Spencer-Peirce-Little House – façade & east elevation showing the original stone house (right) and 1796 wood wing (left) [image with permission from Historic New England]

Notable Elements

- Original exterior limewash and color [Exterior]

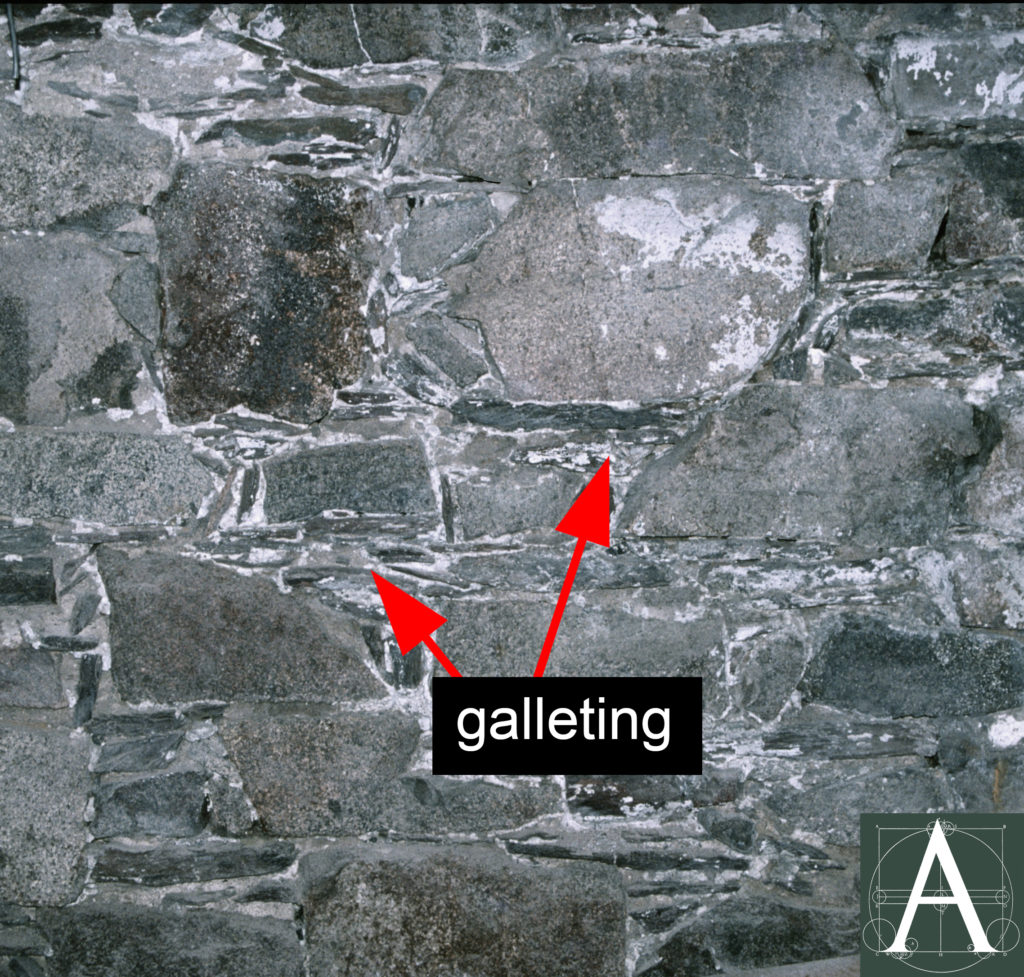

- Galleting at stone walls – traditional masonry construction practice [Foundation]

- Use of lime mortar as a caulk at pre-1796 window surrounds [Exterior]

- Clay mortar at base of central chimney [Foundation]

- Lime plaster on riven lath at underside of roof [Interior]

Spencer-Peirce-Little House – façade & east elevation ca. 1940 showing extensive remains of limewash (from Howells’ Architectural Heritage of the Merrimack)

