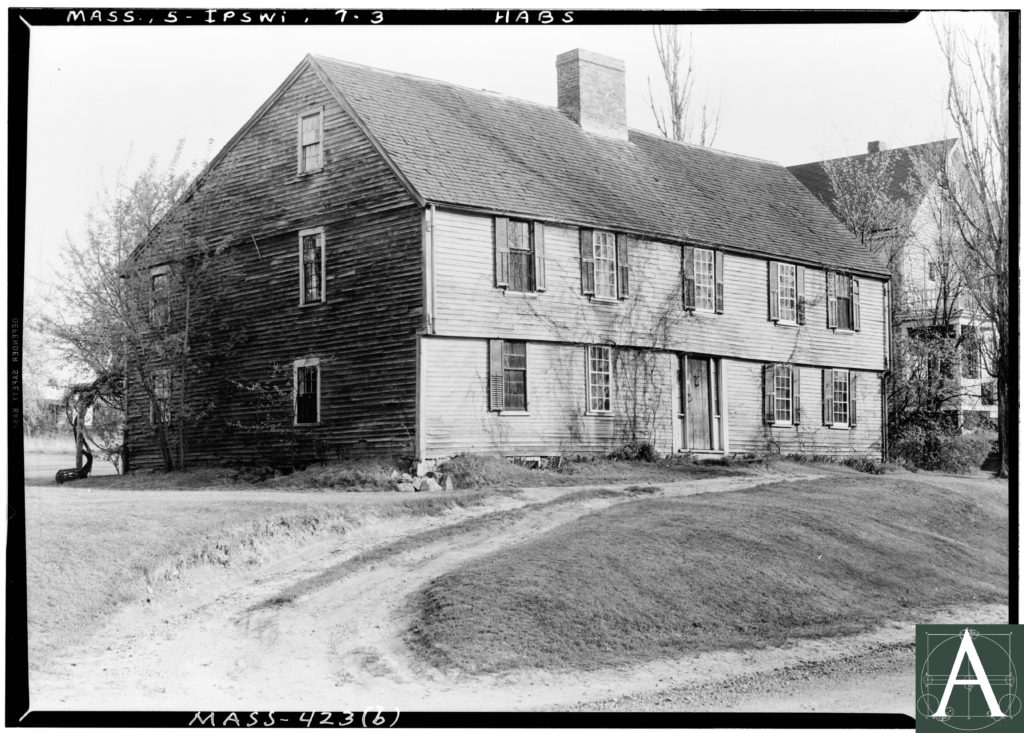

William Howard House, 41 Turkey Shore Road, Ipswich – facade and side elevation showing 18th century window placement & later cladding concealing hewn overhang (HABS, Arthur C. Haskell, photographer, 1933)

Notable Elements

- Early clay and straw plaster with possible original skim of lime [Interior]

- Partial restoration/conjectural reconstruction by William Sumner Appleton [Interior]

- social/architectural history – half house expanded to full center chimney house to accommodate multiple generations of the same family [History]

- clay plaster and brick nogging bedded in clay mortar [History & Interior]

- subdivision of original square rooms with board partitions to create “cabins” during the 18th century [Interior]

History

Called variously the Emerson-Howard and Howard-Emerson House and believed in the early twentieth century to have been built as 1648, the William Howard House appears to have been constructed in several stages, the earliest of which dates from 1680-1690.

The Howard House began as a characteristic timber-frame half house composed of two bays, namely a nearly square room bay (east) and a narrower chimney bay (west) containing the massive central chimney. First and second storeys each contained a single large room; the attic appears to have been unfinished. The façade’s second floor projected slightly over the first on a hewn overhang the base of which was trimmed with a moulding that was concealed by later alterations and then unknowingly removed by a contractor in the 1950s during exterior repairs. Wall cavities were filled with brick nogging bedded in clay mortar, and interior plaster consisted of clay and straw set on riven lath that was fastened to studs with rose-head nails.

In 1709, the house was expanded westward by a single room in a pattern characteristic of New England’s vernacular houses. Frequently, such additions were built to house a second generation of the family, and many such houses continued to be occupied by different generations of the same family well into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Cooper-Frost-Austin House in Cambridge, Massachusetts, follows the same pattern. A similar pattern can be seen at the Matthew Perkins House, Ipswich, Massachusetts, but with the difference that the house was built to its full size from its beginning. Documentation for the house’s enlargement comes from the will of William Howard, dated 1709, in which the addition is mentioned (“Architectural Evaluation of the William Howard House”. Abbott L. Cummings. See Sources below).

Further alterations were made prior to 1800 by the removal of the original central chimney and its replacement by a smaller chimney mass in same location. Exterior claddings were modified and interior partitions were added, subdividing large rooms in the original portion of the house into three “cabins” each. Window placement was modified, perhaps as early as 1709, but certainly by 1800, by the installation of double-hung wooden sash. Additions were also made to the rear of the house to provide service rooms.

