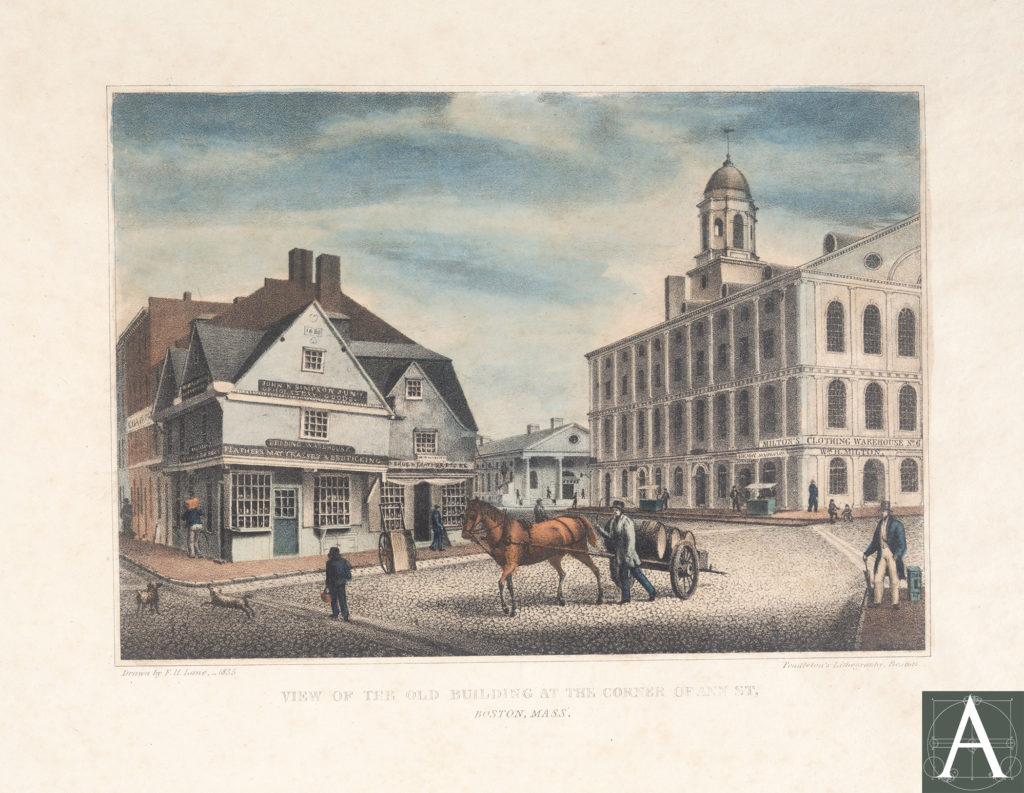

‘View of the old building at the corner of Ann St., Boston, Mass.” Lithograph from a drawing by Fitz Henry Lane showing Dock Square in 1835 with cobblestone paving, flagstone crosswalks, raised brick sidewalks, and short curbstones that match those in Nantucket’s Main Street Square. [Image courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum.]

Research into the history of pavement in New England towns and cities is hindered by the inconsistent manner in which streets were created. Many of the principal streets grew out of old paths and cartways, while many smaller streets were laid out privately and may have existed for many years before being accepted by local municipal governments. Records for the maintenance and paving of private streets are rare, especially those that were paved at the expense of abutters. After streets were accepted as municipal property, their paving and maintenance can sometimes be tracked through Town Meeting records, Selectmen/City Council records, and municipal financial records, but information exists largely in manuscript form stored separately in each community, presenting a daunting task for researchers.

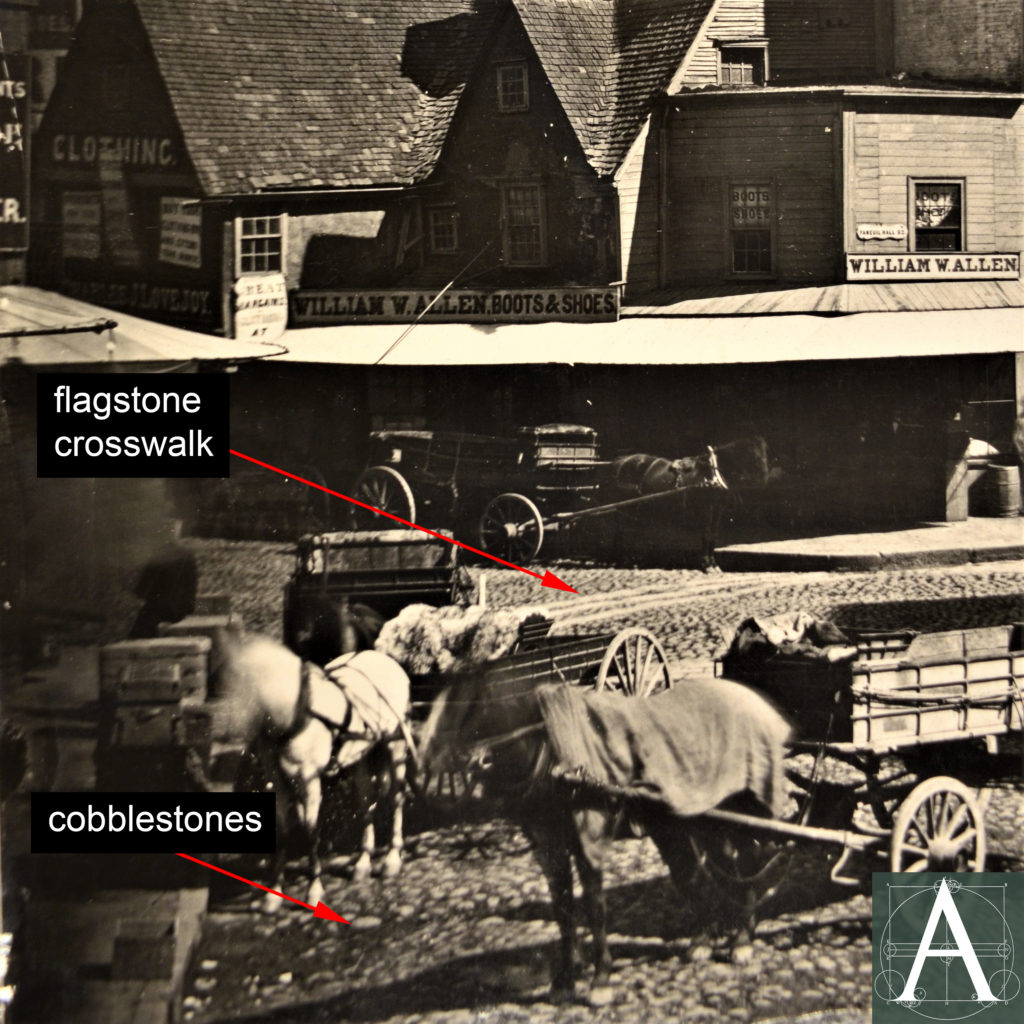

Cobblestone street paving with crosswalks of flagstone at Dock Square, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1860 [Image courtesy of Historic New England]

Introduction: Basic Early Paving Materials

Set in the ground with seasonal freeze-thaw cycles, exposed to weather in all seasons, and subject to vibration, pressure, and abrasion from traffic, pre-industrial paving materials tended to be stone or fired bricks, although wood boardwalks were used in some communities. Among the most common documented materials are:

Cobblestones: Naturally occurring, rounded stones are among the oldest paving materials and pre-date classical antiquity. In New England such stones were plentiful, having been deposited during the retreat of the last glaciation. In the Boston area:

These naturally rounded cobbles, averaging about seven inches in length, at first probably came mostly from nearby beaches, such as Cohasset, Nahant, and Cape Ann. Later, however, they were carried by coastal schooners from the Maine coast in large quantities. To make a pavement, they were set one against the other, in beds of sand, their long dimensions vertical. From time to time, more sand was added to fill the voids between the cobbles. (Kaye, 74-75.)