History

The Spencer-Peirce-Little House is set back off the High Road in the center of a large farm which retains the majority of its original 400 acres granted to John Spencer in the early settlement of Newbury in 1635. In 1648, the property was sold to Daniel Peirce, Senior, whose son, Colonel Daniel Peirce, inherited the property upon his father’s death. The younger Peirce was a prominent merchant in that portion of Newbury that came to be known as “Waterside” and was later incorporated as Newburyport, a mercantile town with political interests different from the rest of Newbury which was agrarian. Peirce initially created an entail on the property, indicating that he intended to create a country seat that would descend in his line, in the manner by which English estates were passed to the eldest son or nearest male heir, thereby making them inalienable within one family. The entail was eventually broken and the property sold out of the Peirce family in 1778 to Nathaniel Tracy, a Newburyport merchant and privateer during the Revolutionary War, who made some alterations to the building’s interior and central chimney. Upon Tracy’s death in 1796, the farm was sold to Offin Boardman, a Newburyport merchant who had also been a privateer during the Revolutionary War. Boardman constructed the wood-frame west wing of the house in addition to an attached farmer’s house at the rear of the original stone house. These additions brought the building to its present form.

The Spencer-Peirce-Little House is rare example in New England of an attempt to create manor house architecture and accompanying social aspirations. Built around 1690, the house’s stone construction is unique in Eastern Massachusetts. During this period, sources of building lime in the region were few, while plentiful lumber encouraged settlers built nearly exclusively in the timber-frame tradition they brought with them from England, especially from East Anglia. As initially constructed, the house had a cruciform plan with a mixture of stone walls trimmed with brick, all of which was covered with multiple layers of white limewash. When the west wing was constructed for Offin Boardman in 1796, it was placed directly against the house’s original west wall, concealing and protecting numerous masonry finishes that have not survived on other elevations of the building or on more than a handful of buildings of the period. [Exterior]

Conservative maintenance of the house over subsequent generations retained extensive evidence of original masonry construction of the period in which rubble construction of the period was laid up with gallet stones to fill the wide joints created by fieldstone. [Foundation]

In addition to its masonry features, the house retains many regionally significant architectural elements from Georgian modifications made by Nathaniel Tracy around 1778 and in the Federal style wood-frame wing added by Offin Boardman in 1796.

Date

1690; 1778; 1796

Builder/Architect

unknown

Building Type

Unique plan, not classifiable within New England vernacular building types

Foundation

To make economical use of lime mortar and to reduce the effects of its tendency to shrink in curing, rubble-stone construction was traditionally laid with point-to-point contact between large stones and joints were packed out with small stones (gallets) to fill the wide and irregular joints left by the shapes of undressed stones. Gallets have been removed from the majority of buildings as a result of raking out weathered mortar joints for re-pointing. Modern cement-based mortars tend not to shrink as much as lime mortar during its curing with the result that the function of gallets has largely been forgotten and their removal passes unnoticed. Gallets also served to create a relatively smooth surface to receive limewash or plaster. The masonry walls of the cellar retain substantial areas of original masonry that is protected from weather and that has not been altered by subsequent re-pointing.

West wall of the 1690 cellar showing galleting used to pack out joints between irregularly shaped field stones [image with permission from Historic New England]

Clay mortar joints with fragments of protective white limewash clinging to brick and stone faces at the east face of the central chimney’s base [image with permission from Historic New England]

Close-up view of clay mortar at base of 1690 central chimney [image with permission from Historic New England]