Acquired in 1929, by the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (now Historic New England), the house underwent a partial restoration/reconstruction of seventeenth-century features in 1943 when the eastern half of the house was restored to its supposed original appearance, while the western half was left with its later, eighteenth century appearance. Work on the Howard House was supervised, William Sumner Appleton, founder of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, in consultation with Frank Chouteau Brown (1876–1947), a restoration architect. During this project, double-hung sashes were removed from the original portion of the house and replaced with tri-partite leaded casements conjecturally based upon evidence found in other buildings, as only fragmentary evidence remained in the framing of the Howard House. With its eastern windows re-built to contain tri-partite casements and its western windows retaining 9/6 double-hung sash, the house acquired an appearance that never existed during its history. This approach to restoration/reconstruction was taken on a number of seventeenth-century houses during the first half of the twentieth century, such as the Balch House in Beverly Massachusetts, where Rhode Island architect Norman Isham advised exposing and reconstructing seventeenth-century style details on the building’s oldest portion.

facade and side elevation showing mixed casement and sash windows after 1943 restoration (image courtesy of Historic New England)

East elevation showing partial reconstruction of 17th century style windows following 1943 restoration (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Date

1680-90; 1709; ca. 1800; 1943 (partial restoration/reconstruction)

Builder/Architect

Unknown

Building Type

Originally constructed as a timber-frame half house (1680-90); enlarged to a full center-chimney house in 1709

Foundation

Frame

Oak timber-frame subject to multiple periods of enlargement and alteration.

Exterior

Major elements of the house’s exterior, such as its hewn overhang (jetty) at the façade, its steeply pitched roof and slight asymmetry are characteristic of its period and type. Surfaces have been renewed in the twentieth century in a modern manner with long clapboards (probably cedar) with butt joints, faced nailed randomly with flat-head modern nails. Documentary photographs taken by Arthur Haskell for the Historic American Buildings Survey in the 1930s, appear to show the remnants of eighteenth-century or early nineteenth-century clapboards (probably white pine) between the western two windows at the second storey of the façade. In this location, there appears to be an area of evenly staggered, skived joints midway between the two windows, a detail that would have reconciled the four-foot lengths that were typical of many early clapboards. The photograph does not reveal the nailing pattern of these clapboards, but based upon customary practice, they were probably face-nailed with slightly protruding hand-wrought nails aligned in vertical rows on internal studs. It is likely that the entire exterior was clapboarded in this manner during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Although the current central chimney occupies the location of the original chimney, it is a smaller structure and its cap above the roofline is much smaller than would have been likely for the original chimney which was removed and replaced in ca. 1800.

Windows were restored to their documented eighteenth-century appearance in the early 1990s, by which time the conjecturally designed casements installed in 1943 had deteriorated due to the poor selection of construction materials and techniques [see Interior, below].