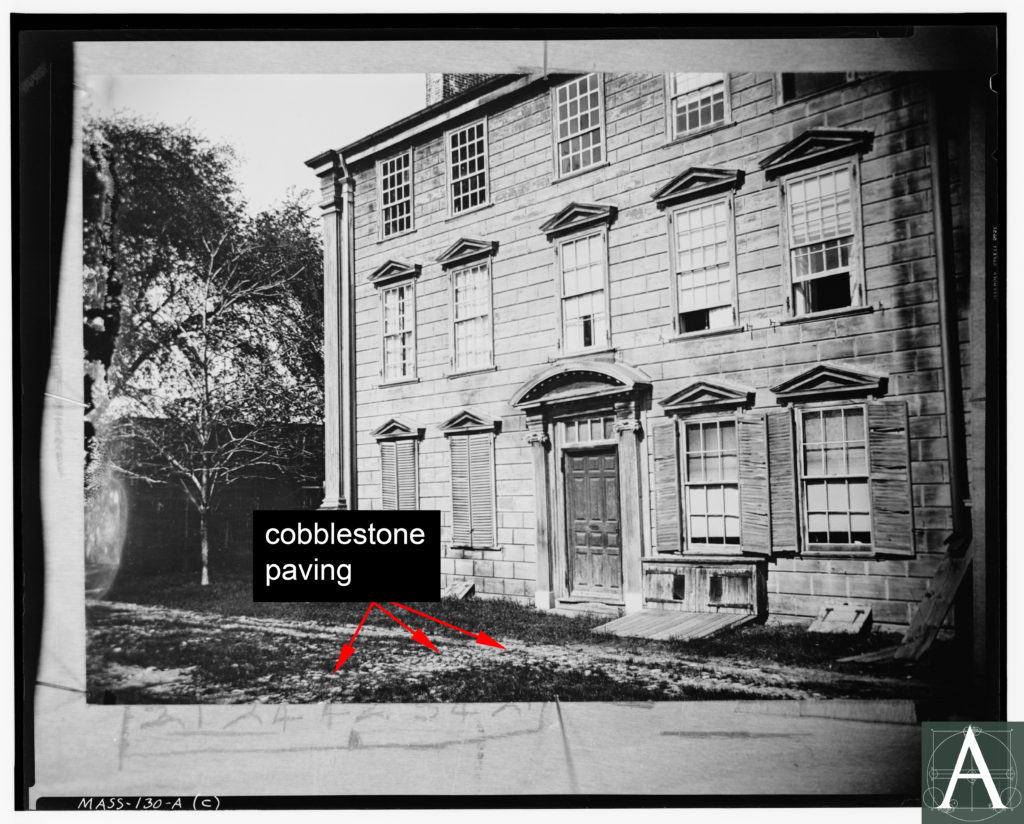

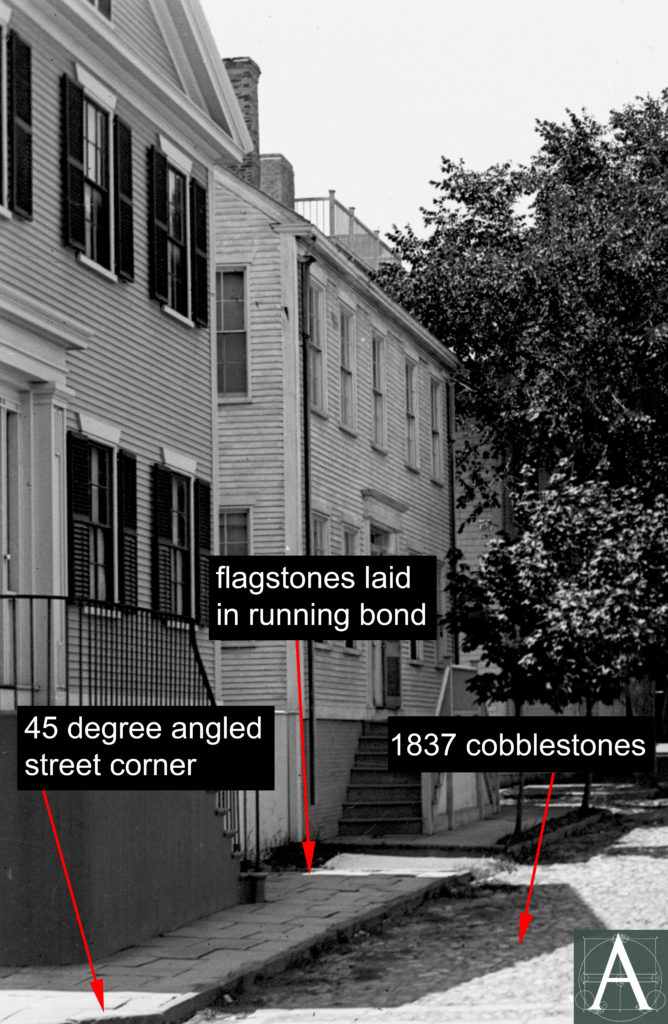

As early as 1663, John Josselyn (1608-1675) described Boston, saying most of the streets “are paved with pebbles” by which he meant cobbles. Near Boston in the 1730s at his country seat in Medford, Massachusetts, Isaac Royall paved the entry court to his imposing house with cobblestones; these were gradually overgrown with grass, but remain in place. Cobbles continued to be the most widespread paving material well into the nineteenth century and can be seen in drawings and photographs of such busy locations as Dock Square, Boston where cobbled street pavement, flagstone crosswalks, and raised curbs existed in 1835 when the area was drawn by Fitz Henry Lane. Similar paving was installed on Main Street Square, Nantucket, where it remains in position to the present. As late as the 1860s, cobblestones were still a viable paving material, when their installation or reinstallation in front of the Essex House in Salem, Massachusetts was documented by photographs in the collection of the Peabody-Essex Museum. Additional examples of cobbled paving that remain in place and bedded in the traditional manner can be seen in Boston at Acorn Street and Louisburg Square on Beacon Hill, and in Nantucket on many side streets.

Regional folklore frequently reports that these stones were imported from Europe as ballast on ships’ return voyages. Such a source of cobblestones is highly unlikely both because of the abundance of cobblestones along the New England coast and because of their low commercial value in relation to textiles, hardware, ceramics, and other high-value goods from Europe that were in demand among New Englanders.