Frame

Exterior

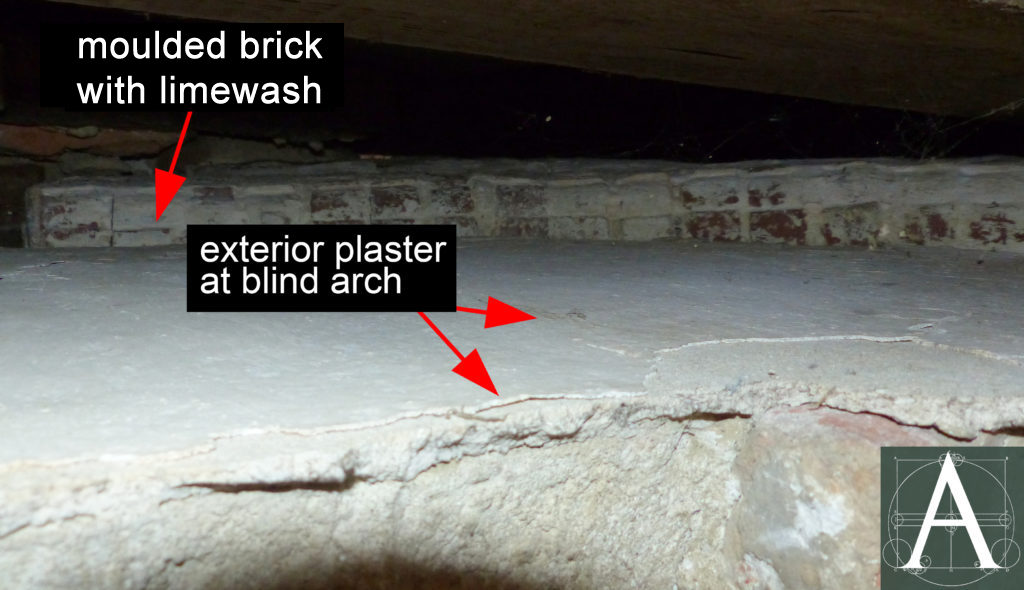

One of the most notable elements of the house’s masonry is the survival of substantial areas of its pre-1796 exterior limewash, especially on the west gable of the original house which was enclosed by the Boardman addition of 1796. The depth of limewash layers on this gable, and traditional English building practices suggest that it was an original treatment, or, at least, that it had already been in long usage prior to 1796.

Full coating of limewash at the original west gable, now protected by the 1796 wood wing [image with permission from Historic New England]

Detail of limewash and mortar bevel at former underside of the original rake board (removed from position of bare brick) at the west gable [image with permission from Historic New England]

Window head at the west gable showing mortar used to caulk the gap between masonry and the wooden window frame [image with permission from Historic New England]

Detail of original window head with plastered blind arch and moulded brick extrados covered with limewash – visible within the interior wall cavity at the first storey [image with permission from Historic New England]

Red paint on brick, over-painted from the window case, pre-1796 at the west gable [image with permission from Historic New England]

Red paint on interior window case at the south porch gable; paint matches the color found on the exterior of west gable windows, pre-1796 [image with permission from Historic New England]

Limewash remaining at intrados of the arch at south face of the two-storey entry porch [image with permission from Historic New England]

Limewash remaining at wall head protected from weather by eaves at the west face of the two-storey entry porch [image with permission from Historic New England]

East wall of original stone house after repair and re-establishment of limewash [image with permission from Historic New England]

Roof

The house is enclosed by a steeply pitched main roof that extends east-west with a full-height cross-gable at its north slope and a smaller gable at the head of the two-storey entry porch on the south slope. Roofs are supported by timber-frame structure with lime plaster on the underside of sheathing in selected areas of the seventeenth-century portions of the house that may have been formerly occupied as chambers. [Information needed.]

Lime plaster set on riven lath nailed to the underside of roof sheathing boards at the east gable [image with permission from Historic New England]

Interior

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer from personal inspection & unpublished reports

Sources

Howells, John Mead. Architectural Heritage of the Merrimack. (New York: Architectural Book Publishing Company, 1940) 164-167.

Historic New England: http://www.historicnewengland.org/historic-properties/homes/spencer-peirce-little-farm/spencer-peirce-little-farm-history

National Park Service: Spencer-Pierce-Little Farm Nomination to the National Register of Historic Places (1967). text:http://focus.nps.gov/GetAsset?assetID=1a70c680-b41b-4ee6-be49-66f62729fd7f; photographs: Spencer-Pierce-Little House National Register Photographs 1967