Jonathan & Simon Hosmer House, 300 Main Street, Acton, MA – façade (south elevation) [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Notable Elements

- 1760 exterior plaster & original imitation brick finish [Exterior]

- Central chimney laid in clay with arched heads at fireboxes [Interior]

- Social patterns of multi-generational occupancy [History]

- Pre-1800 clapboards [Exterior]

- 1796 Beverly Jog at northwest corner [Exterior]

- Fieldstone foundation with gallets remaining in place [Foundation]

History

The Hosmer House was built in two stages for two generations of the Hosmer family, namely, Jonathan Hosmer Jr. (1735-1822) and his son, Simon Hosmer (1774-1840). Extension of an existing central chimney house to create a separate, but internally connected, house was a frequent pattern in New England from the seventeenth century into the nineteenth century and can be seen in houses such as the Cooper-Frost-Austin House (Cambridge, Massachusetts) and the William Howard House (Ipswich, Massachusetts). Equally common was the subsequent conveyance of the house by Jonathan Hosmer to his son in 1797 upon the condition that the younger Hosmer provide for his parents’ care and upkeep in the house for the remainder of their lives.

In addition to being a farmer, Jonathan Hosmer Jr. was a bricklayer and mason. It seems probable that he built substantial portions of both sections of the house, including the cellar walls, chimneys and fireplaces, as well as the original plastered west gable. Since lime mortars and plasters are substantially the same material, it is probable that Hosmer also plastered the house’s interior where plaster walls are set on thick riven laths that match those of the west gable.

Date

1760; enlarged 1796

Builder/Architect

Jonathan Hosmer Jr., mason (attributed)

Building Type

The original 1760 portion of the house is a two-storey, center-chimney house with a timber frame composed of two structural bays in length at its southern half and three bays in an integral lean-to at its northern half. Unlike the most common examples of form of center-chimney house, the Hosmer House does not have a separate chimney bay, nor does it have an entry lobby or staircase in front of the central chimney; instead, the main entry opens directly into a parlor without a staircase. The only staircase in the original portion of the house rises in a narrow well accessible only from a position immediately east of the kitchen hearth in the lean-to. At the attic, the roof is framed by principal rafters into three bays to provide a central bay in which the rafters flank the chimney.

The house was enlarged in a manner characteristic of many New England houses occupied by two generations of the same family, by the construction of a half-house containing two rooms per storey at the west end of the original house. The addition is served by a chimney at its west gable. The addition’s entry opens directly into the front parlor and its staircase is concealed in a narrow well at the southeast corner of the kitchen, a pattern that resembles the plan of the 1760 house.