Cobblestones partially overgrown with grass at the former garden entry court of the Usher-Royall House, 15 George Street, Medford, Massachusetts [Historic American Buildings Survey, Frank O. Branzetti, Photographer, June 4, 1940, copy of ca. 1890 view]

Cobblestone paving with a crowned center flanked by lower gutters to drain rainwater at Acorn Street, Boston, Massachusetts

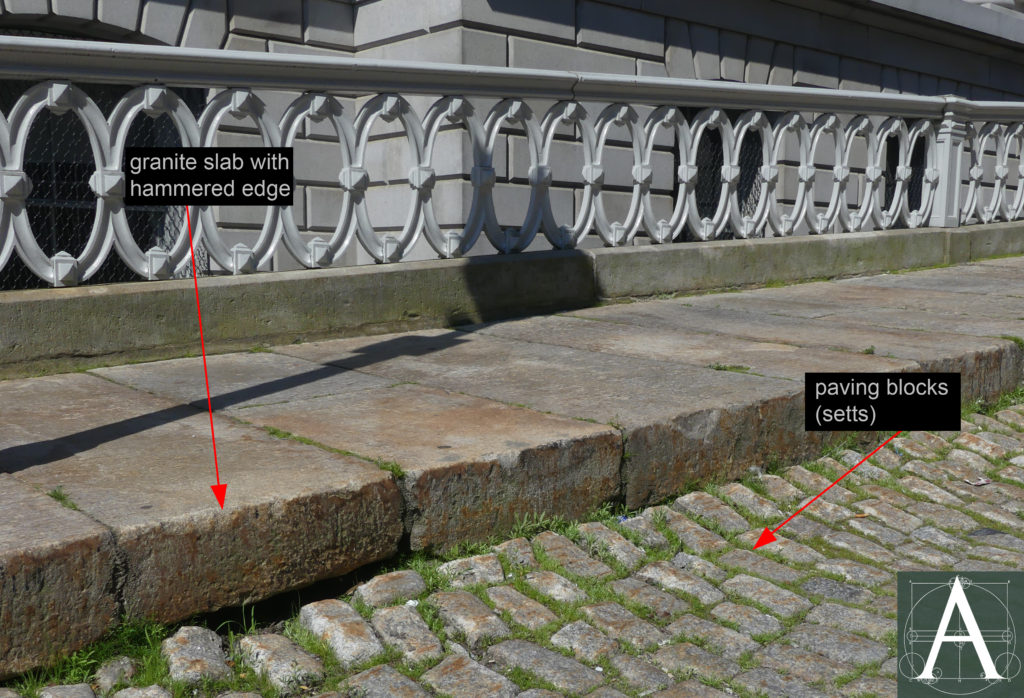

Paving Blocks, Paving Stones, Setts or Belgian Blocks: These squared paving stones came into use in the mid-nineteenth century as granite quarries began producing them in large numbers. Early setts were sometimes as large as one foot square. Examples of these early setts may survive in Boston in the crosswalks at both ends of Louisburg Square on Beacon Hill and in the gutter at the west side of the Square. Experience quickly led to a reduction in the size of setts to a range of 3-½ inches to 4-½ inches wide by 6 to 7inches in depth and 8 to 12 inches in length. Width was dictated by the need to provide sufficient variation in the paved surface that shod horses’ hooves could gain secure footing in the slight gap between stones, something that could not be achieved on the smooth surfaces of large flagstones.

As with cobblestones, regional folklore reports that many of these stones were brought from England and Europe. Industrial statistics from New England tell a different story. Initial production of paving blocks may have been carried out in Rockport, Massachusetts, but coastal quarries in Maine quickly became large producers. By 1889, the Commissioner of Industrial and Labor Statistics of Maine reported that 4,000 men were employed in the granite industry; of these, approximately 1,400 were granite cutters for architectural stones, while 1,000 were paving cutters. The value of paving-stone production rose throughout the nineteenth century but with slightly less speed after ca. 1895 when more easily installed macadam began to compete. Nonetheless, the production of paving stones continued to increase through 1921 (Dale, 440.) when it reached a peak and declined thereafter.

Granite paving blocks from New England were introduced into Boston in 1840 (Brayley, 168.); these may have been large blocks of Quincy granite (1’-6” x 14’) laid by Solomon Willard in front of the Tremont House Hotel although this date may be inaccurate as it post-dates the completion of the hotel by eleven years. The size of paving blocks decreased quickly in favor of smaller units. New England paving stones were reportedly introduced into Philadelphia in 1848 and New York City in 1850.

Laid on a sandy base and closely fitted, setts bore a slightly rounded top face, which provided an even surface that was important in an era before the widespread adoption of rubber tires or padding on wheels. Modern re-installations of paving stones have distorted public perception of this historic material by spacing the stones with wide gaps, bedding them in concrete, and exposing irregular split surfaces in an effort to create uneven surfaces that convey a perception of quaintness. Such installations would have been considered unacceptably rough by standards of the nineteenth century.

Gutter at the west side of Louisburg Square, Boston, Massachusetts, showing large setts (ca. 1835-45) with hammered granite curbing and brick sidewalk

Iron “Shells” or Blocks: Around 1850, a section of Court Street in Boston was paved with interlocking octagonal “shells” made of iron. These shells or blocks were 9 inches across and 5 inches deep with open centers of the shells that were filled with “broken stone concrete.” (Additional information needed)

Flagstones, also known as Flaggs: Sidewalks in Boston were paved with flagstones beginning with micaceous schist from Bolton, Connecticut, in the early nineteenth century. Although this stone, which became commercially available after 1809, was widely used in other cities, it was abandoned in Boston because it proved too soft for the volume of foot traffic or to the climate to which was exposed. It was followed by the use of North River flagstones (type of stone and quarry of origin not identified) and granite flagstones from Quincy and Rockport, Massachusetts as well as multiple quarries along the coast of Maine. (Brayley, 169.)

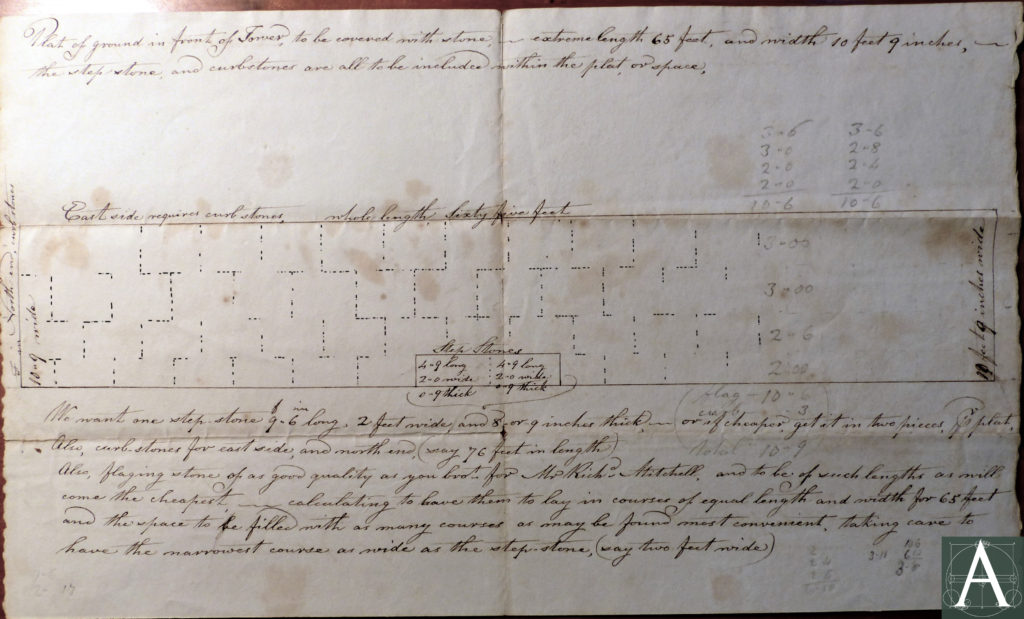

1831 sketch plan of flagstone paving to be laid in a running bond pattern together with brownstone steps at the entry to the Second Congregational (Unitarian) Meetinghouse at 11 Orange Street, Nantucket [Image courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association)

