of Berry Bros. light hard oil finish, full strength, and when hard buffed down with powdered pumice.” “The woodwork of chambers is intended to be oiled and finished like the hardwood, but the painter will, perhaps, be required to shellac & paint in particolors some of the rooms. Plaster walls in most parts of the house were to be finished with “four heavy coats of pure lead & linseed oil tinted as directed. No sizing to be used. Finish with stippling.” (pp. 32-34)

Architect’s colored sketch of one of several options for decorative woodwork at the parlor bay window. [courtesy of the Brick Store Museum]

One of several drawn details of the kitchen entry vestibule showing the placement of dust and swill containers with clean outs at grade elevation [courtesy of the Brick Store Museum]

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian

Sources

Brick Store Museum. Inventory of the Robert Beardsley Collection (Collection #93). Building plans and specifications for the Hartley Lord House. http://www.brickstoremuseum.org/collections/

http://www.brickstoremuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Coll49_HartleyLord.pdf http://www.brickstoremuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Coll93_Beardsley.pdf

Lord, Charles Edward. The Ancestors and Descendants of Lieutenant Tobias Lord. Privately Printed, 1913. pp. 230-231. Digital copy: https://archive.org/stream/ancestorsdescend00lord#page/n13/mode/2up

Reed, Roger. Introduction to: Specification of Masons’ Work and Specifications for Carpenters’ Work. Facsimile edition of 1869 printing. Illinois: Small Homes Council-Building Research Council of the University of Illinois, 1989. pp. i-viii.

Shettleworth, Earle, editor. Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Maine. Maine Historic Preservation Commission. George Meacham biography: http://www.maine.gov/mhpc/architects_bio.html

Shettleworth, Earle. Society of Architectural Historians. http://www.sah.org/docs/misc-resources/brief-biographies-of-american-architects-who-died-between-1897-and-1947.pdf?sfvrsn=2 (Hutchins listed)

The Virtual Typewriter Museum. Caligraph1 & Caligraph 2. https://www.typewritermuseum.org/collection/index.php3?machine=caligr&cat=ku

Wikipedia: George Meacham. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Meacham