Foundation

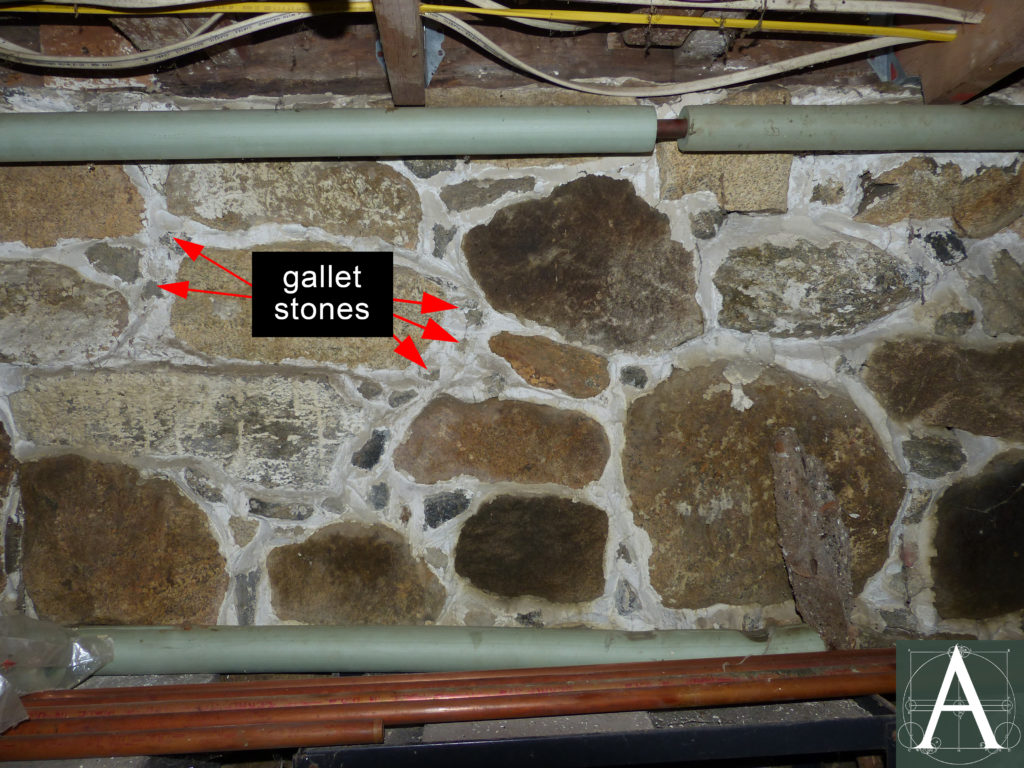

The original house contained a partial cellar beneath its east end. When the addition was constructed in 1796, this cellar was extended westward by a narrow passage on the north side of the cellar to a partial cellar beneath the addition. Typical of many seventeenth- and eighteenth-century houses, the bases of both chimneys were built on grade and stabilized by stone foundation walls enclosing unexcavated earth. Foundation walls are made of large fieldstones set with point-to-point bearing; irregular joints were filled out with gallet stones to reduce the amount of mortar as well as the shrinkage of lime mortar needed to close the joints. A high proportion of lime mortars and gallet stones remain undisturbed in these cellars and are reminiscent of foundation walls at the Spencer-Peirce-Little House (Newbury, Massachusetts).

Cellar – base of central chimney showing stone walls that retain unexcavated earth [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Cellar – typical stone wall showing large fieldstones laid with point-to-point contact and smaller gallet stones to fill irregular, wide joints [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Frame

The original house is framed as three structural bays with an integral lean-to. Some timbers in the attic and west gable appear to be oak. Full analysis of the frame’s timbers is not available. The 1796 addition appears to have used the same structural system, extending the original frame westward by two structural bays.

East and north elevations of house showing the integral lean-to roof [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Exterior

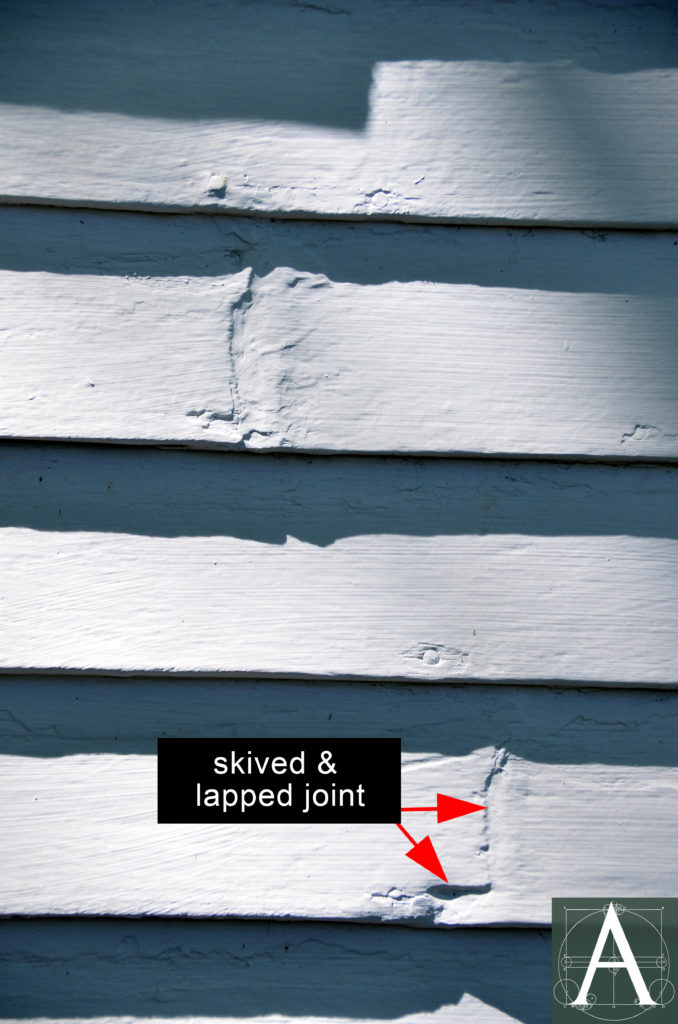

The present appearance of the house post-dates 1796. The matching front doorways with their pilasters and entablatures are believed to have been added at the time of the west addition. Existing clapboards with their skived, lapped joints are also likely to date from this period or the first quarter of the nineteenth century. At the east gable sections of early clapboard remain with their pattern of staggered butts vertically aligned at every other course of clapboard. Also added in 1796 is a “Beverly Jog” at the northwest corner of the house. Seen throughout much of New England, but more frequently in Essex County north of Boston, Beverly Jogs are extensions enclosed by only one slope of a main roof, leaving a full-height wall on one face of the addition which frequently serves as a rear entry to kitchens or rooms in the rear range of houses.