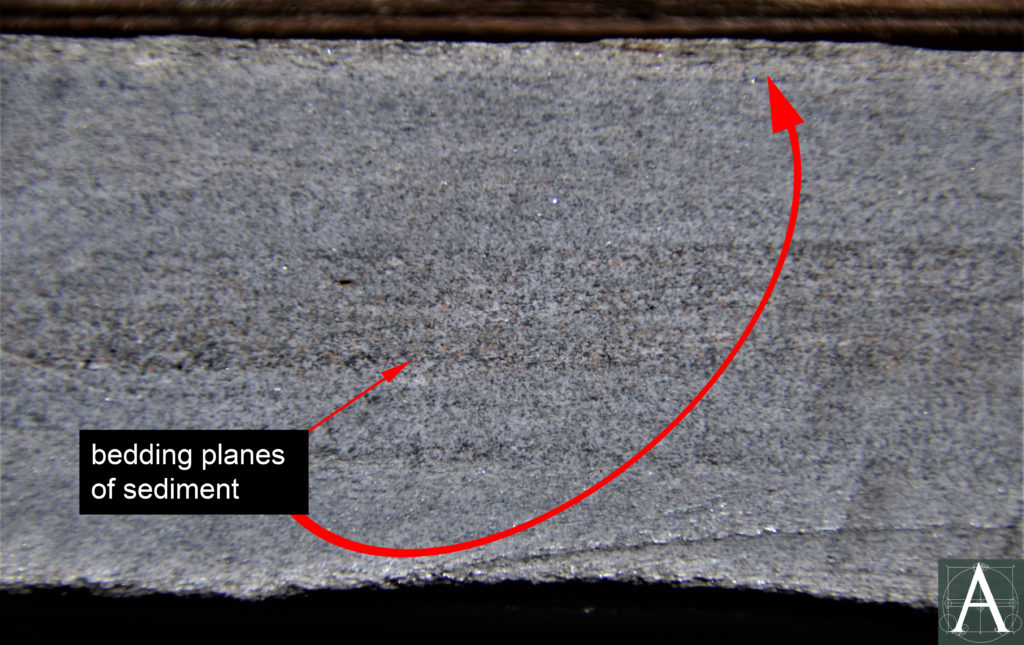

Section of schist used for sidewalk pavement in Nantucket, perhaps from Bolton, Connecticut, showing the bedding planes along which the stone could be split to provide flat walking surfaces

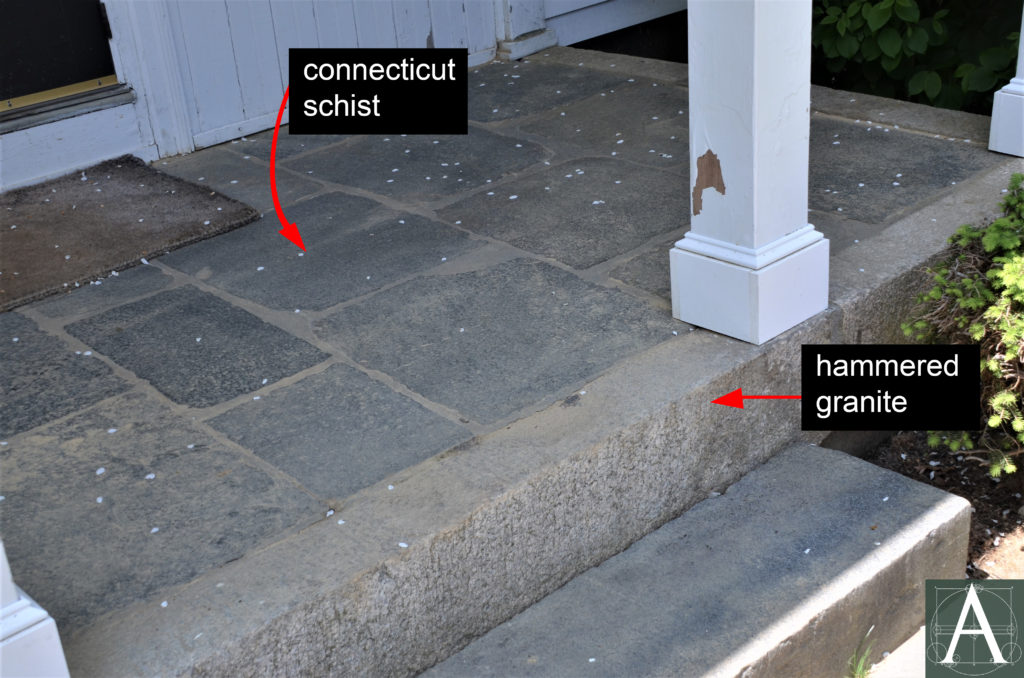

Entry portico at Thomas Swift House (1820), 207 Shore Road, Falmouth, Massachusetts, showing schist flagstones set in a floor framed by hammered granite curbing

Sidewalk paved with schist set in a running bond with granite curbstones and granite troughs running from downspouts to the street at the John Wendell Barrett House (1832-33), 72 Main Street, Nantucket, Massachusetts

Granite flagstones quarried in Maine became more frequent in the 1830s and 1840s. In 1840, T. & N. Fitzgerald of Nantucket advertised that they had “Just received from State of Maine 3000 lbs of first quality Coopers Flaggs, which will be sold on reasonable terms.” While installations using these granite flagstones have not been identified on Nantucket, large granite paving stones were widely used in the commercial districts of Boston, Massachusetts, and Portland, Maine, in the 1840s-1860s. [see Boston Case Study below] Examples can be seen at the State Street Block (1857) at 177-199 State Street, Boston and at the U.S. Custom House (1866) at 213 Fore Street, Portland.

U.S. Custom House, 312 Fore Street, Portland, Maine – built 1866-68, A. B. Mullet, Supervising Architect for the Department of the Treasury Department

Detail of the granite-slab sidewalk with hammered finish at the edges and paving stones bedded in sand/soil base, U.S. Custom House, Portland, Maine, built 1866-68

Bluestone sidewalks: In the second half of the nineteenth century, bluestone, came into use for sidewalks. While the term bluestone refers to sandstones of varying qualities and shades of blue/gray, in New England and New York, it generally refers to a dense sandstone, commonly called North River flagging stone. Produced predominantly in Ulster County, New York with the largest producers centered around Kingston, this stone is a “fine-grained compact sandstone, extremely hard and wearing upon a tool, and is made up of microscopic crystals of the sharpest sand” (Balch. The Great Bluestone Industry. 353). The name “North River” derives from the early name of the Hudson River. Commercial quarrying of this stone began between 1826-1838 and grew to become a major industry in the 1850s. By 1890, it was estimated that 20,000 men were employed in the quarrying, tooling, and shipping bluestone from quarries between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers with 7,000 of them employed in Kingston, New York. Stones ranged in size from thinner slabs (2” thick) that were known as “Corporation” flags and were cut to sizes of 4’ and 5’. Massive slabs could be as thick as 10” and seem to have commanded premium prices as vanity pieces. One bluestone slab measuring 15’ x 20’ x 10” (thick) was installed at the main entry of one of the Vanderbilt Mansions constructed in New York City on Fifth Avenue near Fiftieth Street in the 1880s. Prior to 1890 an even larger slab measuring 20’ x 24’ x 9” was quarried at Sawkill near Kingston, New York and moved to the shipping yard of Osterhoudt Brothers at Wilbur, New York in one piece to preserve its value which would have been reduced by 20% but cutting it (The Manufacturer and Builder. April, 1890. 80).