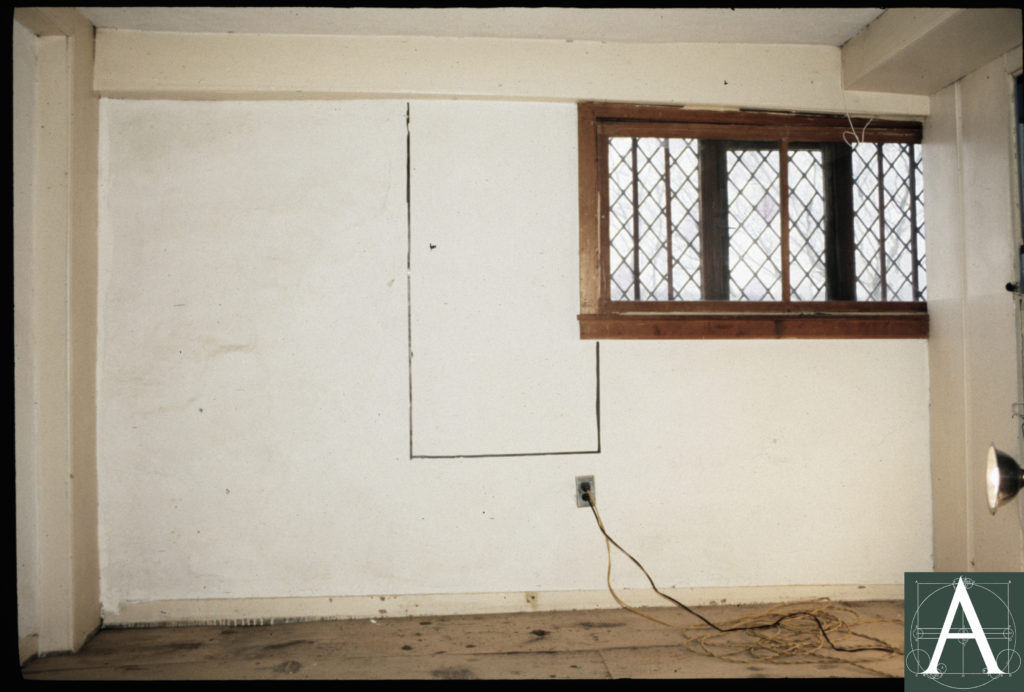

Interior east elevation showing typical tripartite casement window and the location of 18th century double-hung windows (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Interior east elevation showing physical evidence of the location and dimensions of former 18th window opening after removal of modern plaster. (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Roof

Steeply pitched roof with lean-to addition on south side, covered with wood shingles.

Interior

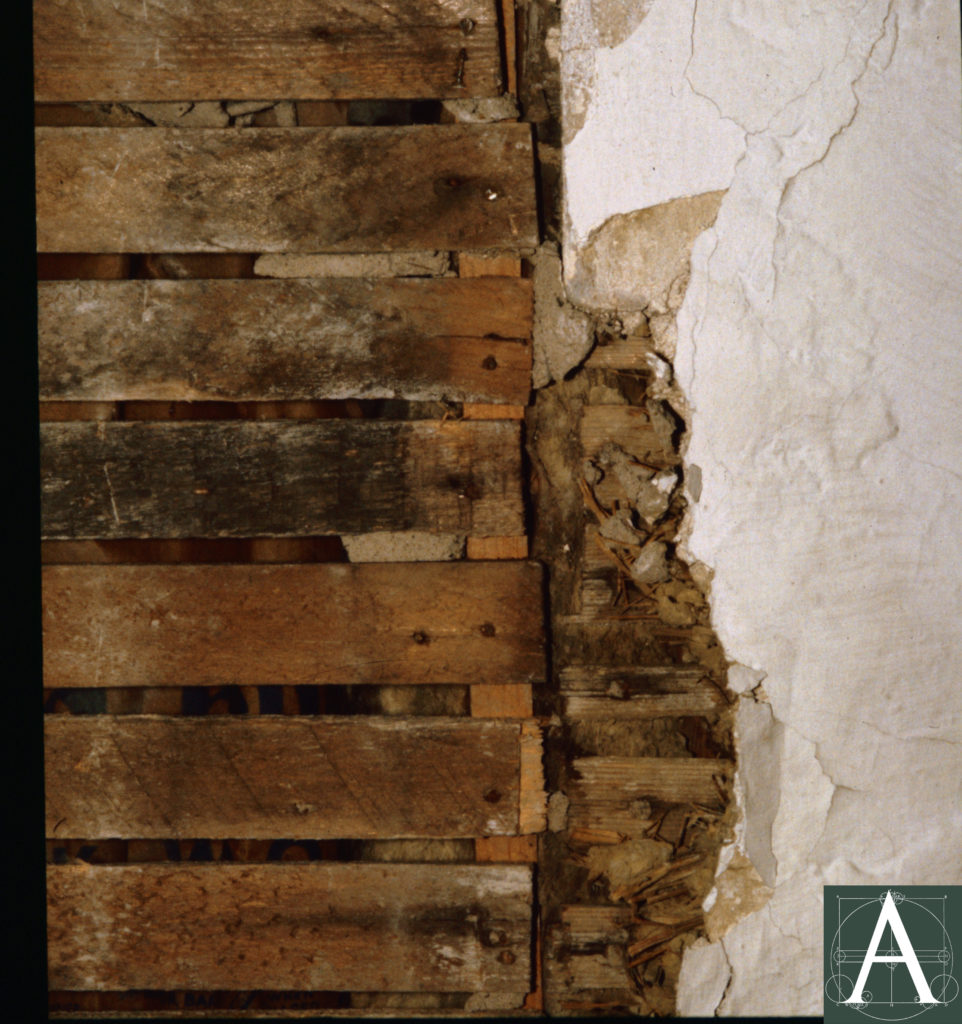

Interior east elevation showing plaster at the edge of former 18th century window opening with a base layer of clay and a finish layer of lime or modern gypsum (image courtesy of Historic New England)