West elevation of 1796 addition showing the Beverly Jog at the northwest corner providing access to the kitchen [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

South elevation – detail of skived and lapped clapboards (ca. 1796) [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Two other prominent examples of exterior plaster on timber-frame buildings survive in the Hooper-Lee-Nichols House (1685, 1733 & 1758, Cambridge, Massachusetts) and the Pellet-Barrett House (1728 – Concord, Massachusetts); however, both of these were originally scored to imitate stone ashlar. Both have been exposed to the weather for more than two centuries and have been painted many times, concealing evidence of their original coatings and colors.

View of original (1760) west gable with exterior plaster remaining on riven lath [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

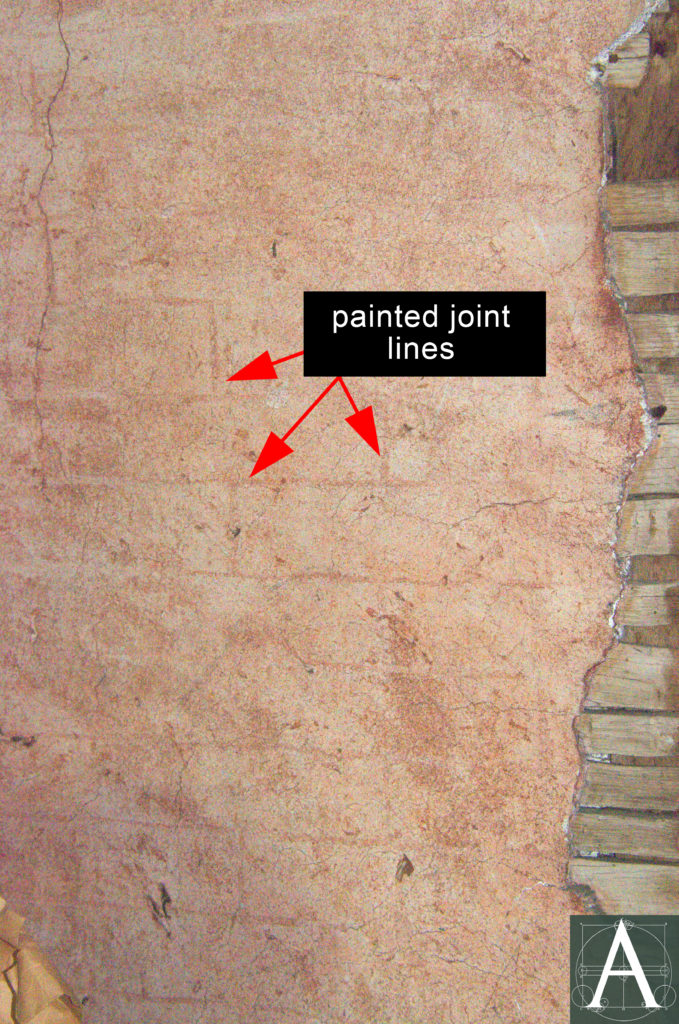

Close-up view of protected area of exterior plaster showing brick pattern painted onto smooth-finished surface [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Larger section of exterior plaster exposed to weather; former false mortar joints shown as slightly darkened lines forming a brick pattern [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

View of weathered exterior plaster and underlying lath with skived ends to form lap joints with adjacent lath [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Riven lath at the south end of the former west gable after removal of exterior plaster [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Interior plaster applied to back sides of riven lath at the south end of the former west gable [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Roof

The house’s integral lean-to roof is covered with modern wooden shingles. Original cladding materials have not survived and are conjectured to have been wood shingles.

Interior

Built as a central-chimney house, the layout of rooms in the Hosmer House is unusual for two details. Unlike the characteristic center-chimney, center-entry New England house, it does not have an entry hall or staircase rising from a central location in front of the chimney to the second floor. Instead, the main entry opens directly into a room, and the staircase rises in a narrow well entered from the kitchen at the rear of the house. This arrangement was duplicated in the west addition to the house.