A large area of bluestone flagging (probably North River flagging stone which was recommended by the Mayor of Cambridge) survives on the north side of Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where it was installed in 1887 after considerable local debate about its cost and durability in comparison to brick. The sidewalk is composed of bluestone slabs that are 6 feet in length, 3 to 3-1/2 inches in thickness, and between 2 to 4½ feet in width, laid in a bed of packed sand.

Curbstones: As late at 1795, Eliza Susan Morton from New York (later the wife of Boston Mayor and President of Harvard College, Josiah Quincy III) was surprised while visiting Boston by the lack of brick sidewalks except on one section of Cornhill (present-day Washington Street):

The streets were paved with pebbles and, except when driven on one side by carts and carriages, everyone walked in the middle of the street, where the pavement was the smoothest. (Whitehill, 52.)

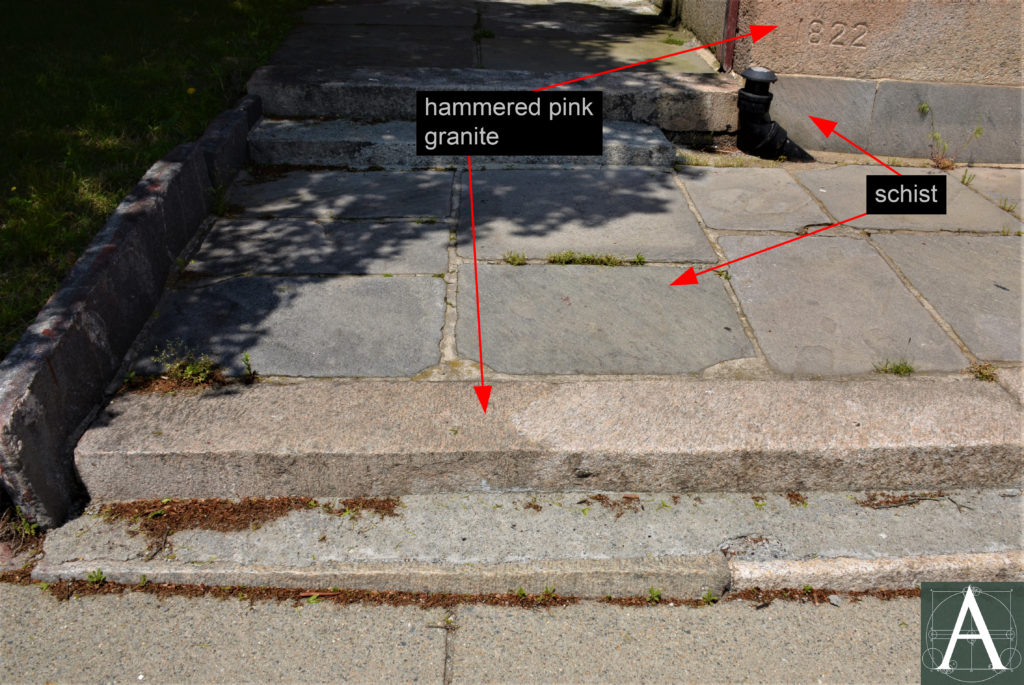

Curbstones became necessary once raised sidewalks became common to separate foot traffic from carts and carriages. An 1835 view of Dock Square and the Old Feather Store drawn by Fitz Henry Lane shows short lengths of curbstone separating a raised sidewalk from the cobbled street. The short lengths shown in historic views match many early curbstones in Nantucket that can be dated to the 1830s from construction documents and from their retention of flat-wedge marks that were left by a method of quarrying that passed out of use in the 1830s. (Garvin, 44-45.) Made of schist, these curbstones match those set at the edge of the entry to the Quaker Meeting House of 1822 in New Bedford, which suggests a shared source, perhaps in Connecticut. With widths of only 2¼ to 3 inches and lengths of 2-4 feet, these curbstones are narrower and shorter than modern curbstones which are often 5 to 6 inches wide and 6 to 8 feet in length, rising to 10 to12 feet in length by the twentieth century.

Schist curbstone at 5 Liberty Street, Nantucket, Massachusetts, bearing flat wedge marks from quarrying by a method that passed out of use in the 1830s.

Construction accounts for the Henry Coffin House of 1834 at 75 Main Street, Nantucket record that Seth Bryant was paid $50.81 for “hamering Stone curb, steps &c.” By comparison, Abner True was sent from the Hopewell Quarry in Sullivan, Maine, to work on site hammering the house’s 29 window lintels and sills for which he was paid $28.00 for 42 days’ work, slightly more than half the cost of hammering curbstones and steps. Large numbers of hammered granite curbstones remain in position on Boston’s Beacon Hill, especially at Louisburg Square which was developed with large, expensive houses between 1834 and the 1840s. [see Boston Case Study below].

With the rapid expansion of granite quarries in New England after the 1840s, granite became the predominant material used for curbstones. Curbstone sizes appear not to have been standardized until the twentieth century and the wide variety of granites found throughout the region reflects the large number of quarries that produced them – 31 by 1923. (Dale, 430-431.)

Wood: Wooden Paving Blocks & Boardwalks: Although less durable than stone, wooden blocks were used for paving streets in locations where sound-dampening was desired. In August, 1840, Nantucket’s Town Meeting voted to repave a section of Center Street near the commercial center of the town, offering to abutters the opportunity to substitute wooden paving for stone upon the condition that the abutters pay the difference in cost between the two materials. Although rare, some wood paving in the shape of bricks laid in a staggered bond survived as late as the 1970s on Cedar Lane Way at its north junction with Mt. Vernon Street on Boston’s Beacon Hill. Examples may survive elsewhere or in other communities. [Additional information needed]

Even less durable than wooden paving blocks, wooden boardwalks existed in some locations into the late nineteenth century, and perhaps even into the twentieth century. Until the mid-1830s, the street plan of Provincetown, Massachusetts, reflected the town’s dependence upon fisheries. Houses were strung along the waterfront which they faced. Unpaved lanes led inland from landings, and the broad sand flats exposed at low tide served as a roadway to haul goods up and down the length of the town. In 1835, the Barnstable County Commissioners laid out Front Street (present-day Commercial Street) set back from and parallel to the water line, using portions of an existing footpath. Eventually buildings on the south side of the new street were re-oriented northward to the increasingly important street traffic rather than the water. The sandy soil that served as the street’s surface may have impeded pedestrian traffic and led the town to use its share of the Federal Surplus from the Jackson Administration to build a wood-plank sidewalk on the street’s north side in 1838. (Provincetown NRHP Nomination, Section 7, p. 3.) Even in larger towns and cities, such as Cambridge, Massachusetts, boardwalks were installed as sidewalks at least as late as the mid-1880s. Reverend William Lawrence of Episcopal Theological Seminary on Brattle Street lamented the injustice that the school should be forced to pay an assessment for a brick or stone sidewalk in 1887 “after they had paid so large a proportion of the present board walk within a few years.” (Cambridge Chronicle, April 9, 1887.) [see Cambridge Case Study below] In Brookline, Massachusetts, boardwalks remained in use as late as the 1950s.