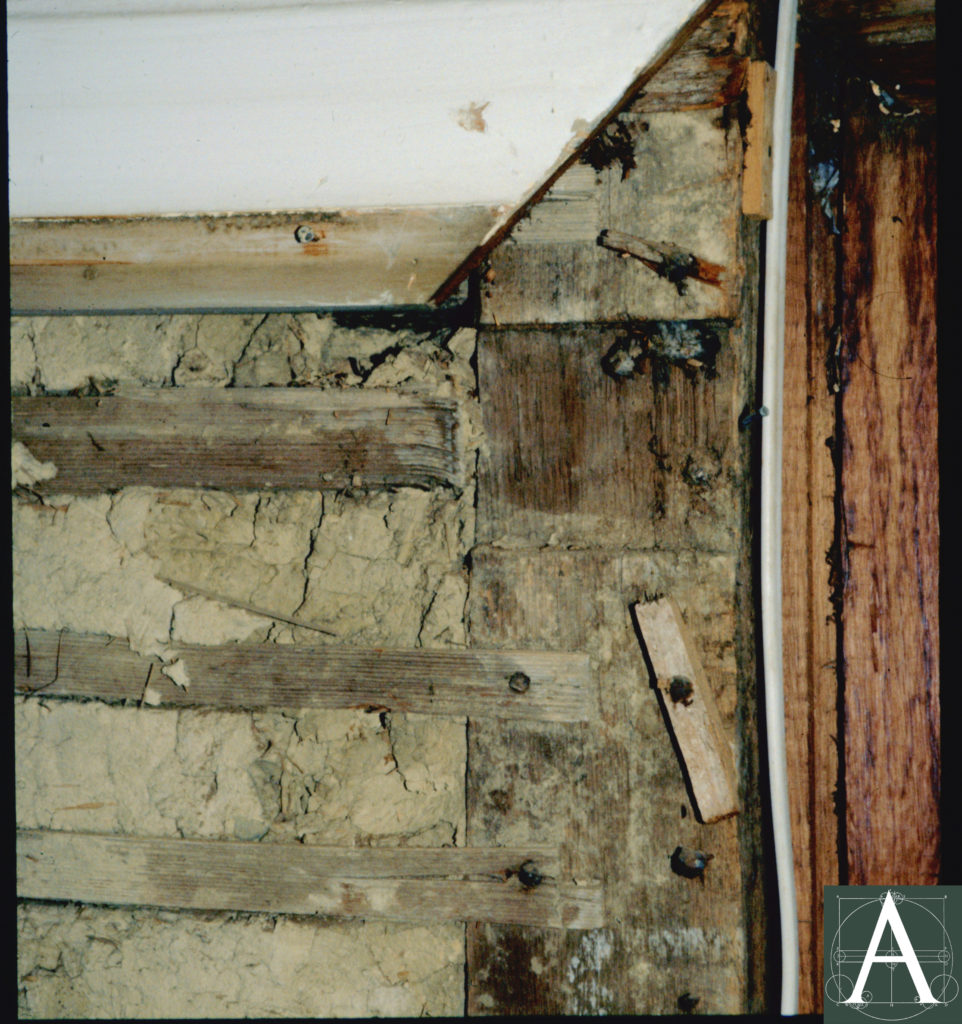

Interior east elevation showing riven lath originally covered with clay mortar and base layer of clay from bedding mortar of nogging (image courtesy of Historic New England)

Only the interior faces of the east and north walls of the building were examined in detail during the 1993 restoration of double-hung sash. As the 1943 casements were not based upon building-specific archaeological evidence and were deteriorated beyond repair, the decision was made to restore double-hung sash for which accurate evidence and information remained, thereby restoring the building to the appearance that it had for most of its existence. The locations of former double-hung sash openings were measured on the interior and were readily identifiable by the plaster with which they were patched. Modern plaster was carefully removed along with sawn lath which revealed the edges of old window openings. Wall finishes consisted of a base layer of clay-and-straw plaster applied to widely spaced riven lath set directly atop underlying clay mortar in which brick nogging was bedded between the wall studs. A thin layer of white plaster served as a skim coat over clay plaster. While the existing top layer may be a later addition containing gypsum, records of finish plaster of “clay well-struck with lime” exist as early as 1658. No chemical analysis of the finish plaster was conducted to confirm its composition, as this material was left in position.

The eastern portion of the house also retains former “cabins”, small rooms made by the installation of board partitions, or sometimes plaster walls, within large square rooms of First-Period houses. In this case, original rooms were subdivided into three spaces, namely, two “cabins” and a larger room containing the fireplace. These rooms have frequently been removed during restoration as later alterations; however, references to such rooms in early documents suggests that could have been original to some buildings or very early alterations. [Information needed.]

Contributor

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian, based upon physical examination in 1993.

Sources

Historic New England: unpublished “Architectural Evaluation of the William Howard House”. Abbott L. Cummings. (no date, probably ca. 1980)

Massachusetts Historical Commission: William Howard House MHC Inventory

Historic American Buildings Survey: Howard-Emerson House

Ipswich Historical Society: Ipswich Historical Society – William Howard House

Ipswich Historical Commission: http://www.historicipswich.org/emerson-howard-house-turkey-shore-rd/