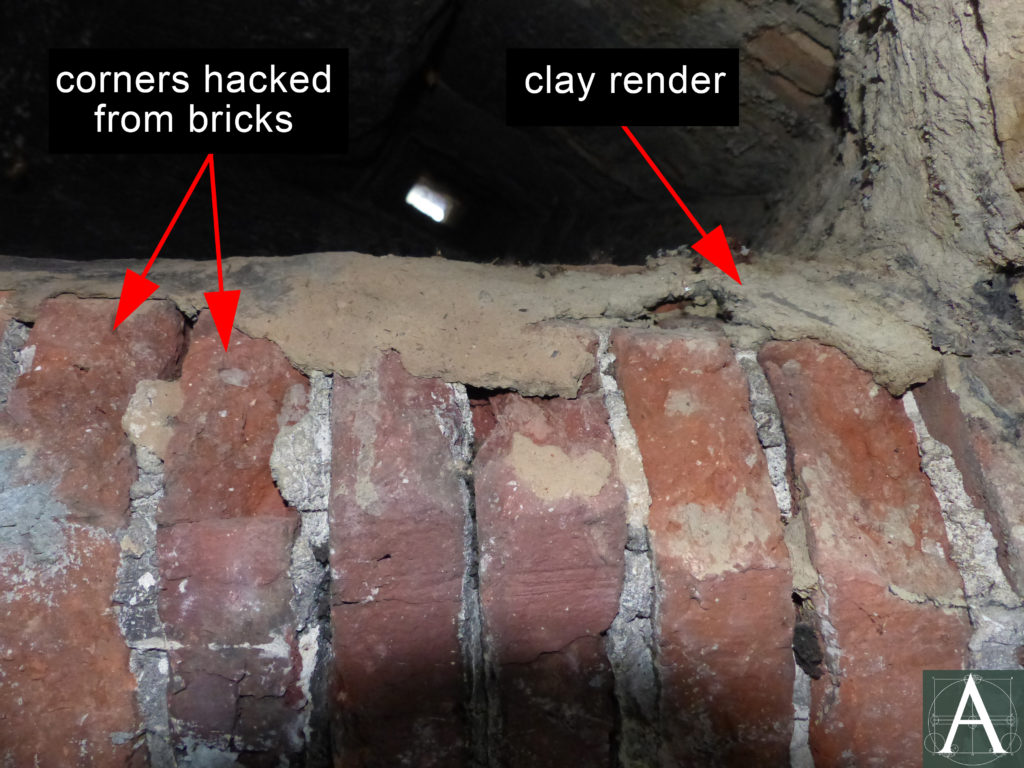

A second unusual feature of the house is the arrangement of its central chimney with fireplaces set at irregular angles facing into the south rooms. Characteristic of many New England houses of the period, the central chimney rests on unexcavated grade that has been surrounded and stabilized by stone walls at the cellar. From the base of the stack to the base of the attic floor, the chimney’s bricks are laid in clay/earth mortar. It is probable that the chimney originally was laid in clay/earth mortar through the attic, but evidence for this conjecture was lost in the 1970s when the chimney was rebuilt from the attic floor to the ridge.

View of the fireplace in the southeast chamber at the second storey [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

View of the underside of the fireplace arch at the second-storey southeast chamber showing roughly hacked bricks and clay mortar plastered on broken bricks to provide a smoothly curved surface [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

View of the clay-plastered flue at the second-storey southeast chamber’s firebox [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

- Southeast Parlor (first storey): arched opening 39½” wide x 23½” high at the jambs x 28½” at the height of the arch; angled side walls 18½”; back wall 20½”

- Southwest Sitting Room (first storey): arched opening 53½” wide x 27½” high at the jambs x 34” at the height of the arch; angled side walls 23½”; back wall 27”

- Southeast Chamber (second storey): arched opening 39” wide x 23” high at the jambs x 27½” at the height of the arch; angled side walls 18½”; back wall 20½”

- Southwest Chamber (second storey): arched opening 42½” wide x 23” high at the jambs x 28¼” at the height of the arch; angled side walls 19½”; back wall 20”

Fireplace in the southeast parlor (best room) at the first storey [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Typical red-painted border, one header wide (4”) at the face of the splayed sidewalls of the fireplace in the southeast parlor at the first storey [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Curved bolection moulding (ca. 1760?) at the head of the fireplace in the southeast parlor at the first storey [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Large bake oven at the kitchen fireplace showing the domed construction, brick floor and clay mortar with later patches [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Storage vault beneath the large bake oven showing the roughly plastered sidewalls, wooden sleepers at the vault’s ceiling and bricks laid in clay mortar above [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society

Domed structure of the small bake oven showing bricks bedded in clay mortar [courtesy of the Acton Historical Society]

Contributors

Anne Forbes, historical research from National Register Nomination

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian, field survey May 20, 2017

Sources

Massachusetts Historical Commission: National Register of Historic Places Nomination – http://mhc-macris.net/Details.aspx?MhcId=ACT.168

Wikipedia: Jonathan and Simon Hosmer House https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jonathan_and_Simon_Hosmer_House