Bricks: Brick paving forms the largest proportion of surviving historic paving for sidewalks throughout the region. Although it existed on a short length of Washington Street in Boston as early as 1795, its widespread use appears to post-date the 1830s-1840s when brick production grew rapidly and industrialization of brick-making created more uniformly fired, harder, and more durable brick than had been previously available. Costing roughly half as much as flagstone to purchase and install, bricks were perceived by many to provide a more even and durable surface than could be created with flagstone. As with other paving materials of the period, bricks were generally installed on a bed of sand or “dirty sand,” i.e., sand with a small proportion of impurities, such as clay that helped it hold together, but not enough of these impurities to stop the absorption of rainwater back into the ground through the joints.

The extent to which brick was also used for street paving is not well documented. [Additional information needed.] On Nantucket, a section of Main Street was paved with vitrified brick in 1902, but the practice was not continued for other streets, perhaps because of its cost or the higher level of noise created by shod hooves and metal on the brick surfaces.

Case Studies

The following case studies contain documentation submitted by contributors on selected topics for which they have prepared documentation. More examples are needed to understand the materials and patterns of paving in New England, and to identify those rare surviving examples of pre-twentieth century paving. If you have documentation, please let us know either by making a submission or by sending a message to the editor.

Case Study: Nantucket, Massachusetts

In the 1830s-1840s, at the height of its prosperity, Nantucket embarked on a steady program of paving streets and sidewalks in the center of the town. A high proportion of paving installed at this time, as well as some that preceded it, remains intact to the present. Prior to 1830, some sidewalks, and perhaps sections of streets, had been paved by the owners of abutting houses. Existing paving was mentioned tangentially in the Town Meeting records of 1830 when a section of Main Street was ordered to be paved from the corner of Fair Street to a point “seven feet from Hezekiah Swain’s wall” where it was “to Join the Curbstone of the Flagings on the north side…” (Nantucket General Accounts. 1826-1837, September 16, 1830, no page number.) Another section of existing flagstone paving may be inferred by an order for stone made on December 13, 1830 for paving in front of the Second Congregational (Unitarian) Meetinghouse. Paul West ordered from Captain Timothy Fitzgerald, “an additional quantity of flagging stone of the same kind as you brought for the South Tower before.” The stone was to pave two separate areas, one 17 feet by 10 feet, the other 14 feet by 8 feet. It seems likely that this stone was intended to supplement existing paving in front of the meetinghouse. The order may have been supplanted in 1831 with a larger order to repave the entire area uniformly as sketched on the later order. [see illustration Flagstones above] The extent of pre-1830 paving in the core of Nantucket has not been fully documented.

The impetus for a more comprehensive plan of paving arose in the mid-1830s from the expense and inconvenience of maintaining the town’s sandy streets. In 1835, a committee appointed by the Selectmen to consider the condition of the streets reported:

It is well known that the Streets within the Town are generally inferior, some of them very bad, perhaps more than they are in any other place of Equal Consequence for population, and Commercial importance good roads are of the First Necessity…..the Committee think the time has come for the Town to take some decided and Determinate Step to improve the Streets within Compact part of the Town…..that patching, sand carting, and temporary Systim [sic.] be wholly discontinued…and that a regular plan of Permanent improvement Should now be recommended by grading, Curbing and paving the Streets according to the most approved method now in use… (Nantucket General Accounts 1826-1937, 173-174.)

The committee further recommended that the Town authorize borrowing up to $10,000 to start the work. Implementation began in 1836 with the expenditure of $7,108.12 by the Surveyors of Highways who reported that the following streets were paved:

- Gardners street from Gideon Folgers by the head of Liberty Street;

- Paved and Curbed South Water Street from Main Street to the head of New North Wharf;

- Paved and Curbed Pearl Street [modern India Street] from its head at Liberty Street to the Dock;

- Paved and Curbed Orange Street from Main Street to Martin’s Lane;

- Paved and Curbed Main Street from Federal Street to Waters edge, head of Streight [sic.] wharf;

- And in addition to the above have paved the Ends of the different Streets where they intersect with the above naimed [sic.] ones; in order to preserve and keep in order the water Courses. (Nantucket General Accounts 1826-1937, 191-192.)

The financial accounting that accompanied this report primarily records the extensive labor needed to accomplish this work with horses and men as the primary source of motive power. These accounts are interspersed with un-itemized payments to individuals. A few of these payments contain the notation “for a load of stones”; however, the small charges that accompany these notations suggest that the stones may have been gravel or other materials for the road’s base. Payment #59 of 1836 for $41.44 was made in October, 1836 to T & N Fitzgerald – Timothy and Nathaniel Fitzgerald who provided flagstone and other construction stone to Henry Coffin in 1833-1834 for the construction of his house and the paving of his sidewalk at 75 Main Street. This charge may have included paving stone.

Sidewalk and curbstone of schist installed 1833 & 1836, as they existed ca. 1890 at 86 Main Street, Nantucket, Massachusetts [Image courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association – GPN4155]

Main Street Square, Nantucket, Massachusetts, 1916 showing cobblestone streets and flagstone crosswalks re-set in 1846 following the Great Fire of 1846 when Main Street was widened to form Main Street Square [Courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association – F345.]

In the early twentieth century, the town experimented with tarring and concreting streets, although it was not until 1918 when the ban on automobiles was lifted and cars first appeared on the island. The installation of new sewer lines on Main Street in 1919 and automobile traffic led to a proposal to pave Main Street and Main Street Square with concrete. Summer residents and the Civic League rose in opposition to this change and prevailed in retaining the original cobblestone paving by raising money privately for its repair. The debate continued well into the 1920s as additional water and sewer installations left the cobblestone paving in poor condition. Finally, in 1931, Frank Gifford, president of the water company, sought to solve the problem by making a commitment to repair the streets by traditional methods after the installation of new water lines. Antone F. Sylvia, a local mason from the John C. Ring Company, was trained to lay cobbles and flagstones after which he and others whom he trained maintained the cobbled streets until 1972 when the last of his trainees died before he could train a successor. Since the 1970s, repair has been inconsistent with the result that historic pavement has fallen into greater disrepair and is once again endangered by reconstruction with modern concrete or asphalt bases to meet national road-building standards that do not fit the historic character or needs of the island, and that would fundamentally change their appearance and the way in which they function. As of this writing in June 2019, the future of these unique pavings is uncertain.

Case Study: Boston, Massachusetts

As the region’s largest city, Boston was also probably the first to have pavement on its streets and it possessed the region’s largest network of paved streets in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. Historic photographs and lithographic views show paving substantially like that seen in Nantucket, namely cobbled streets, hammered granite curbstones, and flagstone and brick sidewalks until the second half of the century when paving stones (setts) replaced cobblestones in most locations. Two of the city’s best-preserved examples of early paving exist on Beacon Hill at Louisburg Square and Acorn Street, the former having been developed primarily in the mid-1830s-1840s as expensive upper-class housing, and the latter having been developed in 1828 as more modest houses on a narrow lane.

Louisburg Square was originally part of a larger tract of 18.5 acres of pasture land purchased in 1796 from the painter John Singleton Copley (1738-1815) by the Mount Vernon Proprietors. Initially intended as a neighborhood of substantial free-standing houses, Beacon Hill quickly became a densely built neighborhood of imposing brick row houses. By the 1820s, development had filled all of the south and east portions of the original tract, leaving undeveloped only the land that would become Louisburg Square then in the possession of four of the Mount Vernon Proprietors, namely, Harrison Gray Otis, Jonathan Mason, Benjamin Joy, and William Sullivan. By 1826, the four investors laid out, and conveyed to themselves individually, twenty-eight lots for row houses on the east and west sides of a narrow park flanked by two roads and on Pinckney Street at the north end of the park. To assure that the area would be developed with fine houses in keeping with the rest of Beacon Hill, deeds to the lots stipulated that only houses of brick or stone could be built on the lots, that buyers of the lots would share the cost of building party walls with adjacent property owners, and that each house would be permitted “an arch” at the basement to provide access to rear yards, as no rear alleys were created by the plan.

Construction of houses did not begin until 1834 and was nearly complete by 1844 when property owners entered into an indenture to form the “Proprietors of Louisburgh Square.” This indenture confirmed the previous restrictions on the types of buildings that could be built, and it provided for enlarging the central park by adding four feet on each side (east and west) and five feet to each end (north and south) before fencing was installed. Annual meeting minutes do not record when the streets and sidewalks were paved. It seems likely that some paving was installed in the 1830s, but its layout reflects changes made to the park in the mid-1840s.

Although the original investors and the Proprietors of Louisburg Square recorded an intention to give the streets to the City of Boston whenever the City might be willing to accept them, the Proprietors consistently declined to pursue such a transfer. Beginning in the 1850s, they began a periodic practice of closing the roadbeds for a day after which they recorded the closure notices at the Registry of Deeds together with attestation that the closure was not challenged to protect themselves from any public claim of right of passage by common use or adverse possession. The last proposal to convey the road beds to the City of Boston was made at the annual meeting of 1901. The motion failed to be seconded, and the question was concluded without a vote.

Private ownership of the roadbeds and sidewalks has preserved a remarkable range of early paving materials. Crosswalks at the north and south ends of the Square are laid with medium-sized granite pavers that may have been among the early oversized pavers made in the 1830s before smaller sizes became standard. The gutters of upper roadway (east) are cobbled, as were the areas at the north and south ends of the park, while the gutters on the lower roadway (west) are paved with oversized paving blocks like those in the crosswalks. The travel lanes on the east and west roadways were paved with packed dirt and gravel that was sprinkled with water in the summer to reduce dust arising from traffic. Gravel roadbeds were probably covered with asphalt in the 1920s when the Proprietors made a proposal that was refused by the City of Boston to use its paving contractors. Subsequent repairs and re-paving of the roadbeds by private contractors are recorded in 1925 & 1928. Curbstones on both the upper and lower roadways as well as the sidewalk surrounding the park bear both the distinctive chisel marks of hammered granite and incised letters or Roman numerals “V” near the mid-points of many of the curbstones, especially on the sidewalk at the west side of the Square. Some houses on the west side of the Square also retain coal chutes set in hammered granite surrounds at their front sidewalks. Brick sidewalks seem likely to be an original feature, as they appear in all historic photographs of the area.

Maintenance costs of the original paving appear to have been low compared to other costs incurred by the Proprietors. In 1844, the Proprietors agreed to install an iron fence around the park at a cost that required an assessment of $150.00 per house. After this major expense, the property owners assessed themselves $5.00 per year most years to cover the cost of maintenance of the park, cleaning the streets and sidewalks, and minor repairs. That figure alternated between $5.00 and $10.00 per year in most years between 1865 and 1880, and $10.00 per year in most years between 1880 and 1920. While maintenance of the cast-iron fence was an on-going drain on money, relatively few large expenses were incurred for the road and sidewalks. In 1870-71, a special assessment of $35.00 was levied “to meet the expense incurred for repairs and painting the fence, paving gutters, gravel & c.” In 1877, changes to the grade level on the lower (west) roadway were undertaken at a total cost of $200.00, presumably to improve the drainage of rainwater run-off. In 1877, the question of “watering roadways of the Square” was referred to a committee. The Proprietors’ inability to get permission to use water from the public water supply for this purpose led them to consider drilling a well in the Square for this water. It is not clear if the well was ever drilled, as payments of $150.00 per year for sprinkling the roadbeds with water appear in annual meeting minutes after 1885 and continued to be a source of discussion through at least 1907 when the annual meeting urged a committee “to look into a more permanent method of reducing dust on the road beds.”. The largest project recorded for road maintenance came in 1898 when roadbeds were rebuilt by Brookline Gas Co. without cost to the Proprietors, presumably to repair damage done by the installation or replacement of underground gas pipes. Detailed vouchers (receipts) and correspondence were mostly discarded in 1911 after the Proprietors voted to allow the clerk to discard such records, leaving only the minutes of the annual meetings and summary ledgers that describe repairs in general.

Original pavement at the south end of Louisburg Square, Boston, Massachusetts – crosswalk may be partially paved with early, oversized sets (1830s) that have been incised with grooves to reduce slipperiness of their surfaces.

View of the north end of Louisburg Square ca. 1890-1910 showing original paving consisting of a cobblestone road bed, granite curbstones, and granite paving stones at the crosswalks. [Image courtesy of Historic New England – reference code: PC001.02.01.USMA.0340.5390.001]

Current view of the north end of Louisburg Square showing original sidewalks, curbstones, crosswalks and cobblestones.

Incised “V” found in hammered granite curbstones (1830s) on the west side of Louisburg Square, Boston, Massachusetts – purpose unknown [information needed]

Coal chute on the west side of Louisburg Square, Boston, Massachusetts – granite edgings bear parallel grooves from hand-hammered finishing

Located one block south of Louisburg Square, Acorn Street was developed in 1828 with modest brick row houses on the south side of a narrow lane facing the rear yards and outbuildings of more ambitious row houses on Mt. Vernon Street facing Louisburg Square. The street seems likely to have been paved with cobblestones from the outset, and additional details such as granite troughs to drain rainwater from downspouts to the gutter correspond to details found in surviving paving of the same period on Nantucket. Several of the hammered granite curbstones bear masons’ or quarrymen’s marks consisting of incised Greek crosses and the letter or Roman numeral “V.” Records of the paving and maintenance of Acorn Street may remain in the City of Boston’s financial records.

Granite channel and cut in curbstone (1828-1830s) to drain downspout – Acorn Street, Boston, Massachusetts

Masons channel and cut in curbstone (1828-30s) to drain downspout – Acorn Street, Boston, Massachusetts

Quarried granite blocks:

Elsewhere in Boston, sidewalk paving in the form of large quarried granite blocks survives in front of mid-nineteenth-century buildings in the commercial district and in front of the massive granite warehouses built along the waterfront, such as the State Street Block (1857 – 177-199 State Street) and the Mercantile Wharf (1855 – Atlantic Avenue). Less common in residential districts, paving of this type was used for a small number of residences of which the Thayer Mansions (1847 – 70-72 Mt. Vernon Street) are among the most notable for their large scale and design by Richard Upjohn, architect.

Quarried granite paver with grooved surface (1847) installed in front of the Thayer Mansions at 70-72 Mt. Vernon Street, Boston, Massachusetts

Quarried granite pavers with grooved surfaces set in a herringbone pattern at the Mercantile Wharf (1855) at 71-111 Atlantic Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts

Case Study: Cambridge, Massachusetts

Far less populous than its neighbor, Boston, Cambridge was slower to pave its streets and sidewalks. In the early nineteenth century, several turnpikes were cut through the town to provide direct routes to Boston and neighboring towns. In 1821, these roads were described by an observer:

…..Next to Craigie’s [contemporary Cambridge Street] the one most used is that through Cambridge Port [contemporary Massachusetts Avenue], but some part of this road is soft and muddy after rain, and in the dry season so dusty, as to make traveling very unpleasant. The Concord Turnpike [contemporary Broadway] is sandy and often out of repair… (Maycock & Sullivan, 38.)

During the same period, William Wells, a schoolmaster, described Brattle Street, which had been the principal road westward to Watertown since the seventeenth century, as “a mere lane, with neither pavement nor sidewalk, and the great part of the year a continuous quagmire, with no means of communication with the outside world except by a two-horse stage coach twice a day.” (Maycock & Sullivan, 46-47.)

By the second half of the nineteenth century, suburban development reached out along Brattle Street with the construction of large-scale expensive houses between the widely spaced country seats that had been constructed on the street’s north side in the previous century. By the 1880s a boardwalk had been built along the street’s north side, but new residents considered it inadequate and proposed to the City that a paved sidewalk be built in its place. A lively debate followed with the Board of Aldermen proposing to pave with brick, while residents expressed both a strong preference for flagstone and concern about the potential damage that would be done to the street’s trees by excavating to create a level base for paving. On April 23, 1887, the Mayor wrote to the Board of Aldermen to review the situation and to side with residents, saying, “In my opinion a pavement of North River flagging stone of not less than five feet in width, two and one-half inches thickness, in every way makes a better and more desirable sidewalk than one of brick.” (Cambridge Chronicle, April 30, 1887.) Cost was a consideration, as flagstones cost twice as much as bricks. Abutters had agreed to pay the cost of flagstones, but the Aldermen sought additional assurance that the abutters would pay an additional assessment to replace the material if it wore out. In attempting to point out the unfairness of this demand, the Mayor speculated that “if the flagging should last twenty years (the usual life of a brick walk) and then need to be replaced, the city by ordering to be laid a walk of brick or of flagging of different width, either wider or narrower than the original walk, could reassess abutting estates. Such a discrimination against flagging is unfair.” (Cambridge Chronicle, April 30, 1887.)

In the end, flagstone pavement was installed along most of the street with abutters bearing the cost of bluestone. Pavers measuring 6 feet in length, 3 to 3½ inches in thickness, and between 2 to 4½ feet wide were installed in July, 1887 to create a six-foot-wide path. On December 3, 1887, The Cambridge Chronicle noted that “the space on either side of the flagging stones…has been nicely sodded, adding greatly to the appearance of the sidewalk.” Despite the initial speculation that the useful life of the flagstones might be twenty years, they remain in position bedded on sand and soil to the present – 2019.

Case Study: New Bedford, Massachusetts

Public records note the laying out and opening of “highways” in North Water Street, the easterly section of Middle Street, and North Second Street as early as 1788, but remain silent on whether they were paved or merely packed earth. In 1830, Town Meeting fixed the boundaries of streets and roads installing granite monuments level with the ground at the centers of intersections to mark boundaries. At the same time the Town published a list of all accepted streets and the dates on which they were accepted as public property. Sixty listings recorded various sections of thirty-one streets accepted between 1769 and 1830 but made no reference to road surfaces or sidewalks. In 1832, the town began building fire reservoirs (presumably vaults beneath the streets in densely built portions of the town) and installed the first flagged sidewalks. In 1838, “a short section of South Water street was paved, as an experiment to test the method of improving highways. It was successful and was approved by the citizens.” Paving continued into 1839, although the materials used for paving were not cited. Local records report:

Possibly the first mention of macadam used in the city is here when the Bridge Square formed by a continuation of Front Street, It was macadamized, and the cost including curbing and crossings was $1,107.00. (Whaling City: New Bedford Website.)

Closer examination of Town Meeting and City records is likely to produce more detailed information about paving materials and the sequence in which they were used as well as their sources.

Connecticut (?) schist flagstones set in hammered pink granite steps at the Friends Meetinghouse (1822) at 83 Spring Street, New Bedford, Massachusetts

Contributors:

Hillary Rayport Hedges

Charles Sullivan

Brian Pfeiffer, architectural historian

June 2019

Sources:

Brayley, Arthur W. History of the Granite Industry in New England. Boston: Published by the authority of the National Association of Granite Industries of the United States, 1913. Volume 1. https://archive.org/details/historygranitei01braygoog/page/n12

Dale, T. Nelson. The Commercial Granites of New England. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1923. https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/0738/report.pdf

de Pold, Hans. The Quarryville Boom Town. Bolton Historical Society, 2001. http://www.boltoncthistory.org/quarryville.html

Garvin, James. A Building History of Northern New England. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2001.

Goodman, Phebe. The Garden Squares of Boston. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2003.

Goudie, ‘VB’ Doug. ACK in Ashes: Nantucket’s Great Fire of 1846. 2016: Published by author.

Ingram, Henry Balch. The Great Bluestone Industry. Popular Science Monthly, v. 45, July 1894. 353-357. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_45/July_1894/The_Great_Bluestone_Industry

Kaye, Clifford A. “The Geology and Early History of the Boston Area of Massachusetts, a Bicentennial Approach.” Geological Survey Bulletin 1476. United States Geological Survey. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976. https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1476/report.pdf

Maycock, Susan and Sullivan, Charles. Building Old Cambridge: Architecture and Development. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

Pieper, Richard. The Granite Streets and Sidewalks of Lower Manhattan. APT Bulletin, 50: 2-3, 2019. 5-13.

Whitehill, Walter Muir. A Topographical History of Boston. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1968.

Town of Nantucket. Office of the Town Clerk. Town Records: 1826-1837; 1829-1834; 1834-1838; and 1838-1840 (manuscript).

American Journeys: John Josselyn, document AJ-107. http://www.americanjourneys.org/aj-107/summary/

Historic American Buildings Survey. Isaac Royall House, Medford, Massachusetts. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ma0489/

Bluestone Sidewalks. The Manufacturer and Builder, April, 1890. 80-81. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924080795275&view=1up&seq=87&size=125

Muddy River Musings: The Long History of Wooden Sidewalks in Brookline. August 28, 2018. http://brooklinehistory.blogspot.com/2018/08/the-long-history-of-wooden-sidewalks-in.html

National Park Service: National Register of Historic Places Nomination – Fitch Bluestone Company Office – https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/16000256.pdf.

Provincetown Historic District National Register of Historic Places Nomination, Provincetown, Massachusetts. http://mhc-macris.net/Details.aspx?MhcId=PRO.A

Rock-Solid Industry in 19th-Century Bolton. Connecticut History.org, 2019. https://connecticuthistory.org/rock-solid-industry-in-19th-century-bolton/

“View of the old building at the corner of Ann St., Boston, Mass.” Milton, William H., proprietor. Simpson, John K., Jr., proprietor. Pendleton’s Lithography, lithographer. 1835 [Boston Athenaeum call number A B64B6 Sh.ol.1835]

Whaling City: New Bedford – Chronology of New Bedford History by Year. http://www.whalingcity.net/new_bedford_local_history_1779_1799.html

Wikipedia: John Singleton Copley. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Singleton_Copley

Wikipedia: Fitz Henry Lane. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fitz_Henry_Lane

Wikipedia: State Street Block. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_Street_Block_(Boston)

Wikipedia: Tremont House. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tremont_House_(Boston)

Wikipedia: United States Custom House, Portland, Maine. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Custom_House_(Portland,_Maine)